How the barcode changed retailing and manufacturing

- Published

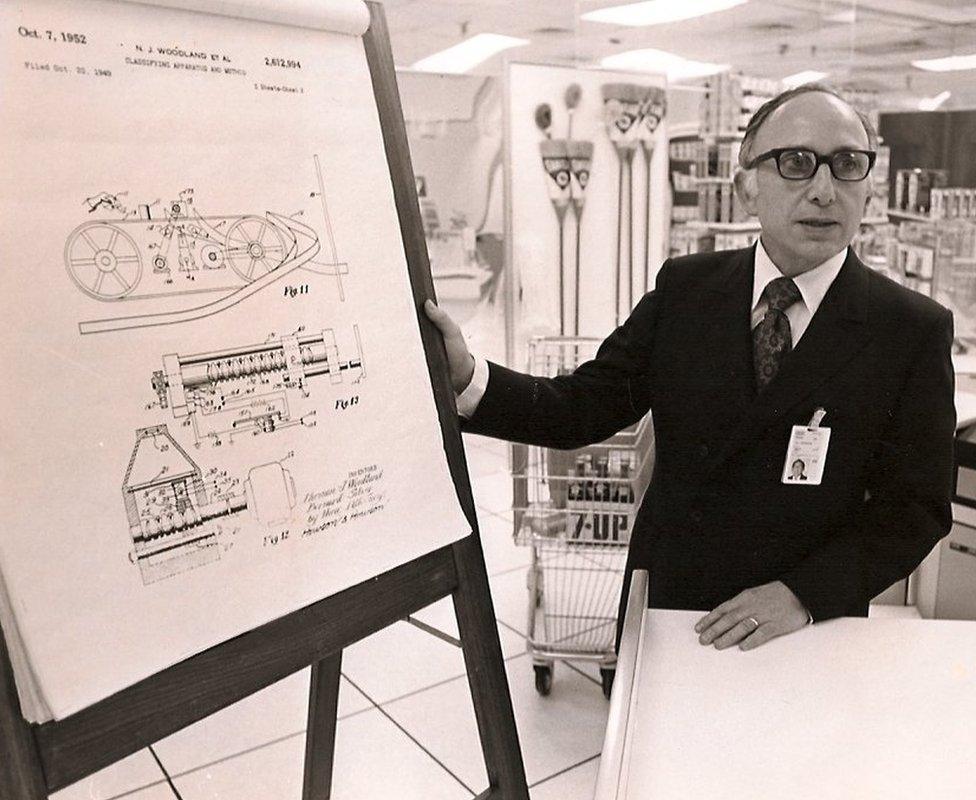

Joseph Woodland explaining his prototype scanner in 1952

In 1948, N Joseph Woodland - a graduate student at the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia - was pondering a challenge from a local retailer: how to speed up the tedious process of checking out in his stores by automating transactions.

A smart young man, Woodland - known as Joseph - had worked on the Manhattan Project during the War, and had designed a better system for playing elevator music. But he was stumped.

Then, sitting on Miami Beach while visiting his grandparents, his fingertips idly combing through the sand, a thought struck him. Just like Morse code used dots and dashes to convey a message, he could use thin lines and thick lines to encode information.

A zebra-striped bull's-eye could describe a product and its price in a code that a machine could read.

The idea was workable, but with the technology of the time it was costly. But as computers advanced and lasers were invented, it became more realistic.

Find out more

50 Things That Made the Modern Economy highlights the inventions, ideas and innovations that have helped create the economic world we live in.

It is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

The striped-scan system was independently rediscovered and refined several times over the years. In the 1950s, an engineer, David Collins, put thin and thick lines on railway cars so they could be read automatically by a trackside scanner.

In the early 1970s, IBM engineer George Laurer figured out that a rectangle would be more compact than Woodland's bull's-eye.

He developed a system that used lasers and computers that were so quick they could process labelled beanbags hurled over the scanner.

Retailers v producers

Joseph Woodland's seaside doodles had become a technological reality.

Meanwhile American's grocers were also pondering the benefits of a pan-industry product code.

In September 1969, members of the administrative systems committee of the Grocery Manufacturers of America met their opposite numbers from the National Association of Food Chains. Could the retailers and the producers agree?

