The perils of a political Federal Reserve

- Published

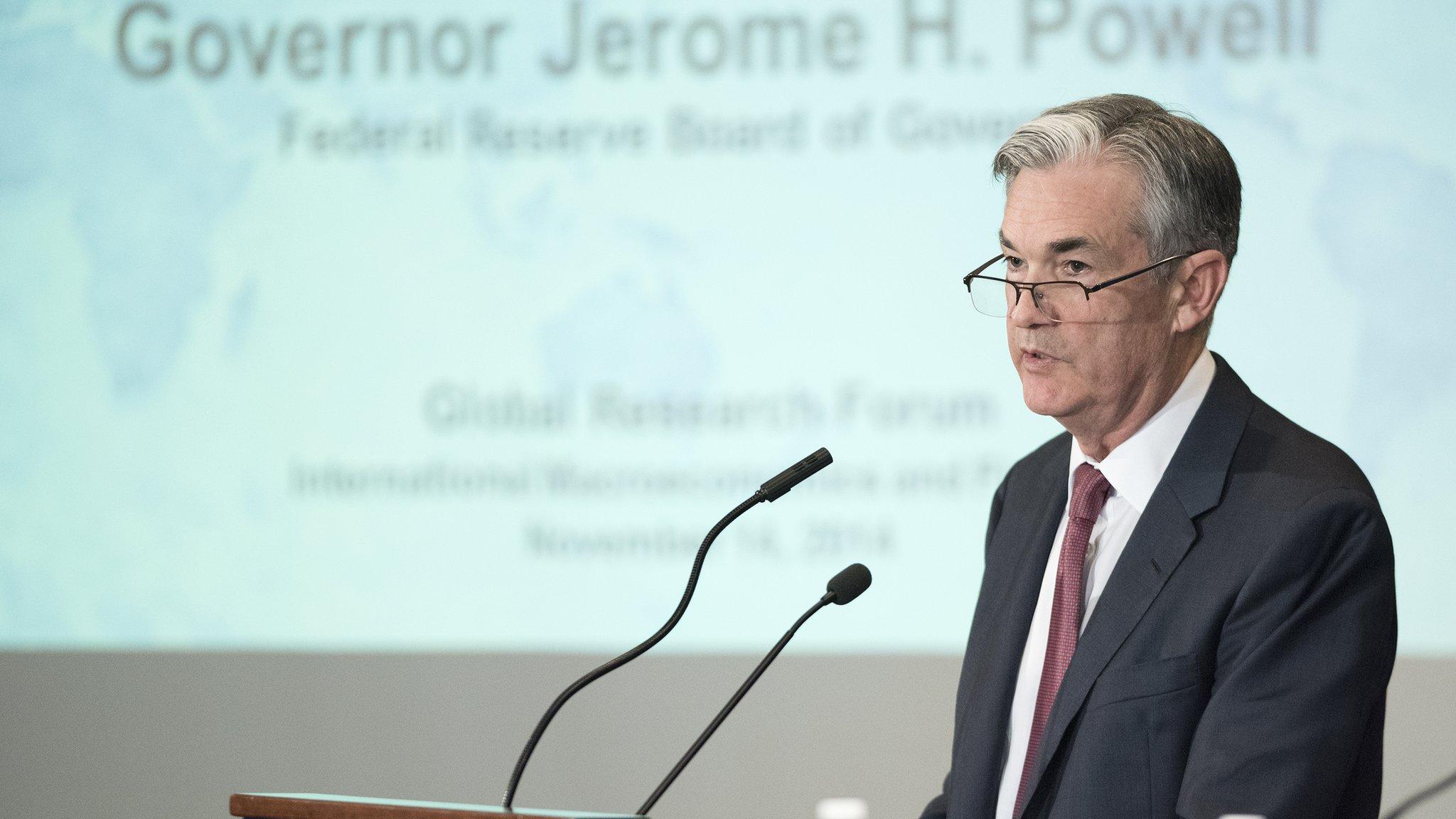

Jerome Powell was chosen by Donald Trump to chair the US Federal Reserve

"I respect his independence," said US President Richard Nixon. "However, I hope that independently he will conclude that my views are the ones that should be followed."

As threats go, it wasn't exactly subtle.

The year was 1970 and Mr Nixon had just sworn in Arthur Burns as chair of the US central bank, the Federal Reserve. At the same time, he was eyeing re-election in 1972.

