How changing coffee tastes are helping farmers

- Published

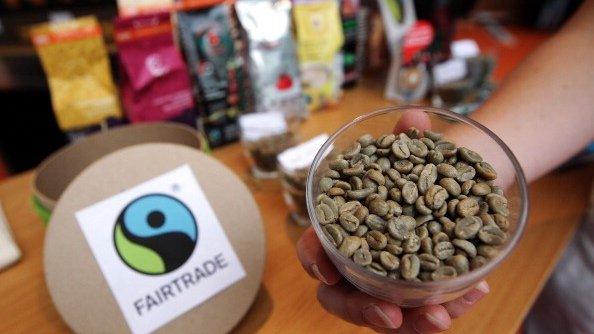

Consumers are increasingly willing to pay more for ethically sourced coffee

Would you pay more for your coffee if you knew exactly where it came from and how it got to you?

An increasing number of Western "millennial" consumers would, and it's benefiting everyone from the farmers who grow the beans to the artisan cafes selling the stuff, everywhere from London to Los Angeles.

The growing thirst for ethically produced, sustainably sourced coffee means farmers can be up to three-and-a-half times better off simply by selling their beans in the right way.

According to new figures from the UN's World Intellectual Property Organisation (Wipo), smarter processing, branding and marketing makes a huge difference to growers and their communities.

It means coffee drinkers like those at The Attendant, a cafe in trendy east London, know they can bring a sign on the wall to life. It reads: "Change the world, start with coffee".

The provenance of the coffee beans is a selling point for us, says Ryan de Oliveria

The cafe tries to make customers aware of the specific story of the beans that made their cappuccinos and lattes, as well as the impact they are having by choosing to drink ethically.

The Attendant develops relationships with individual farmers through green coffee traders so that they can carefully select beans from individual farms.

Technology helps ensure the beans can be tracked all the way from the farm to the cup. When I visited I drank a £3 ($4) cappuccino made from beans grown in the Rwenzori Mountains of Uganda - about 18% more expensive than the average price of a coffee in the UK. , external

However, the customers I speak to are happy to pay more than they might elsewhere if it meant the farmers were getting a fairer price for their beans.

Marketing executive Amy tells me "I do like to know that it's ethically sourced because you just feel better about drinking it".

The Attendant uses beans from the Rwenzori Mountains of Uganda

"It is important that the farmer gets a fair price for the coffee they sell," says logistics manager Eric, adding he also feels that consumers should be asking more questions about where their food comes from.

Ryan de Oliveria, the cafe's co-founder and chief executive, says there is "a large demand" for ethical sourcing that goes beyond just buying traditional labels such as Fairtrade.

One of their coffees comes from a particular farm in Uganda, a country not known for its coffee, but he says he has "managed to find a farmer who is growing some really good beans".

Mr de Oliveria says he tells all his baristas about the provenance of the coffee, so they can then tell customers.

"For example, there was a lot of warfare in Uganda and we talk them through the impact we are trying to make with those farmers to stabilise their communities."

The growing demand for coffee that does more than just perk you up has helped Ryan expand to three branches, as well as sell coffee wholesale and by subscription.

"People want to know that they are doing good and they don't want to buy something from a supply chain that is corrupt," he says.

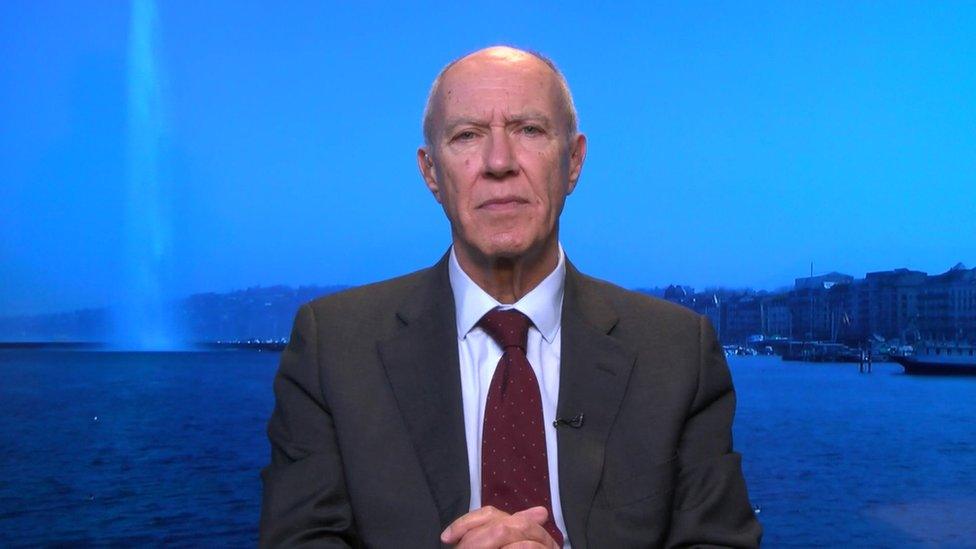

That sentiment is echoed by Wipo's director-general Francis Gurry.

