How do you like your wine – with a cork or screw-cap?

- Published

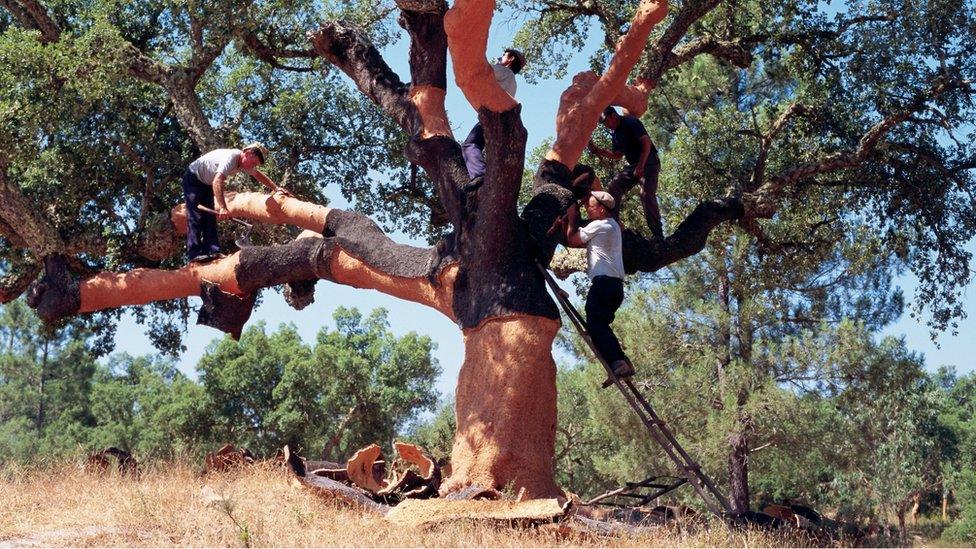

Cork is harvested from a type of oak tree, with Portugal the world's largest producer

If you are a regular wine drinker it is almost certain that you have opened a corked bottle or two in your time.

As a result of a tainted cork, the wine smells and tastes unpleasant - all musky and mouldy.

After the initial disappointment, you then have the worry of trying to get your money back from the wine shop or supermarket.

Or you may face an awkward conversation with a supercilious wine waiter, whose boss might not take kindly to reimbursing you, especially if it was an expensive bottle and the taint isn't too prominent.

Figures for how many cork-sealed wine bottles are affected by cork taint are hotly disputed, but a 2007 study, external put it as high as one in 10.

With reputations on the line, and money lost on wine tipped down sinks, it is not surprising that winemakers around the world are continuing to ditch corks for metal screw-cap openings on their bottles. So much so that cork went from sealing 95% of wine bottles globally in the 1990s, to just 62% in 2009.

This is bad news for Portugal's cork producers, who supply more than half the world market from forests of cork oak trees in the south of the country. However, the industry is fighting back.

Natural corks are "punched" out of strips of cork

But first, what exactly is cork taint? It is caused by a chemical compound known as TCA.

In very simple terms, TCA is created by tiny airborne fungi that have attached themselves to the cork. It isn't harmful, but it can make your wine taste bad, or alternatively strip it of flavour.

Carlos de Jesus, director of marketing at Portugal's largest cork producer, Amorim, admits that about 13 years ago things looked bleak for the future of natural corks in some countries.

"Of course everything has its upsides and downsides, but there was a moment there around 2003-04 where the image of cork not having a future was taking place in some markets, mainly in Australia and New Zealand," he says.

The trees grow the cork back over a nine-year period

Fast-forward to today, and Mr de Jesus says that Amorim is leading efforts to prevent any TCA infected corks getting into the system.

It does this using a process it calls "NDTech", whereby it uses hi-tech sensor machines to weed out any bad corks.

Mr de Jesus adds: "We can do that analysis not in minutes... but in seconds. We can now give an individual guarantee, cork by cork."

And despite the big move to screw-caps, particularly still in Australia and New Zealand, Amorim now produces 4.4 billion corks per year, out of a total 12 billion industry-wide.

This compares with 4.7 billion screw-caps per annum, and 1.8 billion bottles with plastic stoppers.

Despite the hard work of Amorim and other members of the Portuguese cork industry to tackle TCA, Australian wine boss Mitchell Taylor says he doesn't expect he will ever go back to corks.

A total 12 billion natural corks are made each year

Mr Taylor is managing director of Taylors Wines (known as Wakefield Wines in the UK), based in South Australia's Clare Valley. In 2004 it was the first major Australian winery to decide to seal all its wines under screw-cap.

"We were finding we had TCA and random oxidation problems with up to 10-15% of our wines, and we were able to eliminate that overnight," he says.

