China Anbang crackdown: Who might be next?

- Published

Airlines, football clubs, five-star hotels and film studios.

China's biggest conglomerates have been snapping up businesses around the world, including some in fairly sexy sectors.

Despite growing so big and borrowing so much, they were seen as untouchable because of their political connections.

That was until the middle of last year when, after seemingly unrestrained growth, Beijing suddenly turned up the heat on some of those giants.

And then last week, some real action. Beijing cracked down on one of those firms - taking control of insurance and financial giant Anbang, and prosecuting the firm's head.

This, analysts suggest, could indicate more intervention is on the way.

HNA owns Hainan Airlines

Who might be next?

The move against Anbang was called a "warning shot" by the Economist Intelligence Unit.

But it is just one of the businesses which became known as "grey rhinos" - large, visible problems in an economy which are often ignored, until they start moving fast and trampling everything in their wake.

And next in Beijing's crosshairs, analysts predict, is likely to be HNA, which has been described as the biggest company you've probably never heard of.

Investing an estimated $40bn (£28.7bn) in the past three years, it differs from Anbang having primarily bought into "real businesses" rather than being built mainly around complex financial structures.

It owns China's Hainan Airlines, airport services firm Swissport, airline caterer Gate Gourmet, holds a major stake in Deutsche Bank, has a 25% share in the Hilton hotel group, and owns Carlson Hotels, which runs the Radisson chain.

While there's no suggestion it's in financial difficulties, expect Beijing to lean on HNA to get rid of "most if not all of its financial sector holdings", says Michael Hirson of analysts Eurasia Group.

Earlier this month, HNA said it had reduced its stake in Deutsche Bank from 9.9% to 9.2%.

While most of Anbang's investors were individuals putting cash into things such as insurance policies, HNA's backers are mainly institutions.

On the one hand, this would mean its collapse would be far less politically sensitive. The common man or woman on the street rarely sheds tears when financial giants get their fingers burned.

But Eurasia Group says we should not expect a too punitive approach from the government.

"Beijing is reluctant to impose major losses on bondholders, which would make it more expensive for many other Chinese corporates to obtain external financing," Mr Hirson said.

Significant bankruptcies would also carry political risks.

HNA hasn't commented. But speaking last year to the BBC, chief executive Adam Tan was sanguine about plans by Beijing to tighten restrictions on Chinese businesses spending money abroad.

He predicted HNA would still get support from Chinese banks, and could count on international banks as well because of its large presence outside of China.

It seems unlikely he will feel so secure today.

Dalian Wanda controls the AMC cinema chain

What about Dalian Wanda?

Of all the Chinese firms facing a crackdown, Dalian Wanda has the highest profile overseas, partly because of the sort of investments it made.

Run by Wang Jianlin, among the country's richest men, it grew into one of the country's most prominent property developers.

And it invested overseas too, most noticeably in Hollywood - controlling the AMC cinema chain as well as Legendary Entertainment, co-producer of hit films such as Godzilla and The Dark Knight Rises.

But Mr Wang, once considered a Beijing favourite, fell foul of the establishment, with lenders told to pull out their backing.

And after the warnings came he was quick to offload businesses, including theme parks and hotels in one of China's biggest property deals as it focused on its core shopping mall and cinema businesses. A subsequent rejigging of the deal just added to the picture of chaos.

Earlier it had pulled out of a $1bn bid for Dick Clark Productions - the owner of the Golden Globe TV and film awards - with China's clampdown on overseas investments blamed.

Michael Hirson of Eurasia Group described the asset selling as "aggressive moves" to "de-risk".

They were, he added, "a painful decision for Wang but one that now looks very astute".

Football club Wolverhampton Wanderers is one of Fosun's overseas investments

Who else is in the spotlight?

The other big player put on the watch list in mid-2017 was Fosun.

It has investments in the English football club Wolverhampton Wanderers, leisure group Club Med, travel firm Thomas Cook and entertainments business Cirque de Soleil.

