Is the productivity puzzle the chancellor's biggest problem?

- Published

- comments

At this Wednesday's Budget, the man whose pronouncements will be most carefully watched may not, for once, be the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Philip Hammond.

Instead it will be the former journalist, economist and now director of the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR), Robert Chote.

Why? Because it's down to him to arrive at a new, much more realistic view of a long, drawn-out economic calamity whose impact the government is only now accepting in full: a decade of flat productivity.

Until 10 years ago, productivity was the motor that drove economic growth. Its definition is nothing more complicated than the value we produce per worker (or per hour).

If you're a coffee shop worker, it's the value added in the sales of coffees, tea and food. On a pie-making production line, it's the pies you turn out. If you're a lorry driver, it's how much you deliver.

Now think of that lorry driver stuck in a traffic jam. With too little investment in new roads and too many cars and lorries using them, his trips are slower. However hard he works, he can't keep delivering more than before. His productivity stalls.

That flat productivity has knock-on effects. The driver's employer used to get a little more output from each worker each year - so they each made the company a bit more revenue. That made it possible to afford pay rises above inflation each year.

In turn that meant the driver could afford to buy more, boosting spending, and therefore growth, in the rest of the economy. And the chancellor of exchequer also benefited when the driver was paid, collecting higher income tax and national insurance, and when the driver spent money, because more VAT came in.

Until very recently the OBR was assuming that happy state of affairs would return. The 2008 crash had done its damage. But all being well the economy would recover - and with it the tax revenues that would enable the chancellor to close the gap between his income and his spending (also known as the Budget deficit).

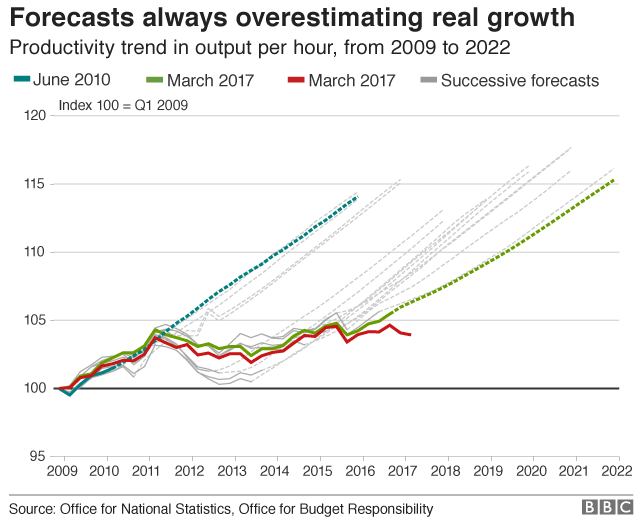

Now have a look at the chart. The OBR's been assuming at each Budget for years that output per worker would get back to its pre-crisis rate of growth - where we each produce about 2.1% more each year.

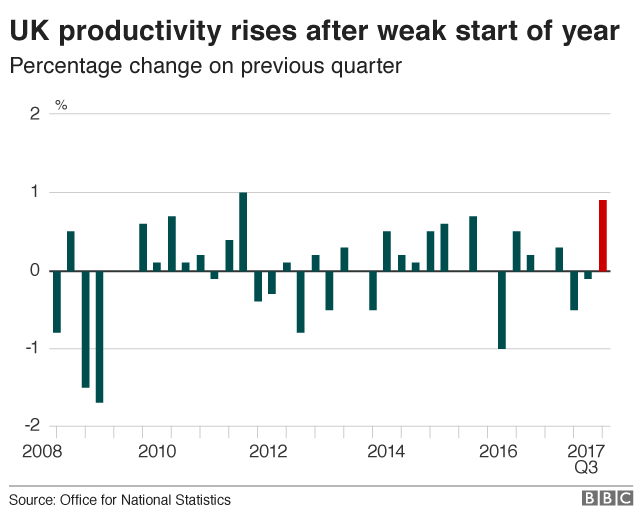

Instead, the typical rate of growth in the past five years has been 0.2%. As Robert Chote said last month: "Our assumption that productivity growth would return to a more normal rate within a few years reflected a judgement that whatever factors were depressing it in the wake of the financial crisis would fade as it receded further into the past.

"But as the period of weak performance gets longer, the explanations that people pointed to immediately after the crisis look less convincing and others seem more plausible."

Hope of a recovery has been replaced by acceptance of weaker productivity growth - itself a large part of the reason why wages too are no higher in real terms than they were 11 years ago.

On Wednesday Mr Chote will publish his revised, more realistic assumption, accepting that something profound has changed. Accepting weaker productivity growth in the years to come means accepting lower tax revenue for the chancellor, which in turn means less scope for spending more, cutting taxes or reducing the deficit.

But hold on: it's not as if we've been in recession all that time. Haven't we had economic growth?

The answer is - yes. But not the sort we used to have. From one angle, an economy is simply people and their economic activity. If you add hundreds of thousands of people to the workforce each year, through people working into retirement and through immigration, then the economy will grow larger.

But GDP per capita - the amount we produce per person - has grown far more slowly.

It's not just the UK that has suffered from weak productivity growth, it's across all advanced countries. But in the UK, the weakness is worse. A period of weak productivity and weak wages this long hasn't happened since the 1860s.

The words of the OBR's Robert Chote may be significant on Budget day

One reason is weak business investment. A company trying to meet an expanding order book can try one of two methods: hire a few more people, or make its existing workforce more productive by investing in new, more efficient technology. As long as its cheaper and less risky to hire cheap labour, the business may hold off investment.

But weaker private investment - and private investment has in any case been growing recently - can't account for the whole effect.

Another attempted explanation is weak training and poor infrastructure, another is weak spending on research and development - all of which play a role but none of which can explain in full the breakdown of what is normally the engine of economic growth.

The government hopes to address some of those weaknesses in a new industrial strategy, originally due to be published before the Budget but now postponed until next week.

Michael Jacobs, former Downing Street economic adviser and now director of the Institute for Public Policy Research, says the real problem isn't the obvious industries, such as engineering or pharmaceuticals, where growth relies on big investment and high skills.

"The UK's productivity problem lies in the vast majority of ordinary firms, in sectors such as retail, light manufacturing, tourism, hospitality and social care," he says.

"Unless the White Paper includes a plan to raise productivity in these sectors, it will still not be addressing the real issue."