"The world has moved forward, I compare going back to cork as the horse and cart, it's a great form of transport, but really we've moved on in modern technology."

Yet while Mr Taylor is adamantly against natural corks, it remains the case that the vast majority of top European and American wines are still sealed with them.

In addition to being a case of tradition, and a continuing perception that the wine will be of better quality, natural corks have a proven record over the centuries of helping fine wines to mature by letting in tiny amounts of oxygen, something screw-caps cannot properly replicate.

Grgich Hills Estate in California's Napa Valley is one winemaker that is mainly sticking with natural corks, which it uses on 70% of its wines.

It typically pays about 70-93 cents (52-69p) per high-quality Portuguese cork.

Australian wine firm Taylors was the first in that country to switch completely to using screw-caps

Ivo Jeramaz, Grgich's vice president of grape growing and production, says: "These days our research points to three to five corks per 1,000 being affected by TCA, not three to five per 100, so it's far less than it used to be."

He adds that "top notch expensive wines" need natural corks, "just as you wouldn't drink it from a paper cup".

More stories from the BBC's Business Brain series looking at interesting business topics from around the world:

Are changeable heels the end to women's sore feet?

Do the colours you wear at work matter?

Grgich doesn't use any screw-caps at all, and instead for the other 30% of its bottles it is experimenting with a new cork called "Diam".

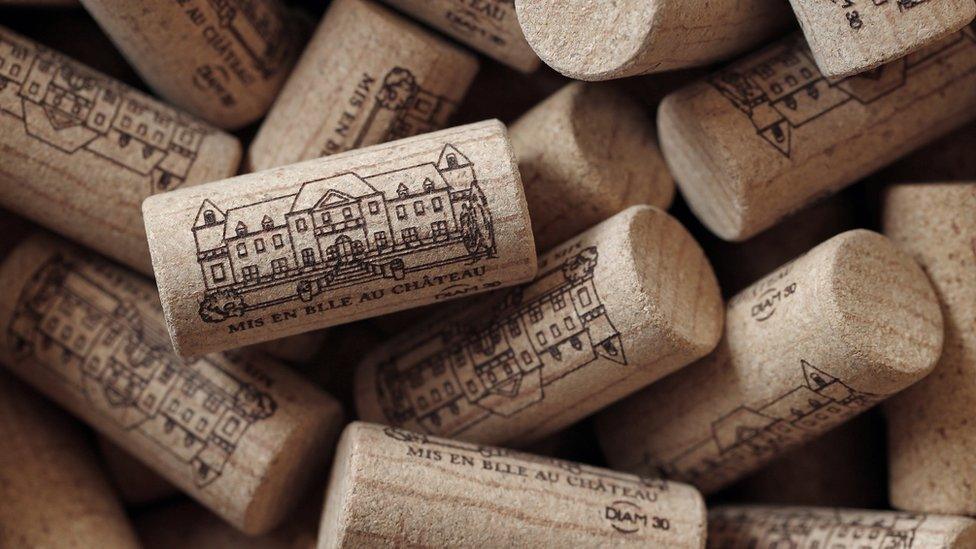

Developed by a French firm of the same name, Diam corks are made by milling cork into granules which are treated with carbon dioxide to remove any TCA, before being pressed and glued into a cork shape.

Diam corks are now growing quickly in popularity, particularly among French winemakers aiming at the middle market.

Diam corks are made from treated cork granules, which are then pressed into shape

Mark Pardoe, a master of wine at UK merchant Berry Bros & Rudd, says that natural cork is still the "preferred closure for wines that require cellarage".

He adds: "Its elasticity and ability to allow a very gentle oxidation when a wine is correctly stored makes it a still-unsurpassed closure for long-term wines.

"Progress in cork processing methods mean that some cork producers are now able to give guarantees, and traceability, to insure the drinker against increasingly infrequent "corked" bottles.

"And, as such, cork is still the premium wine closure, although every premium winery experiments with other closures."

The Portuguese cork industry is also keen to stress its environmental credentials, particularly the fact that trees are not cut down to harvest the cork. Instead the cork is stripped from beneath the bark, and then grows back over a nine-year period.

Screw-caps can remove the threat of TCA, but some question whether they work for wines that need to be cellared for many years

Michael Colangelo, vice president of New York-based PR firm Colangelo & Partners, which is promoting Portuguese cork in the US, says: "Many people still don't understand the sustainability of cork, in that it's like shearing a sheep - you don't kill the sheep to get the wool."

Ramiro Baptista, manager of cork firm Portugalia, adds that the global wine industry is large enough for all forms of closure to have a bright future.