Why banks will share your financial secrets

- Published

Your financial information, such as what you spend and where, and how often you go into debt is private. It is information only available to you and your bank.

It has been like that for years, but all that is to change.

Customers of nine of the biggest UK banks have received letters and emails in recent weeks informing them that their information can be shared, securely, with other firms. All they need to do is give their permission.

The UK's competition watchdog says this so-called Open Banking regime will revolutionise many people's financial lives, helping them get better deals.

Others are far more sceptical. So how does all this work and what does it mean for you?

What is it?

Your financial data is valuable. For example, a loan provider would be keen to know exactly when you go into the red each month.

So far, this information - or data - is held by your bank. In the past, they may have been keen to sell you other products, such as overdrafts at a certain interest rate. Most people stay loyal to their bank. The Competition and Markets Authority (CMA) found that only 3% of personal customers move their accounts each year.

The theory of Open Banking, external is that such data is owned, not by the bank, but by the customer. He or she can share it electronically and get a better deal on financial products, such as getting a cheaper overdraft elsewhere.

A new set of EU rules will require banks, building societies and other financial providers to let customers easily and securely share this financial data with other banks and other regulated financial businesses.

The CMA told the nine largest current account providers to be ready by 13 January.

However, the regulator has since given a maximum of six extra weeks preparation time to Barclays, Bank of Ireland, RBS and HSBC. Santander-owned Cater Allen, a private bank that has 40,000 active business current accounts, will miss the deadline by a year, as it needs to rebuild its IT system.

Allied Irish Bank, Danske, Lloyds Banking Group and Nationwide are ready to start on time.

However, a change in the law means no UK bank and building society will be able to block a third party from accessing a customer's account, assuming the customer has given permission, unless they suspect fraud or unauthorised access.

How will it work?

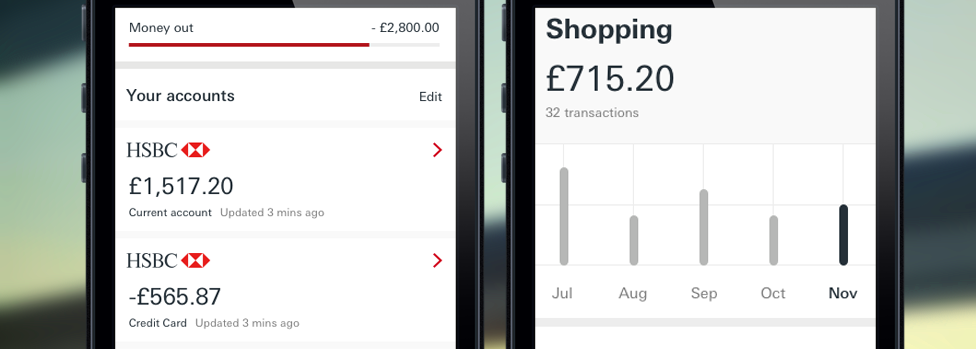

In practice and in time, customers will probably see a dashboard on their bank's mobile phone app.

This will show them how much money they have in their different accounts, with different banks, and eventually how much they owe on credit cards and store cards too.

They will also be able to switch on other services. So, a business separate to the bank might take money left over at the end of the month and invest or save it. Another may look at how much you spend on broadband and offer to switch you to cheaper deals. Another may spot unusual transactions from someone with mental health difficulties and alert a carer.

The customer could simply chose to give one of these apps access to their account information.

Crucially, these services will have access to the data, but will not have the login and password details to your account. A customer can switch off these services whenever they want.

A set of computer programming rules in the UK, called Application Programming Interfaces (APIs), will ensure all these new services and banks to talk to each other.

All of these providers will be regulated by the Open Banking regime under Financial Conduct Authority rules.

Open Banking in action

Examples of new services include:

Money management apps that give tips and advice based on how your current account is used

An app that monitors your balance and warns you if you are going overdrawn

Third parties, such as a price comparison websites, analyse spending patterns and recommend products based on this, such as a cheaper overdraft, or a better credit card

Source: Open Banking

What is the benefit?

The CMA's review of retail banking decided against capping overdraft charges, claiming that this Open Banking system will allow us to shop around and switch our current account provider more easily.

In time, this could be done with a one-click switch, it is said.

Applications for mortgages could be dealt with more quickly, as providers and brokers could access spending history, rather than ask for printed copies of the last three months of bank statements.

Anne Boden says the benefits could affect more than money

Early adopters say the benefits could extended beyond people's finances. Anne Boden, of mobile-only Starling Bank, says customers will be able to see exactly what they bought for lunch each day, an app could analyse the calorie levels, and then cross-check it with how much exercise that person is doing.

Tightening one's belt would be literal, as well as financial.

"This gives customers transparency and choice - something which the big banks have kept from them for too long," Ms Boden says.

What are the downsides?

Customers could be bombarded with invitations to try out a new service, and could quickly lose control of their financial data, according to Mick McAteer, of the UK's Financial Inclusion Centre.

He describes Open Banking as "a daft idea", which will lead to more financial exclusion for those already on low incomes.

There is a danger, he says, of these consumers being exploited, such as through businesses offering a new form of expensive payday loan.

Diane Coyle, economics professor at Manchester University, says: "I was, and still am, sceptical about how much people will want to give access to their financial information to third party apps, and surely the steady drip of stories about security breaches since the plan was announced won't have helped.

"It is hard to understand people's attitude to their data and security, though, as many cheerfully give loads of information to social media companies, but on the other hand were reluctant for the NHS to have access to their health data for research purposes."

Recent research by consultants Accenture found that 85% of those asked said the fear of fraud would put them off sharing data, and 69% said they would not share financial data with businesses that were not banks.

An open goal for fraud?

Unscrupulous individuals would be keen to access this data and use it alongside information revealed on social media to build up a complete set of personal information.

This could be used to rip off consumers if the system is not working well.

But organisers say that there are strict regulations and, unlike now, all this can be done without giving access to your bank's login.

If anything goes wrong and there is an unauthorised transaction, the customer's bank must refund the money and claim it back from the third party if the issue was their fault.

Customers can complain to a bank or a service provider about their service. They must respond within 15 days, or 35 days in the most complicated cases.

- Published28 September 2017

- Published9 August 2016

- Published1 November 2016