The strange marriage of toys and the big screen

- Published

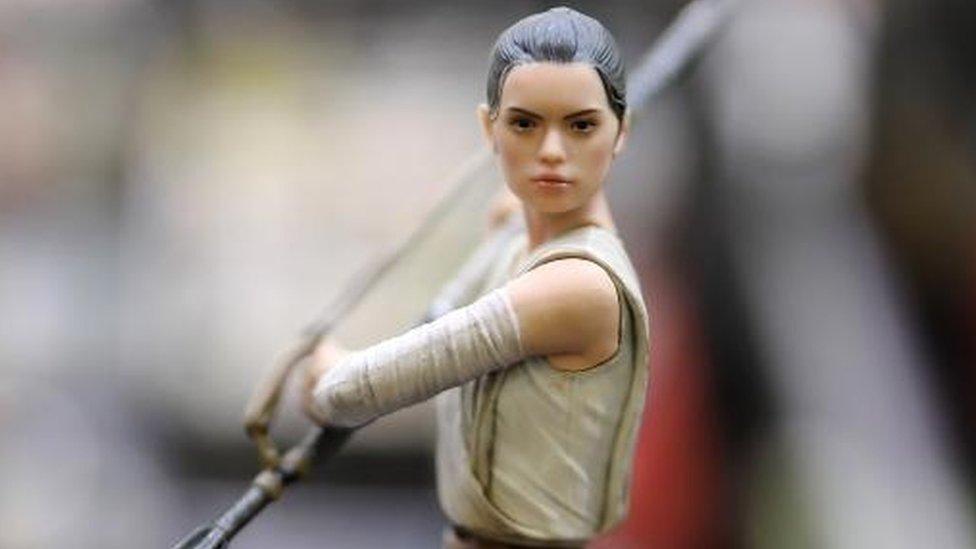

Star Wars was a success for the toy industry too

Parents may wish that their children turn off that device, just for a minute, and play with some proper toys.

A recently-published survey of parents found that three-quarters of those asked thought excessive screen time would make their children less sociable in later life.

The majority are worried about the health effects on an inactive child.

The toy industry recognises parents' wishes and is making games aimed at stimulation and traditional play. Yet, the industry's relationship with the screen - big and small - is so important that the industry actually relies on children watching the blockbusters on the internet, film or TV.

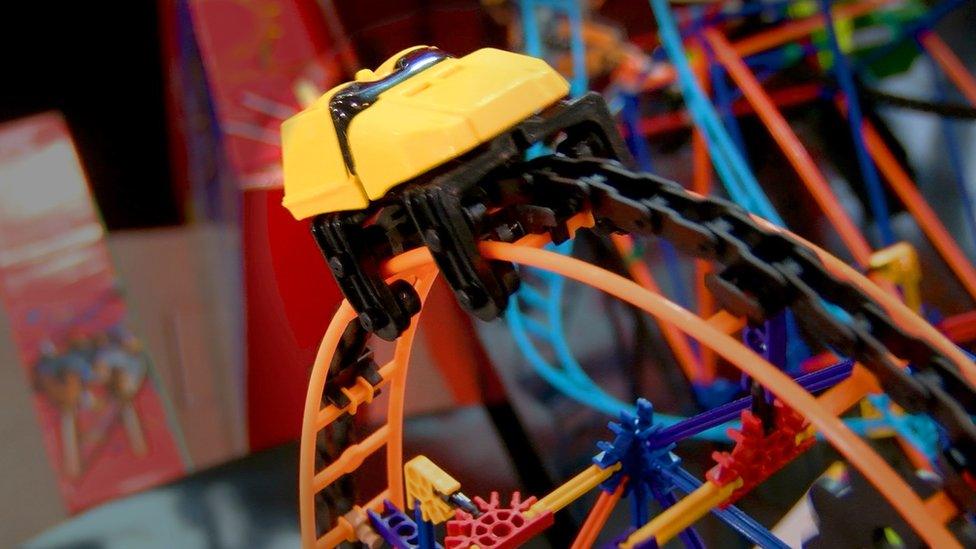

WATCH: The toy rollercoaster you can ride

Last year was a difficult one for the UK's toy industry. Sales fell by 2.8% compared to the previous year, to £3.4bn, according to the British Toy and Hobby Association and analysts NPD, following three years of consecutive growth.

One of the key reasons, they say, was underperforming licences.

Licences account for a quarter of the total toy market, according to Frederique Tutt, global industry analyst for the NPD Group's toy division.

A licence-holder of a major film or TV show will invite bids from toymakers for some or all of the toy spin-offs from the movie. In return, the licence-holder will receive upfront promises and a percentage cut from sales.

In numbers: The British toy market

More than 26,000 new toys launched

Collectable sales up 17% - the big hit of the year

£339 spent on toys for the typical child aged up to nine

£9.70 - the average price of a toy

Online sales account for 37% of the market

Fourth-largest market in world after US, China, and Japan

2017 figures

The last "gigantic" licence was Star Wars, says Ms Tutt. Manufacturers knew it would be a blockbuster hit in the cinema and have broad appeal.

"The products were popular with regular toy consumers, but also adults and collectors," she says.

Big toy companies will spend a lot on the licence for a guaranteed cinema blockbuster, but the golden egg is winning the rights to produce toys linked to an unexpected hit on the big screen.

Last year was one of missed opportunities, Ms Tutt says, with some of the biggest cinema hits failing to have much toy merchandise linked to them.

