The collapse of Northern Rock: Ten years on

- Published

Northern Rock was a key sponsor for Newcastle United

In the summer of 2007, Newcastle had much to look forward to. The Toon - Newcastle United - had a new owner, the billionaire retail tycoon Mike Ashley, and much was expected under the management of Sam Allardyce.

The performance of the team's shirt sponsor, Northern Rock, was a source of pride; after decades of hard times following the end of shipbuilding and mining, the North East had a new economic champion, one that was giving the financial services giants of the South a real run for their money.

The former building society had demutualised and scaled the heights of the FTSE 100, the elite club of Britain's biggest quoted companies, and in the process had become the fourth biggest bank in the UK by share of lending.

The chairman, Matt Ridley, summed it up in the annual report, lauding "another excellent year" and said "our strategy of using growth, cost efficiency and credit quality to reward both shareholders and customers continues to run well."

Toxic fuel

A few months later, Northern Rock's empire was in ruins. The fuel it had used to grow so quickly turned out to be toxic.

Northern Rock had borrowed heavily on the international money markets

Rather than using customer deposits as the source of funds to lend out to homeowners, it borrowed in the international money markets.

When the sub-prime crisis hit America, those markets took fright, and stopped lending to anything that looked like it might be over-exposed to the housing market. Northern Rock was an obvious first casualty.

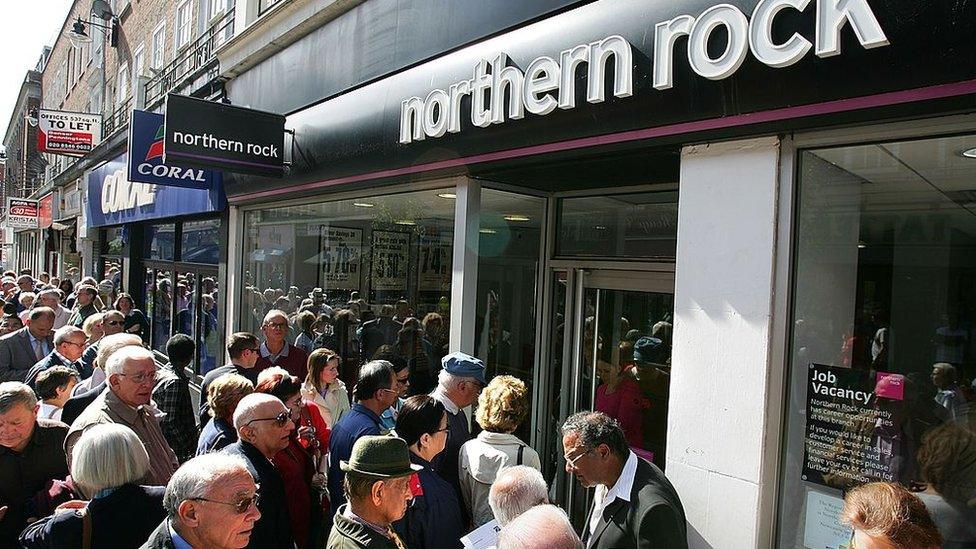

The BBC broke the news that it needed Bank of England support 10 years ago tomorrow, and the day after there were queues outside branches, the first run on a British bank in 150 years. After limping on for a few more months, Northern Rock was nationalised in February 2008.

Regional shock

Councillor Nick Forbes, leader of Newcastle City Council, remembers walking out of the civic offices to nearby Northumberland Street where Northern Rock had its main city centre branch. "There was a queue outside going right down the street. That really was the first sign that something was wrong. No-one really saw it coming."

Customers queued for hours to take out their savings

Northern Rock's demise - it was split into "bad" and "good" sets of assets and operations, with Virgin Money buying the latter - was a shock to the region's economy, as was the banking crisis that followed.

"We were early into recession and late out," said Mr Forbes. "It's only now really that we have recaptured that lost ground."

About 2,500 jobs were lost. There was another heavy blow, little understood outside the North East - the loss of the Northern Rock Foundation, a charitable trust which received 5% of the bank's profits each year.

Many who lost their savings want the government to change its mind on compensation

It had given £235m to good causes before the bank was nationalised and broken up. Mr Forbes is now pressing the Treasury to give back some of the profits it expects to make from its intervention on Northern Rock to make up for the loss of the foundation.

Northern Rock shareholders are also making a claim on the potential profits, which independent experts think could eventually reach about £8bn.

An association of small shareholders, many of whom lost their life savings when the bank was nationalised, has asked the chancellor to think again on compensation, which has been denied before.

Any surplus from Northern Rock's privatisation should go to taxpayers, says the Treasury

Jon Wood, a fund manager who was a big Northern Rock shareholder and has been severely critical of the Bank of England's action, is also thought be to considering fresh legal action. The Treasury has said that any surplus from the Northern Rock nationalisation should compensate taxpayers for the amounts risked in the rescue.

Lessons learned

A decade on, important strands of "the run on the Rock" story are only now being uncovered. In an interview with the BBC Gary Hoffman, who was parachuted in as chief executive after privatisation, said he found an organisation with an unquestioning - and unhappy - culture.

"The management had completely lost touch with the coal face, and did not know what was happening. There was an attitude that you did not question what was going on, which was a tragedy because there were extremely good people at the bank."

Hoffman reveals that the Treasury had considered all options for the future of the bank when he was in charge - not just a sale to a banking rival, but also a refloating of the bank as an independent business, and its complete run-down and closure.

The collapse was the first sign in Britain of the coming global financial crisis

Other senior banking sources have told the BBC that the last option - closure - was the favourite right up until Christmas Eve 2008, when the bank's leadership was able to convince the Treasury it could be sold as a going concern.

Mr Hoffman says that the UK's banking sector is now safer than in the run-up to the crisis, with greater capital reserves at the big institutions. Others disagree, however, saying the increases have been largely illusory.

Kevin Dowd, professor of finance and economics at the University of Durham, says changes in bank regulations have not greatly improved banks' resilience.

"The Bank of England looks at the book value of bank assets - the value that they themselves put on their assets. But if you look at the stock market, investors don't believe it because most of our big banks have stock market values less than their book values."

- Published11 September 2017

- Published11 September 2017

- Published9 August 2017