How department stores changed the way we shop

- Published

"No, I'm just looking." Words most of us have said when approached politely by a sales assistant while browsing in a shop. Most of us will not have then experienced the sales assistant snarling: "Then 'op it, mate!"

Hearing those words in a London shop made quite an impression on Harry Gordon Selfridge.

The year was 1888, and the flamboyant American was touring the great department stores of Europe - in Vienna, Berlin, the famous Bon Marche in Paris and then Manchester and London - to see what tips he could pick up for his then-employer, Chicago's Marshall Field.

Field popularised the phrase "the customer is always right". Evidently, not yet the case in England.

Two decades later, Selfridge was back in London, opening his eponymous department store on Oxford Street - now a global destination for retail, then an unfashionable backwater, but handily near a station on a newly opened Tube line.

Selfridges - pictured on its opening day, 15 March 1909 - became renowned for sumptuous window displays

Selfridges caused a sensation, partly due to its sheer size: the retail space covered six acres (24,000 sq m).

Attitude

Selfridge also installed the largest glass windows in the world - and created, behind them, the most sumptuous shop displays.

But more than scale, what set Selfridges apart was attitude.

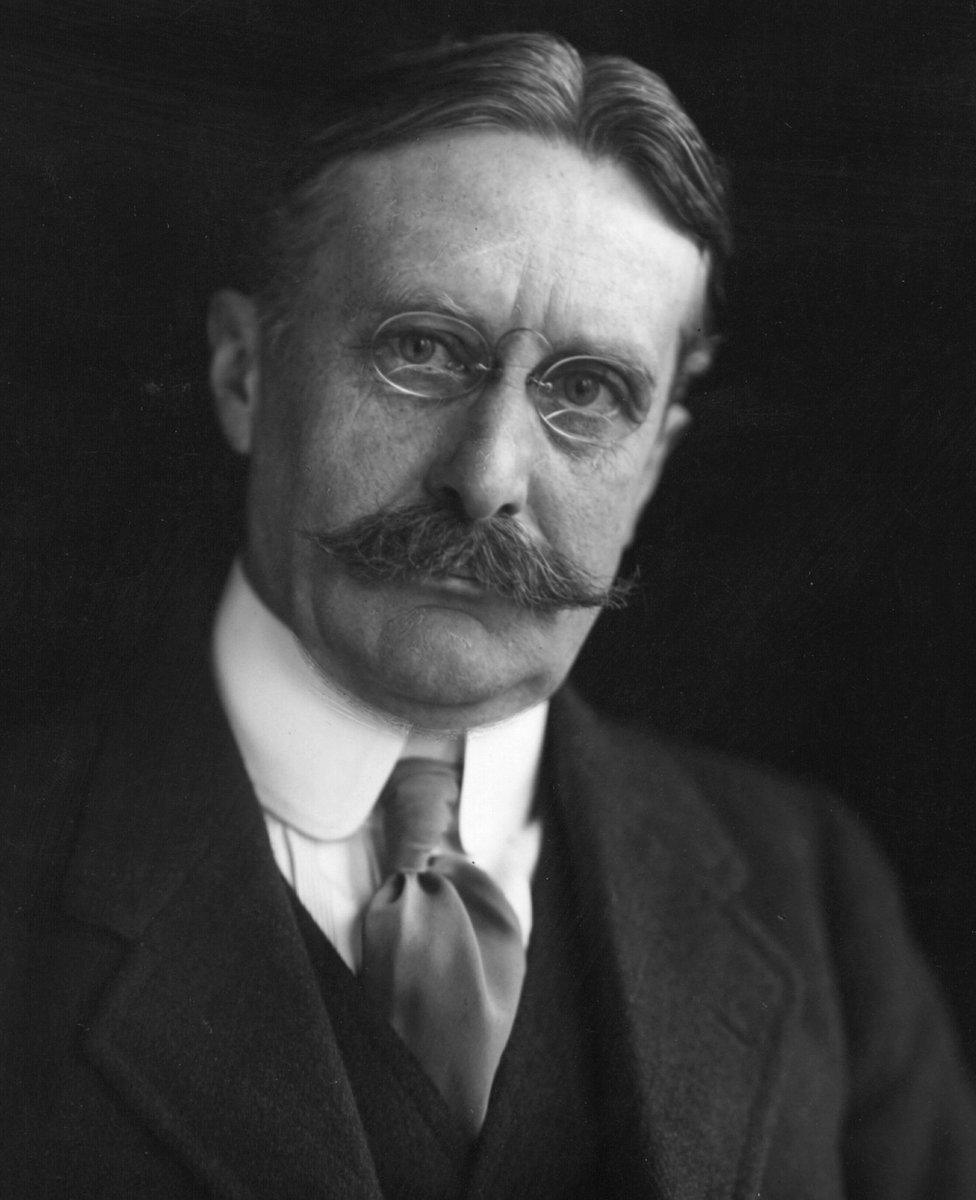

Harry Gordon Selfridge introduced a whole new shopping experience, one honed in the department stores of late-19th Century America.

"Just looking" was positively encouraged.

