Is now the time to raise interest rates?

- Published

Is the economy moving fast enough to bear a rate rise?

It's been 10 years since the UK last saw interest rates rise.

Back then, the iPhone had only just been unveiled, Twitter was a one-year old mystery and Instagram didn't even exist.

Hard to imagine life without these things now, but interest rates of 5.75% and Gordon Brown as prime minister seem strangely alien.

After that 0.25% rise, the world of monetary policy went into a tailspin, with central banks imposing a rapid series of interest rate cuts as it attempted to outrun the credit crunch.

Finally, in March 2009 they hit a record low of 0.5% until being cut again to 0.25% in August 2016 in the aftermath of the shock Brexit vote.

It will certainly be an unfamiliar feeling to see rates rise, although discussions about lifting them have rumbled during much of that almost nine-year period of record lows.

Hold the phone: The last time rates went up the iPhone had just come out in the US

Next month is hotly tipped to be the one that changes the direction of interest rates. Last month, Mark Carney dropped what was seen as his biggest hint yet that rates would be increased soon, possibly in November.

Granted, the economic backdrop is difficult to decipher.

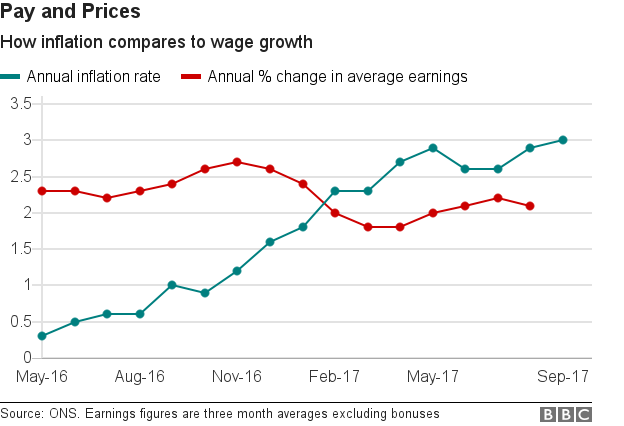

This week saw inflation at a five-year high, weak retail sales figures on Thursday - but government borrowing figures on Friday way better than expected.

And the underlying picture is of sluggish economic growth, persistently weak productivity, and wage rises that lag inflation and eat into earning power.

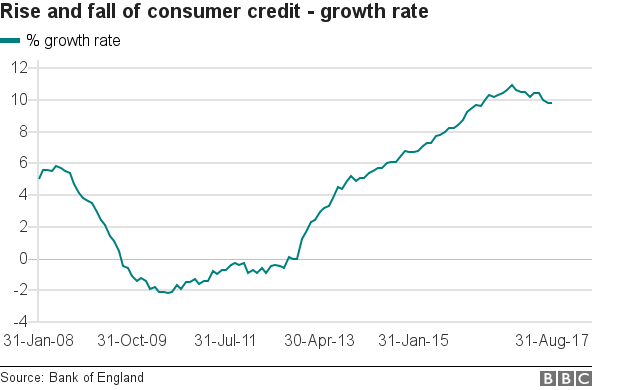

On top of that, household debt is rising five times faster than earnings and is more than £200bn - a state of affairs that Bank of England governor Mark Carney has remarked on often.

We ask two former rate-setters from the Bank of England's Monetary Policy Committee whether now is the time to bite the bullet.

The case for: Dame Kate Barker, non-executive director at Taylor Wimpey and Man Group, MPC member 2001-2010

"First of all, I would try very hard not to give advice to the Monetary Policy Committee. When you're on it, you have so much more information to go on. But I might be tempted to join the 'Raise' group.

"I am concerned about the level of credit."

She believes the Brexit effect is one that is out of the Bank's control: "You can cut the level of credit, you can't really do anything with monetary policy to offset the difficulties that are inevitable because of Brexit.

"We are going to go into a period of economic difficulty that will be worse if we have people with high borrowing."

But won't higher interest rates make life even worse for those with high debts, by simply making them harder to pay off?

"We have to try to keep the economy in reasonable balance. There was a failure to pay enough attention to what was going on with credit in households and small businesses in the run-up to the crisis.

"The debt position is precarious. Sooner or later, we are going to have to move to raise rates. If not, even more people will be taking on credit. We need to encourage savers and discourage borrowers."

She accepts there is a worry about higher inflation, while the tightness of the labour market - which should mean higher wages - getting tighter still if fewer people come to the UK to work from the European Union.

She accepts the retail sales figure for September was weak, but points out that it does not capture the whole of what the consumer is doing, and that the GDP numbers are "fairly feeble".

Her vote is to move rates higher now.

The case against: Dr Sushil Wadhwani, founder of Sushil Wadhwani Asset Management, MPC member 1999-2002

"In essence, in an ideal world, it would have been good if rates had been raised a year, or two, or three ago and were now at a higher level.

"That would have helped to prevent the build-up of consumer debt that Kate and so many of us are concerned about.

"However, at this stage, the horse has bolted. The debt has already built up now and I'm not sure the macro-economic conjuncture justifies a rise at this stage," Dr Wadhwani says.

He accepts higher inflation, which is outstripping wages, is a worry, but says that will work itself out of the system: "We all know that inflation is higher because of temporary factors relating to the pound and Brexit. Wage rises are benign and growth is pretty anaemic - and could get even weaker.

"It seems odd to be raising rates at a time when growth is likely to weaken further. It would be much better to hang on and wait for the uncertainty surrounding Brexit to lift."

He also sees Kate Barker's point on Brexit being none of the Bank of England's doing - and hard for it to counter: "It's true that the bank has no responsibility to deal with Brexit per se - it's a political decision.

"You are, though, dealt a hand and you have to deal with it - Brexit appears to reduce demand more than it reduces supply, so as a bank, you have to keep your foot on the pedal [keep rates low] to stimulate the economy, and that's what it should do.

"No real policy mistake is going to be committed by not raising rates at this stage."