Children's changing habits were also important. Instead of pestering their parents to go to the cinema, they were watching their peers play with collectables and unwrapping toys on internet channels such as YouTube. They were the big success story of 2017.

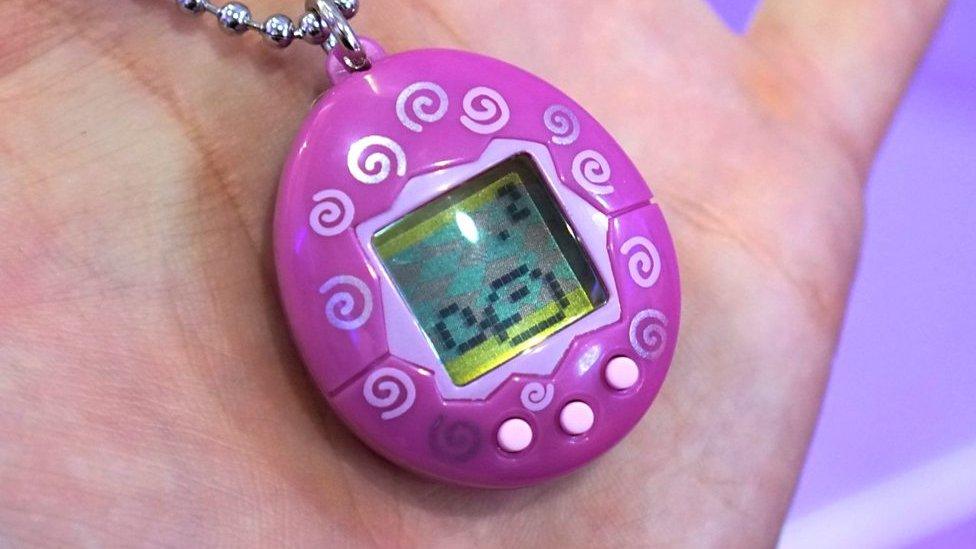

WATCH: Tamagotchi plans tiny UK comeback

Some of the big toy manufacturers pay big money for licences, and their stalls dominated the floor of the annual UK Toy Fair that has been taking place this week.

Yet, tucked away in some of the quieter corners of the vast halls of London's Olympia was evidence of the other end of the UK's toy industry.

Leeson George is a carpenter who invented a game during a party in his shed in Stockwell in south London.

The 32-year-old and his friends had transferred the celebrations to the garden shed so not to disturb their neighbours. Once inside, he found himself pushing tealights across a table.

The tealights were lit at first, but the melting wax did not help their trajectory, he jokes, but his absent-minded play sparked an idea for Push It.

The tabletop travel game is a cross between bowls and shove ha'penny, where players aim to get their discs closest to the jack. He hopes it will appeal to competitive youngsters and pub game players.

He raised some money from funding platform Kickstarter, found a manufacturer in China, and says he has learnt a lot about pricing and even the size of packaging along the way.

Now the big challenge is to get the game selling in big stores, while still holding down his carpentry job.

In another sign of simplicity battling big money, the winning element for some games may become obvious - and it has nothing to do with brands or licences.

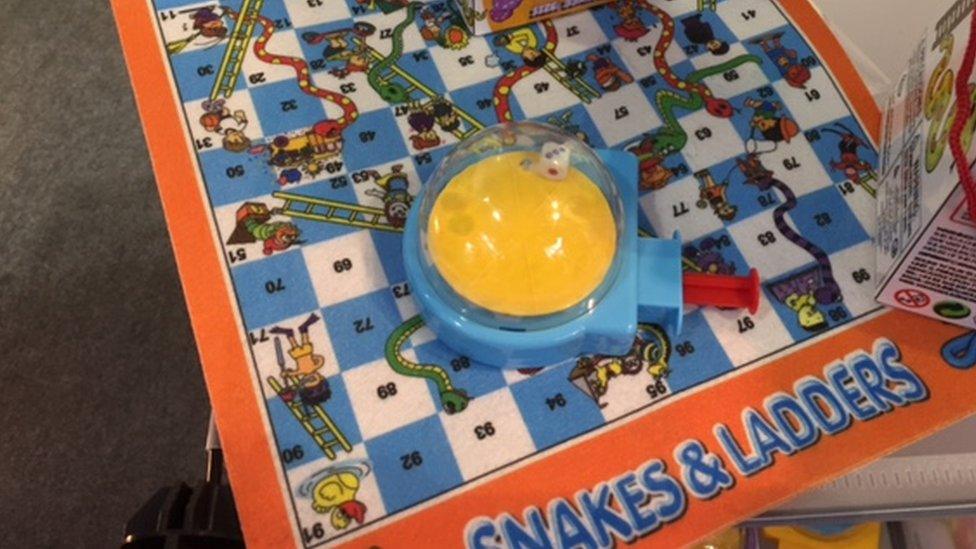

Christine Lawson, managing director of Eduk8, which designs and manufactures educational toys, says that one of her company's big successes is a snakes and ladders game.

The new element, that appealed to teachers particularly, is the inclusion of a dice dome. Players press a button to automatically roll the dice inside the dome.

It makes it a lot more difficult to lose, unlike a dice on its own which would often disappear behind a bookshelf, bringing a premature end to the game, she says.

The company's ambition is to create toys and games of educational value, and it uses educational psychologists to design their ranges.

"You have got to have toys that will engage children. They must be visually attractive, durable, and capture their interest," Ms Lawson says.

For that, she says, there is no need for a screen.

- Published24 January 2018

- Published25 January 2018

- Published21 December 2017

- Published24 January 2018

- Published8 November 2017