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that helped create the economic world.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

As he had in Chicago, Selfridge swept away the previous custom of stashing merchandise behind locked glass doors in cabinets, or high up on unreachable shelves.

Instead, he laid out the open aisle displays we now take for granted, where you can touch a product, pick it up, and inspect it from all angles, without a salesperson hovering by your side.

In the full-page newspaper adverts he took out when his store opened, Selfridge compared the "pleasures of shopping" to those of "sightseeing".

Harry Gordon Selfridge revolutionised the shopping experience

Shopping had long been bound up with social display.

The old arcades of the great European cities, displaying their fine cotton fashions - gorgeously lit with candles and mirrors - were places for the upper classes not only to see, but to be seen.

Selfridge had no truck with snobbery or exclusivity. His adverts pointedly welcomed the "whole British public": "No cards of admission are required."

'The bottom of the pyramid'

Management consultants nowadays talk about the fortune to be found at the "bottom of the pyramid" - Selfridge was way ahead of them. In his Chicago store, he appealed to the working classes by dreaming up the concept of the "bargain basement".

Selfridge did perhaps more than anyone to invent shopping as we know it. But the ideas were in the air.

Another trailblazer was an Irish immigrant named Alexander Turney Stewart. Stewart introduced New Yorkers to the shocking concept of not hassling customers the moment they walked through the door, a novel policy he called "free entrance".

