World trade: What will Donald Trump do?

- Published

What trade policies will Donald Trump adopt when it comes to China?

Of all the questions hanging over world trade this year, none loom bigger than President Trump.

For decades, the US was the biggest driving force behind moves to stimulate more international trade.

Now it's the most important sceptic.

So for 2018, the big question has to be: what can we expect from him, and other forces around the world that share his doubts about trade?

Confrontational again?

Perhaps the biggest single issue looking ahead is President Trump's hints that he might revert to his previous more confrontational approach to trade relations with China.

A container ships loads up in Qingdao, China: Seven of the world's 10 busiest ports are in China

During the election campaign Mr Trump spoke aggressively on trade, about US agreements and about some of the country's trading partners.

He made an early start on his agenda after taking office. One of his first acts was to withdraw the US from a trade agreement that had not come into force, the Trans-Pacific Partnership.

He has started the renegotiation of another, the North American Free Trade Agreement (Nafta) with Canada and Mexico that took effect in 1994, although he has so far stopped short of earlier threats to pull out of it altogether.

Another proposed agreement that was under negotiation between the US and the European Union has gone into the deep freeze, perhaps permanently.

The Mexico-US border, San Diego, California: Mr Trump has started to renegotiate the existing Nafta trade deal

He also has serious doubts about the World Trade Organization. The United States' lack of enthusiasm was a central factor behind a lacklustre outcome at the WTO's conference in December.

It ended without new deals or even the usual agreed declaration of commitment to the system that the WTO manages.

Historic contrast

It is a striking contrast with the previous 70 years.

GATT, among with institutions such as the IMF and the World Bank, was one of the pillars of the post-Second World War world

Since the late 1940s the trend has been one of reducing or removing barriers to cross-border commerce. The global effort took place first with the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (Gatt) and then the WTO, which started work in 1995.

There has also been a proliferation of agreements between smaller groups of countries that provide deeper trade integration than the WTO.

The underlying idea was to avoid a repeat of the trade barriers that were erected in the 1930s, barriers that probably aggravated the Great Depression (though they were not the original cause of it).

Trade barriers are now widely seen as having worsened the 1930s Great Depression

There was also the idea, with strong roots in economic theory, that stimulating trade by reducing barriers to it would make all countries better off.

That said there is also plenty of economic analysis that suggests that some people within countries lose out. It's just that the gains are reckoned to exceed the losses.

Mr Trump represents a striking contrast to this approach.

He appears to believe that if you have a trade deficit - if you import more than you export - you are losing out. He looks at both the overall trade balance with the rest of the world and the bilateral balance with particular countries.

Workers on Ford assembly line: Mr Trump believes the US has lost jobs to countries like China

He is especially irked by the hefty deficits in US trade with China and Mexico, among others. He also regards trade as the cause of lost jobs in US industry.

All these points are controversial.

Economic theory

Most economists regard trade deficits and surpluses as being driven largely by saving and investment decisions.

President Trump sees US trade deficits as evidence that the other country is trading unfairly

A country where investment is more than national saving has a trade deficit (strictly speaking it's the current account of the balance of payments which is in deficit - that's trade plus some financial transactions, including profits and income sent across international borders).

A large imbalance in the overall current account can certainly be troubling and has sometimes been a precursor to financial crises. But most economists think it makes much less sense to worry about individual bilateral deficits.

President Trump sees the deficits as evidence that the other country concerned is trading unfairly or that US policy in the past has been weak.

President Trump and China's Xi Jinping: The biggest bilateral trade deficit the US has is with China

Many economists would also argue that trade is not the main cause of industrial job losses. Certainly there are many who agree it has contributed, but technology is thought by many to have had a bigger impact.

President Trump's approach to that has moved over time.

Before he became president he threatened a 45% tariff on Chinese imports, yet in his first year in office he has been much more restrained in part out a desire for Chinese cooperation in dealing with North Korea.

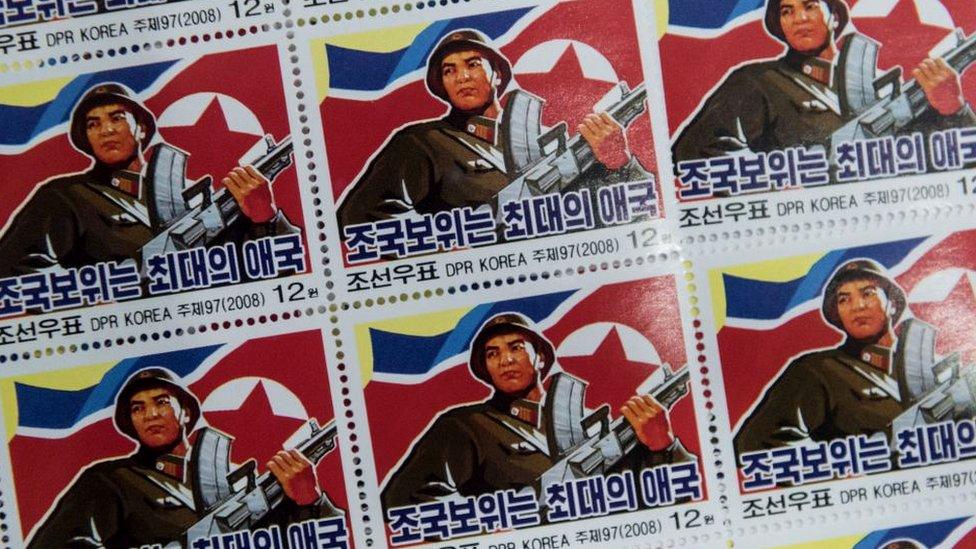

But now he is unhappy with China, accusing Beijing of allowing oil to go to North Korea in breach of international sanctions.

US attitudes towards China are linked to the question of how best to deal with North Korea's nuclear ambitions

So there is a renewed possibility of serious trade conflict between the world's two largest economies.

Global Trade

More from the BBC's series taking an international perspective on trade:

International trade had already had seen some setbacks even before Donald Trump's arrival on the scene. It has been growing more slowly than it was before the 2008 financial crisis.

Over the preceding quarter of a century or so, the average growth in global trade was about 6%. In the last ten years it has been around half that, though it did pick up to 4.2% in 2017.

Brexit's impact

Looking beyond 2018, the pattern of world trade may also be affected by Britain's departure from the European Union.

The UK's Brexit Secretary David Davis: Depending on how UK-EU arrangements are finalised, Brexit could affect global trade

The referendum vote to leave does in part fit into the wider picture of resentment about the consequences for globalisation - though in the UK case it was more about migration than trade. Indeed the government implementing the referendum result is enthusiastic about trade seeing Brexit in terms of new global opportunities.

That said there could be a trade impact, if there are new barriers to commerce between the UK and the EU.

2018 looks like being an important year for global trade. Seventy years of increased global openness to trade won't be reversed, but it is certainly facing new challenges.