Like those who occupied the White House before him, Nixon knew what voters cared most about was the economy.

Arthur Burns and Richard Nixon

But he had a problem: while the US economy was still in its post-war boom period, there were signs it might be growing too fast, or "overheating". Too much growth, too quickly, often leads to high inflation, which pushes prices up for everything from household goods to cars.

One way of containing inflation is raising interest rates, but this can slow down spending and put a pinch on those looking to get loans - something Mr Nixon desperately wanted to avoid in the months before election day.

Enter Mr Burns, the bespectacled economist chosen by the president to replace William Martin as Fed chair. Mr Nixon made no secret of his belief that Mr Burns should follow his directives, even though the head of the Fed is supposed to be free of political influence.

Richard Nixon resigned the presidency in the wake of the Watergate scandal in 1974

At the president's behest, Mr Burns cut interest rates just when they should have been increased, leading to a US economic boom ahead of the 1972 election.

While it helped get Mr Nixon re-elected, that boom then transformed into a toxic combination of stagnant economic growth and rampant inflation - also known as "stagflation" - that took decades to bring under control. (Mr Burns also served under presidents Ford and Carter until he stepped down from the Fed in 1978.)

Trump's 'mark'

The Nixon-Burns fiasco ushered in an age of relative independence at the Fed.

Although the head of the Fed - and members of its governing committee - are appointed by the US president and confirmed by Congress, there has been a broad consensus that the bank's interest rate decisions should be seen to be impartial.

But the 2008 financial crisis, and the extraordinary powers subsequently granted to the Fed - and other central banks - began to change this state of affairs.

President Trump broke with tradition by not re-appointing Janet Yellen to run the Fed

It's something that Donald Trump often touched on during his presidential campaign, when he was highly critical of the Fed, saying it was more political than his rival Hillary Clinton.

Once in office, in a break with tradition, Mr Trump opted not to renew President Obama appointee Janet Yellen's term at the helm of the Fed.

Instead he nominated lawyer and former investment banker, Jerome Powell, after expressly stating he wanted a Republican in the top job.

Mr Powell will be the first head of the US central bank without an economics degree in nearly three decades.

"We've had two other lawyers that have been appointed to chair the Fed, and both were very unsuccessful," says Burton Abrams, professor of economics at the University of Delaware.

Some have suggested Mr Powell's non-academic background could lead to a central bank that's more in touch with the needs of the private sector. But what has raised eyebrows beyond Mr Powell's background is the degree to which President Trump made sure it was known that Mr Powell was his pick.

Jerome Powell testifies at his Senate banking committee confirmation hearing last month

"You'd like to make your own mark," Mr Trump said in November, response to a question about why he did not intend to re-appoint Ms Yellen.

This has led many to speculate whether the president, who has extensive business holdings that could benefit from lower interest rates, could be angling to unduly influence the Fed.

"Donald Trump is fairly unique - certainly I don't recall any other billionaire becoming president, and he is a real estate developer, all heavily involved in banking and interest rates, so there is a strong economic tie," adds Prof Abrams.

'Stars aligning'

But Donald Trump is by no means alone. In the aftermath of the financial crisis, central banks across the world - from the UK to Japan - have become frequent targets of politicians from all sides.

In Japan, the early iterations of Abenomics were seen by some, including Germany's central bank head, as a violation of central bank independence.

And a recent survey, external of European economists found that for the first time, a significant portion thought that central bank independence in the UK and in the eurozone would decline in the next four years.

This comes despite a body of academic research showing that when a country has a politically independent central bank, inflation tends to be lower and prices are generally more predictable.

And in the US, in addition to Mr Powell, there are three other key vacancies open on the Federal Reserve's board - giving Mr Trump more ability than any president in recent memory to shape America's central bank.

Mr Powell has yet to take office, and a political appointment as chair does not necessarily mean a political Fed, but according to Prof Abrams, "you can see the stars are aligning for a repeat [of Nixon-Burns]".

And as the diaries of Arthur Burns attest, standing up to the man in the Oval Office when it comes to monetary policy is no easy task: "I knew that I would be accepted in the future only if I suppressed my will and yielded completely - even though it was wrong at law and morally - to his authority".

Follow Kim Gittleson on Twitter @KGittleson, external, and Joe Miller @JoeMillerJr, external

- Published2 November 2017

- Published6 December 2017