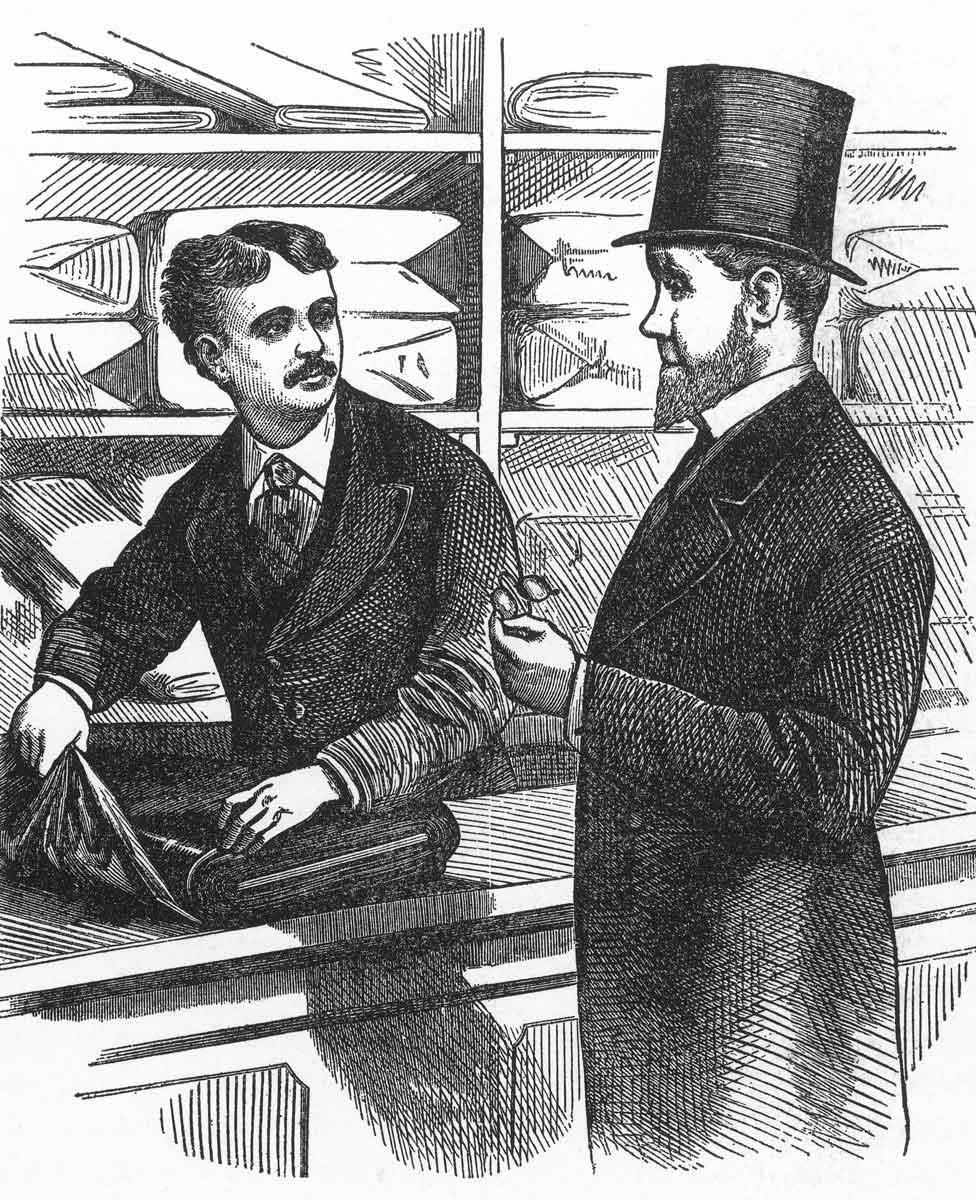

Alexander T Stewart set his prices low, hoping to make profits from high volumes of sales

AT Stewart and Co was among the first stores to practise the now-ubiquitous "clearance sale", periodically moving on old stock at knockdown prices to make room for new.

Stewart also offered no-quibble refunds. He made customers pay in cash, or settle their bills quickly. Traditionally, shoppers had strung out their lines of credit for up to a year.

He also recognised that not everybody liked to haggle, with many welcoming the simplicity of being quoted a fair price, and being told to take it or leave it.

Stewart made this "one-price" approach work by accepting unusually low mark-ups. "[I] put my goods on the market at the lowest price I can afford," he said, "although I realise only a small profit on each sale, the enlarged area of business makes possible a large accumulation of capital".

This idea wasn't totally unprecedented, but it was certainly considered radical.

The first salesman Stewart hired was appalled to discover he'd not be allowed to apply his finely tuned skill of sizing up the customer's apparent wealth and extracting as extravagant a price as possible. He resigned on the spot, telling the youthful Irish shopkeeper he'd be bankrupt within a month.

Cathedrals of commerce

By the time Stewart died, over five decades later, he was one of the richest men in New York.

The great department stores became cathedrals of commerce. At Stewart's "Marble Palace", the shopkeeper boasted: "You may gaze upon a million dollars' worth of goods, and no man will interrupt either your meditation or your admiration."

They took shopping to another level, sometimes literally.

Corvin's in Budapest installed a lift that became such an attraction in its own right that they began to charge for using it. In London, Harrods's moving staircase carried 4,000 people an hour.

In such shops, one could buy anything from cradles to gravestones.

