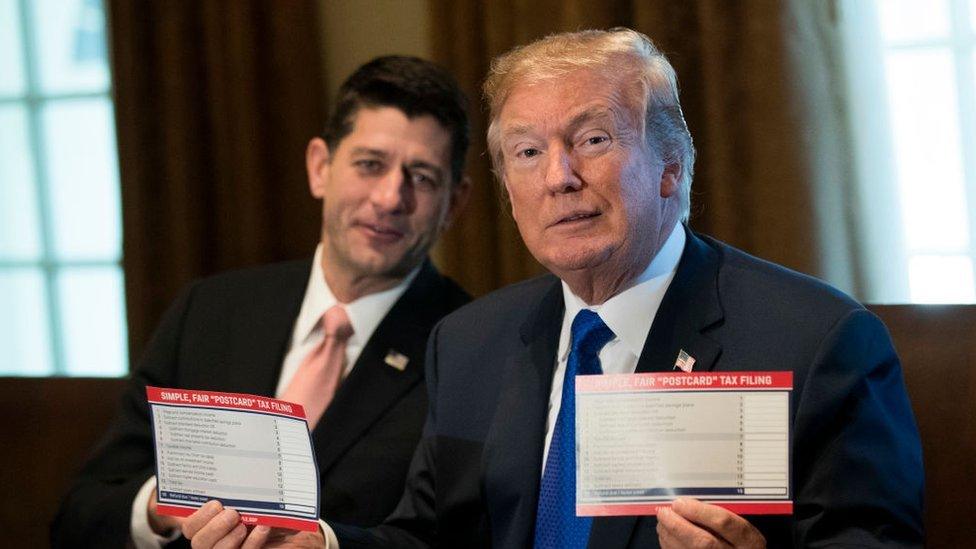

Will Trump's plans trigger a tax war?

- Published

The US may be about to set off an international tax war, as it moves to slash the corporate rate and overhaul the treatment of multinational firms.

The changes are aimed at making the US a more attractive place to do business, while reducing loopholes firms use to shield profits overseas.

But some of the new items - including a perk for exporters - may breach international rules and treaties.

European finance ministers have already voiced concerns, external about some of the plans.

The US is likely to face challenges to some measures and the combination of changes could pressure other countries to rewrite their own rules, perhaps by lowering taxes, said Reuven Avi-Yonah, a law professor at the University of Michigan.

"It's kind of turbulent waters ahead," he said. "The real question is, how will other countries react."

The US Congress is set to vote on the final version of the US tax bill on Tuesday, signing off on what will be the most sweeping overhaul of the tax code in a generation.

Tax attorneys have predicted it will take at least a year to understand the implications of the international changes.

"This stuff is not going to go down like chocolate sauce," said David Rosenbloom, an attorney at Caplin & Drysdale and a former tax official.

How is the plan aiming to make the US more attractive for businesses?

At the heart of the US plan is a reduction in the corporate rate from 35% to 21%. It also changes how businesses account for certain kinds of expenses.

Under the proposals, the US will also stop taxing the profits that American companies earn abroad - a change that brings the US into line with tax regimes in other countries.

Together, these measures would cost the US more than $1.4tn in revenue.

To offset the revenue losses, the US is imposing a one-time tax on profits held abroad, levied at 15.5% for cash and 8% for illiquid assets.

Depending on your perspective, the measure either captures tax that firms otherwise would have avoided, or provides companies with a major break on what they would have otherwise owed.

"Allowing them to pay a low rate is basically a get-out-of-jail halfway free card," said Matthew Gardner, senior fellow at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, a left-leaning Washington think tank.

Will this do anything to prevent companies keeping their profits offshore?

To discourage unfair profit-shifting in the future, the US is imposing a new minimum tax of about 10% on global intangible income - such as patents - and toughening rules related to payments to foreign subsidiaries.

Those provisions are expected to hit pharmaceutical and technology companies, which currently avoid taxes by booking profits attributable to technology in low-tax jurisdictions.

But it is not clear how effective the rules will be.

Will the US tax code end offshore tax breaks?

Analysts said the provision might encourage firms to move important "tangible" investments, such as factories, abroad, since the bill exempts some of the profits gained from these from tax.

Because the minimum tax is calculated on a global basis, it also does little to counter the appeal of tax shelters, they said.

"I don't see this as raising tax burdens for very many, especially by the time this all gets through," said Kimberly Clausing, a professor of economics at Reed College.

Tax attorney Robert Misey, who leads the international department at law firm Reinhart Boerner Van Deuren, said he thought there might be opportunities to circumvent the new levies.

And, he noted, some of the provisions apply to companies with more than $500m in revenue over three years - those that can most afford savvy tax advice.

"Let's face it," Mr Misey said. "Those are the companies that are going to try to figure out every angle to avoid it."

Will this lead to a tax war?

The bill allows US companies to claim a deduction for money earned from exports, in effect lowering the rate on exports to about 13%.

That change is likely to be seen as an illegal subsidy by the World Trade Organization and could lead to challenges.

"I would expect foreign countries to be somewhat aggrieved by this statute," said Caplin & Drysdale's Mr Rosenbloom, who added that policymakers were using the US tax plan for "isolationist" goals.

The new plan also increases the tax liability of US subsidiaries that make payments to foreign firms. That measure has companies in places such as Germany, external worried.

Prof Clausing said she thought those rules were vulnerable to challenge - or negotiation - and could be designed to strengthen the hand of the US in international discussions about taxes.

"Many people view that as a more of a political gambit," she said.

- Published19 December 2017

- Published13 December 2017

- Published2 December 2017