Has eurozone stimulus done its job?

- Published

The European Central Bank (ECB) is under mounting pressure to decide how much longer its enormous stimulus package will continue.

The bank's president, Mario Draghi, says it will make a decision in the autumn about the stimulus measures.

More than 2.3 trillion euros (£2.1tn) will have been pumped into the eurozone economy by the end of the year in a process known as quantiative easing (QE).

But the bank needs to decide if the 19-country bloc is ready to come off the emergency measures introduced in response to the financial crisis.

And if so, how best to do it without threatening the eurozone's recovery.

What is the eurozone stimulus?

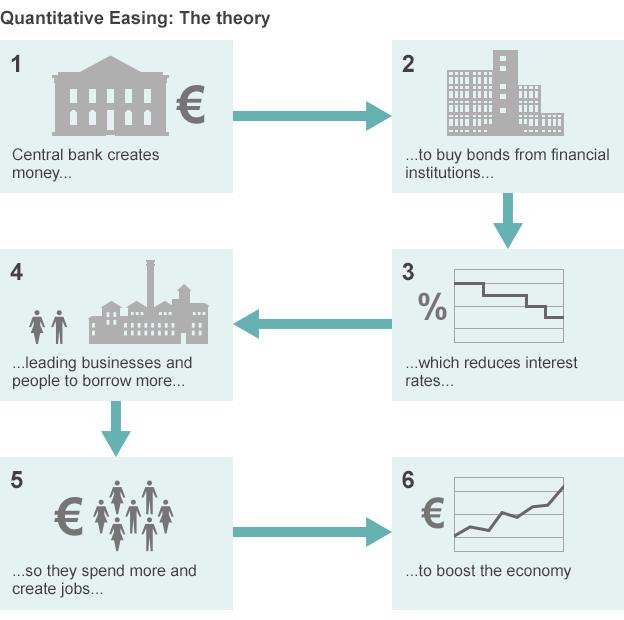

The ECB introduced the huge bond-buying programme in 2015 as it looked to kick-start the bloc's ailing economy.

The bank, which had already slashed interest rates to cope with the eurozone debt crisis, followed the US Federal Reserve and Bank of England by introducing QE.

Analysts say Mr Draghi faces a difficult balancing act on QE

"QE is what central banks do when everything else has failed," Gilles Moec, chief European economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch, told the BBC.

More than two years later, the ECB is still buying 60bn euros of government and corporate bonds a month.

How to wean the eurozone off that artificial support - due to expire at the end of December "or beyond if necessary" - is the big question facing Mr Draghi.

Has it worked?

The eurozone economy is growing at a much healthier pace than it was in 2015 - but it is hard to prove how much this is down to QE.

Figures released on Thursday confirmed the bloc's economy grew by 0.6% in the three months to June, a faster pace than the UK.

That leaves it on track to grow by 2.1% this year, which would be the fastest rate in a decade, according to analysts at IHS Markit, external.

Mr Moec says QE frees up banks to lend to more people and lowers the cost of borrowing for companies.

It also increases the price of financial assets, which should feed through to more consumer spending, he says.

"In Europe what you do by doing this is that you trigger what is called a 'wealth effect'. People feel richer, and as they feel richer they spend more," Mr Moec says.

Mr Draghi said in a speech last month that policies like QE had been a success both sides of the Atlantic.

They have "made the world more resilient", he said, but he also recognised that gaps remain in understanding these relatively new tools.

However, critics say the economic stimulus has not dealt with the underlying weaknesses in the eurozone.

Not all parts of the bloc are growing so strongly, and while unemployment is coming down, it is still above 17% in Spain and 11% in Italy.

Should the ECB start winding it down?

Others argue that the bond-buying programme promotes inequality, because it favours those with assets and, combined with record low interest rates, harms savers.

Last month, Lord Macpherson, who was permanent secretary to the Treasury when the Bank of England started QE in 2009, likened it to "heroin".

Economies "need ever increasing fixes to create a high", but the negative side effects are increasing, he said.

The ECB in Frankfurt has a balance sheet of 4.5tn euros following QE

Eurozone inflation is also still stubbornly below the ECB's 2% target, which is giving the bank's policymakers pause for thought.

By taking away the stimulus, will the economy and inflation also slow down?

The cost of living rose by 1.5% in the year to August, and some analysts predict the euro's recent gains against the dollar - rising 13% this year - will further depress inflation by making imports cheaper.

But there are members of the ECB - known as "hawks" - who think the time has come to drop the emergency measures and get the bank back to normal.

What are the risks?

QE has swelled the ECB's balance sheet to about 4.5 trillion euros, which is close to half the eurozone's GDP, according to Mr Moec.

Central banks have never tried anything of this magnitude, he says. "The ECB is going to tread very, very carefully on the way back."

Mr Draghi has a difficult balancing act, says Michael Hewson, an analyst at CMC Markets.

Against the hawks, there are those who worry that cutting QE prematurely could prompt a slowdown in some of the weaker countries of the euro area, he says.

"It is this more than anything that highlights the dilemma for policymakers in trying to set a monetary policy for an economy that has full employment in Germany, with Italy and Spain who remain a long way short of it," he adds.

- Published1 November 2022

- Published23 August 2017