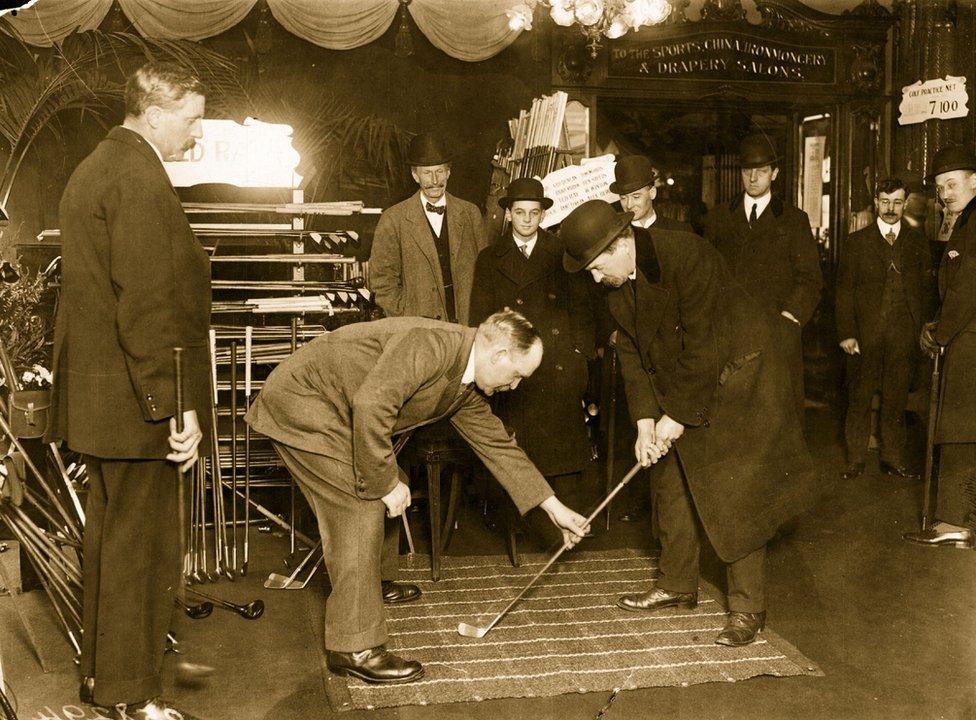

Golf champion John Henry Taylor instructing customers at Harrods in 1914

Harrods offered a full funeral service. There were picture galleries, smoking rooms, tea rooms, concerts. The shop displays bled out into the street, as entrepreneurs built covered galleries around their stores.

It was, says historian Frank Trentmann, the birth of "total shopping".

The glory days of the city centre department store have faded a little. With the rise of cars has come the out-of-town shopping mall, where land is cheaper.

Tourists in England still enjoy Harrods and Selfridges, but many also head to Bicester Village, a few miles north of Oxford, an outlet that specialises in luxury brands at a discount.

But the experience of going to the shops has changed remarkably little since pioneers such as Stewart and Selfridge turned it on its head. And it may be no coincidence that they did it at a time when women were gaining in social and economic power.

There are, of course, some tired stereotypes about women and their supposed love of shopping. But the evidence implies that the stereotypes aren't completely imaginary.

More from Tim:

Time-use studies suggest women spend more time shopping than men.

Other research indicates that this is a matter of preference as well as duty: men tend to say they like shops with easy parking and short checkout queues. Women are more likely to prioritise different aspects of the shopping experience, such as the friendliness of sales assistants.

Social reformer?

This wouldn't have shocked Harry Gordon Selfridge. He saw that female customers offered profitable opportunities that other retailers were bungling.

One quietly revolutionary move was that Selfridges featured a ladies' lavatory, a facility London's shopkeepers had hitherto neglected to provide.

He saw - as other men apparently had not - that women might want to stay in town all day, without having to use an insalubrious public convenience or retreat to a respectable hotel for tea whenever they wanted to relieve themselves.

Selfridges was designed to be as attractive as possible to women

Selfridge's biographer Lindy Woodhead even thinks he "could justifiably claim to have helped emancipate women". That's a big claim for a shopkeeper, but social progress can sometimes come from unexpected directions.

And Harry Gordon Selfridge certainly saw himself as a social reformer.

He once explained why, at his Chicago store, he'd introduced a creche. "I came along just at the time when women wanted to step out on their own," he said.

"They came to the store and realised some of their dreams."

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published27 June 2017

- Published11 May 2017

- Published30 March 2017

- Published24 June 2016