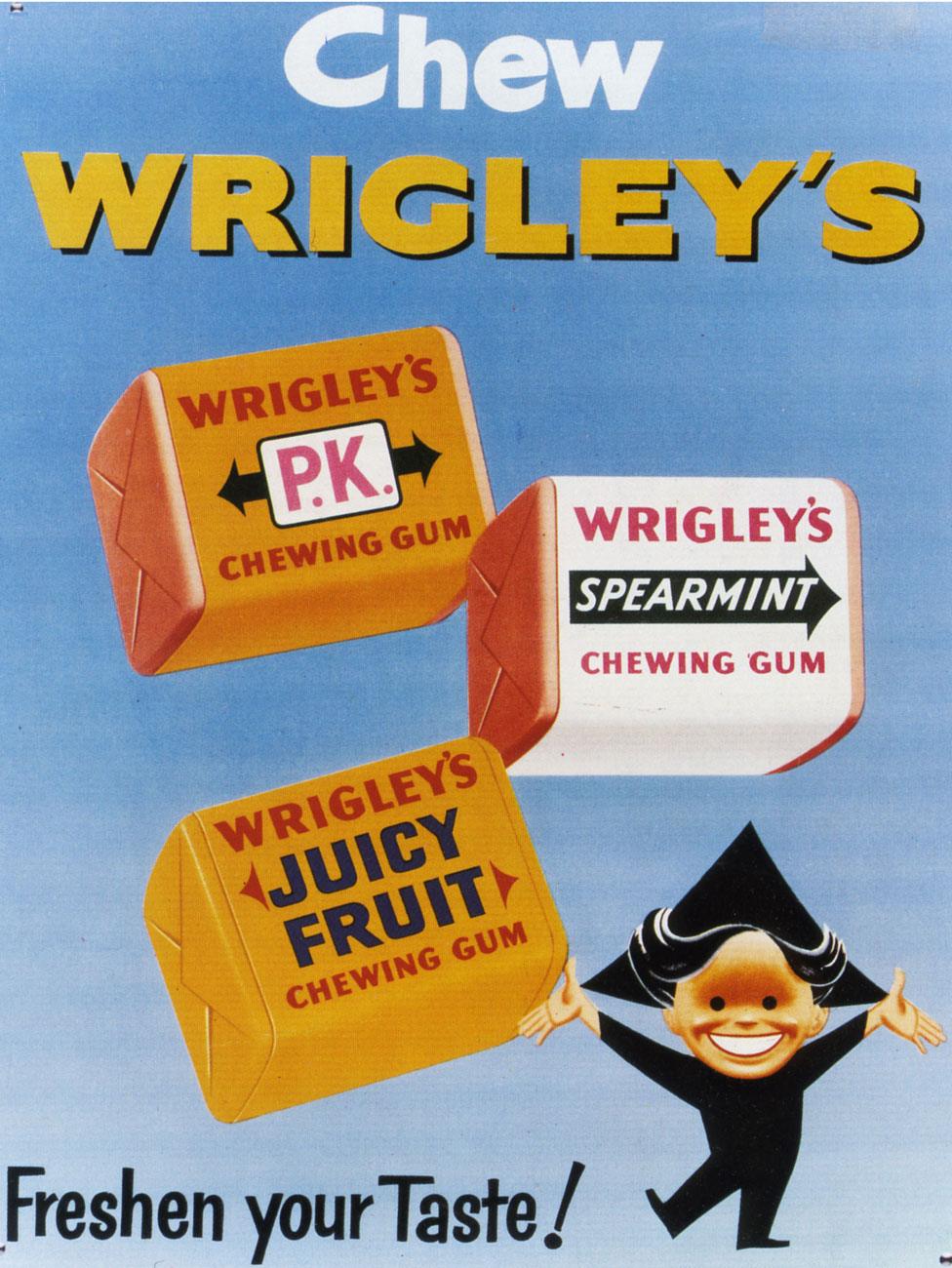

Wrigley's chewing gum would be the first product sold via a barcode in 1974

The GMA wanted an 11-digit code, which would encompass various labelling schemes they were already using. The NAFC wanted a shorter, seven-digit code, which could be read by simpler and cheaper checkout systems.