Artisan cafes pay farmers a fairer price, says Wipo

He says the evidence shows that "ethical consumers, discerning consumers and farmers' interests can all come together to add value to everyone".

In practical terms, he says the extra income means a better quality of life for farmers and their families, but also "the possibility of investing or reinvesting more in their businesses".

Instant coffee represents by far the biggest share of the global coffee market. As with any coffee it needs to be roasted relatively near to the end consumer so that it maintains its taste until it is actually drunk.

That is why most of the margin added to the beans is pocketed near to where they are consumed, rather than where they are farmed.

The Wipo research shows that for a pound (454g) of beans that ends up on a supermarket shelf, the roaster can earn $4.11 (£3.07). But the export price, most of which goes to the farmer, is just $1.45 (£1.09).

"Ethical consumers, discerning consumers and farmers' interests can all come together to add value to everyone, " says Francis Gurry

Large western coffee chains account for the next largest segment of the coffee market. They typically add more value to the beans by serving them as different espresso-based drinks which are brewed by baristas.

The beans are often produced to the standards required for Fairtrade and sustainability certification. It means the roaster can get $8.50 (£6.37) and it's also better for the farmer and their community because the export price doubles to $2.89 (£2.16).

However, farmers do even better when artisan cafes are the buyers.

The roaster can get $17.45 (£13.02) and the export price climbs to $5.14 (£3.85). It's because consumers, typically western millennials in the US and UK, are prepared to pay more.

Small, independent cafe owners are not alone in noticing that coffee aficionados are prepared to pay extra for ethical drinks.

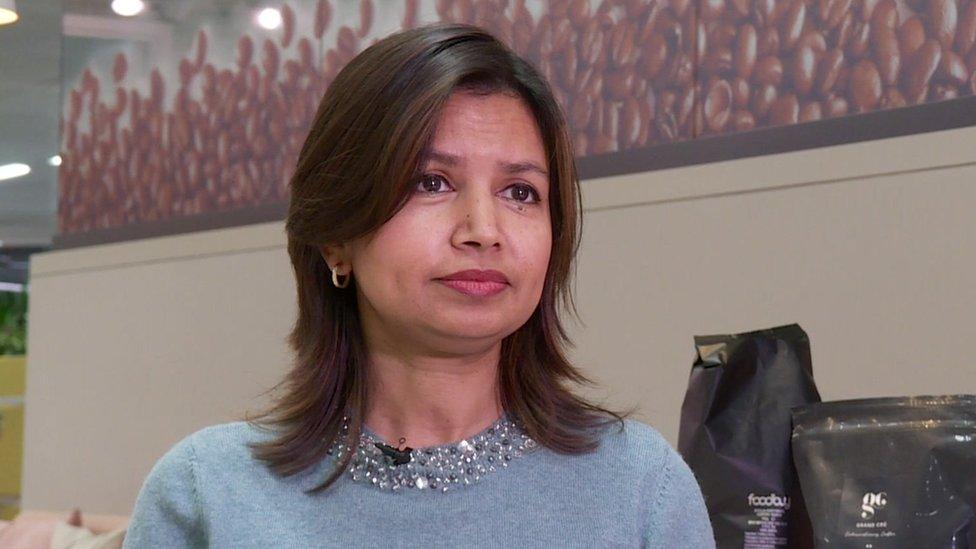

Established roasters don't want to be left behind by the new generation of coffee drinkers, says Kona Haque

Over the past few years the two companies that sell the world more coffee than anyone else, Nestle and JAB (whose brands include Douwe Egberts, Jacobs and Kenco), have continued to spend billions of dollars buying up artisan rivals, such as the Californian chain Blue Bottle Coffee.

According to Kona Haque, head of research at the commodities trader ED&F Man, they are using their cheque books to try and maintain their market shares.

"What we're seeing is that these newer, more ethical coffee companies have grown strongly from a small base," she says.

She adds that the more established roasters don't want to be left behind by the new generation of coffee drinkers who are embracing trends that started on the US west coast.

While consumers in developing coffee markets are happy to drink instant coffee, Ms Haque says the speciality end of the market is "high margin, high value" and there is profit to be made.

For Wipo's Francis Gurry it's a "win-win situation" because consumers get a higher quality product and "can enjoy the knowledge of the specificity of what they're consuming".

More importantly, he says, farmers in the developing world are getting a better share in the global value chain.

- Published3 August 2017

- Published27 February 2017