Ben Broadbent: Rate rise may be higher than market expects

- Published

- comments

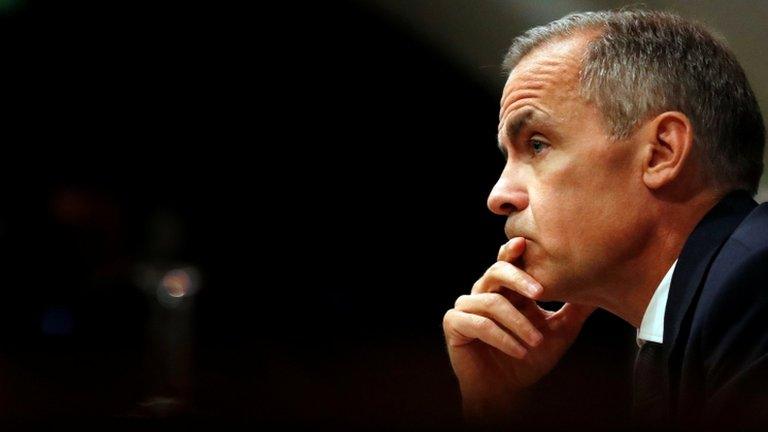

UK interest rates may have to go up by more than the market expects in the future, Bank of England deputy governor Ben Broadbent has told the BBC.

He said the drop in sterling following the Brexit vote had fuelled inflation.

Mr Broadbent said there was a "trade off between stabilising inflation and keeping the economy going".

But he said the UK was "a little bit" better placed to cope with an interest rate rise.

Mr Broadbent said the Bank's Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) believed there would need to be more rate rises than those expected by the financial markets.

"The MPC said given the other assumptions in its forecast it thought probably there would need to be rate rises, and indeed more rate rises than those priced into the interest rate curve in future than the financial markets expect.

"I do think the time is likely to come when rates will go up generally."

On Thursday, the Bank kept interest rates unchanged and cut its economic growth forecasts.

The Bank voted 6-2 to keep interest rates on hold at 0.25%, a level they have been at since August last year.

Pockets of debt

Mr Broadbent said there should not be undue concern following a rate raise.

"One shouldn't overdo this. If and when it happens there will be a lot of talk about the first rate rise since 'x'. But it's just a rate rise and we got perfectly used to rate rises of this size in the past."

He said the objective of the MPC was not "the path of interest rates but the stability of inflation in the medium term and subject to that the stability of the economy".

The Bank is concerned that uncertainties about Brexit appear to be putting companies off new investment, despite an increase in profits for exporters following the fall in the value of the pound since last year's referendum.

Mr Broadbent said he understood the difficulties of ordinary consumers, who are being squeezed by a combination of rising inflation and wages that are failing to keep pace with price increases.

The deputy governor said there were some areas of household debt that had been growing quite a lot, namely borrowing on credit cards and the buying of cars through Personal Contract Purchases.

But he said the Bank's monetary policy makers were not too worried about the debts of British households because consumer credit, relative to incomes, remained much lower than its level before the financial crisis.

He said: "The level of consumer credit is less compared to incomes than it was during the (financial) crisis". He also pointed out that interest rates were lower now than they were then.

"It is absolutely right that the prudential side of the Bank ... should be concerned about pockets of debt that are growing very, very quickly.

"The MPC does not think this is a first-order macro issue for the economy."

- Published3 August 2017