The meeting broke up in frustration. Years of careful diplomacy - and innumerable committees, subcommittees and ad hoc committees were required before, finally, the US grocery industry agreed upon a standard for the universal product code, or UPC.

It all came to fruition in June 1974 at the checkout counter of Marsh's Supermarket in the town of Troy, Ohio, when a 31-year-old checkout assistant named Sharon Buchanan scanned a 10-pack of 50 sticks of Wrigley's juicy fruit chewing gum across a laser scanner, automatically registering the price of $0.67 (£0.55).

Shifting power

The gum was sold. The barcode had been born.

We tend to think of the barcode as a simple piece of cost-cutting technology: it helps supermarkets do their business more efficiently, and so it helps us to enjoy lower prices.

But the barcode does more than that. It changes the balance of power in the grocery industry.

That is why all those committee meetings were necessary, and it is why the food retailing industry was able to reach agreement only when the technical geeks on the committees were replaced by their bosses' bosses, the chief executives.

Barcode technology required a significant investment for smaller retailers

Part of the difficulty was getting everyone to move forward on a system that did not really work without a critical mass of adopters.

It was expensive to install scanners. It was expensive to redesign packaging with barcodes - bear in mind the Miller Brewing Company was still printing labels for its bottles on a 1908 printing press.

The retailers did not want to install scanners until the manufacturers had put barcodes on their products. The manufacturers did not want to put barcodes on their products until the retailers had installed enough scanners.

But it also became apparent over time that the barcode was changing the tilt of the playing field in favour of a certain kind of retailer. For a small, family-run convenience store, the barcode scanner was an expensive solution to problems they did not really have.

But big supermarkets could spread the cost of the scanners across many more sales. They valued shorter lines at the checkout. They needed to keep track of inventory.

More from Tim Harford

With a manual checkout, a shop assistant might charge a customer for a product, then slip the cash into a pocket without registering the sale. With a barcode and scanner system, such behaviour would become conspicuous.

And in the 1970s, a time of high inflation in America, barcodes let supermarkets change the price of products by sticking a new price tag on the shelf rather than on each item.

The benefits of scale

It is hardly surprising that as the barcode spread in the 1970s and 1980s, large retailers also expanded. The scanner data underpinned customer databases and loyalty cards.

By tracking and automating inventory, it made just-in-time deliveries more attractive, and lowered the cost of having a wide variety of products. Shops in general - and supermarkets in particular - started to generalise, selling flowers, clothes, and electronic products.

Wal-Mart founder Sam Walton was able to exploit the possibilities barcodes offered

Running a huge, diversified, logistically complex operation was all so much easier in the world of the barcode.

Perhaps the ultimate expression of that fact came in 1988 when the discount department store Wal-Mart decided to start selling food.

It is now the largest grocery chain in America - and by far the largest general retailer on the planet, about as large as its five closest rivals combined. Wal-Mart was an early adopter of the barcode and has continued to invest in cutting-edge computer-driven logistics and inventory management.

The company is now a major gateway between Chinese manufacturers and American consumers. Its embrace of technology helped it grow to a vast scale, meaning it can send buyers to China and commission cheap products in bulk.

From a Chinese manufacturer's perspective, you can justify setting up an entire production line for just one customer - as long as that customer is Wal-Mart.

The cost of adopting barcodes initially put off some manufacturers such as Miller

Geeks rightly celebrate the moment of inspiration as Joseph Woodland languidly pulled his fingers through the sands of Miami Beach - or the perspiration of George Laurer as he perfected the barcode as we know it.

But it is not just a way to do business more efficiently. It also changes what kind of business can be efficient.

The barcode is now such a symbol of the forces of impersonal global capitalism that it has spawned its own ironic protest. Since the 1980s, people have been registering their opposition to "The Man" by getting themselves tattooed with a barcode.

That countercultural fashion statement recognises something important.

Yes, those distinctive black and white stripes are a neat little piece of engineering. But that neat little piece of engineering has changed how the world economy fits together.

Tim Harford writes the Financial Times's Undercover Economist column. 50 Things That Made the Modern Economy is broadcast on the BBC World Service. You can find more information about the programme's sources and listen online or subscribe to the programme podcast.

- Published29 December 2016

- Published20 December 2016

- Published13 December 2012

- Published7 October 2012