And unlike the others, is still buying abroad.

Just last week, it said it had completed a deal to become the majority shareholder in Lanvin, France's oldest surviving couture label. Though by its standards, the investment of about $120m is fairly small.

Both Wanda and Fosun "appear to be on more solid political ground", according to Mr Hirson.

What does this mean for Chinese overseas investment?

The clampdown is very much aimed at the large conglomerates buying into a huge range of sectors.

Most other firms are able to keep investing.

But there has been a fall from the peak years of 2015 and 2016.

The number of Chinese deals in the US and Europe fell by almost 25% in 2017 from the previous year, Dealogic said.

And the rhetoric against Chinese investment in the US from the Trump administration - as seen in the collapse of some major deals - means this trend is likely to continue.

Just this week, Germany said it would be watching closely after Geely snapped up nearly 10% of Mercedes-Benz owner Daimler.

Why was Anbang targeted?

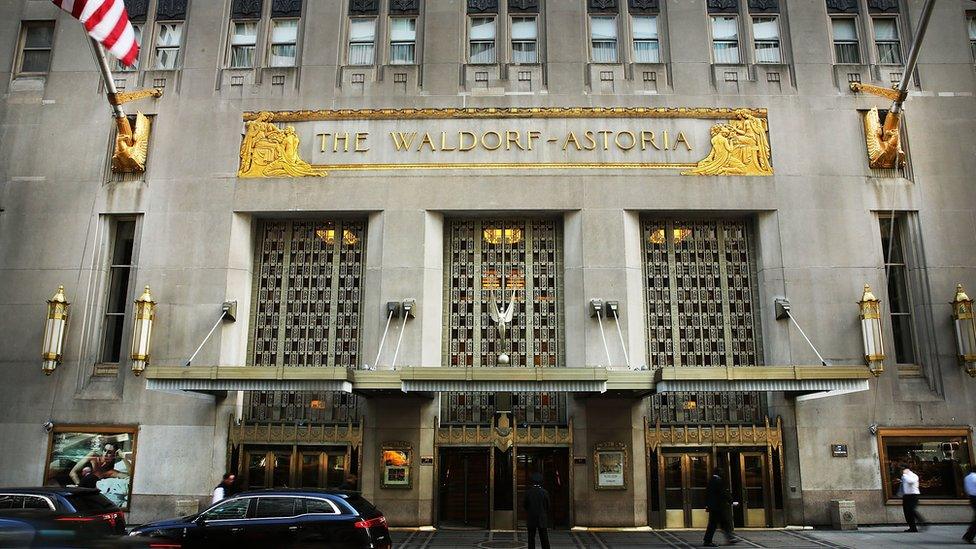

To recap from last week, Anbang firm was known for its aggressive international acquisitions, including New York's Waldorf Astoria hotel.

But Chinese authorities have been cracking down on the financial industry to guard against excessive borrowing and risk.

The firm's head Wu Xiaohui, who was already detained by authorities last June, is to face prosecution for "economic crimes".

Analysts at Eurasia Group described it as "both a takedown and a bailout".

"Beijing's approach reveals President Xi Jinping's approach to cracking down on conglomerates - punish wrong-doing by executives while sending a reassuring message to the markets," said Eurasia Group's Michael Hirson.

Anbang bought the Waldorf-Astoria for close to $2bn

China could have nationalised Anbang instead (as, for example, happened during the UK banking crisis in 2008 with Royal Bank of Scotland).

Or it might have forced its sale to another company (continuing the UK analogy, look at how HBOS was sold to Lloyds Banking Group).

Instead it put it under the stewardship of China's insurance regulator for one year.

This, notes Mr Hirson was a "relatively transparent and investor-friendly" approach, allowing the regulators to sell-off Anbang assets and bring in funds while keeping it out of state ownership.

- Published23 February 2018

- Published26 July 2017

- Published22 June 2017

- Published14 June 2017