Sexual assault: Can wearable gadgets ward off attackers?

- Published

Alexandra Ceranek thinks her Safe Shorts prevented a violent sexual assault

There are a growing number of gadgets and apps on the market which aim to help keep women safe from sexual harassment and attack. But are they effective or could they merely reinforce the image of women as victims?

It was five o'clock in the morning. Alexandra Ceranek was cycling through "a lonely industrial area" on her way to work as usual.

"I'm a saleswoman and I have to start my work very early in the morning," says the 48-year-old from Oberhausen, Germany.

"Two men were standing there," she recalls. As she cycled past, one of them attacked her, grabbing her backpack and pulling her down off the bike and onto the ground.

As she lay there in terror expecting a sexual assault, she kept saying to herself: "Pull the cord, Alex! You have to pull the cord!"

She was wearing a pair of undershorts that incorporated an alarm activated by pulling on cut resistant cords made from the same material as bullet proof vests.

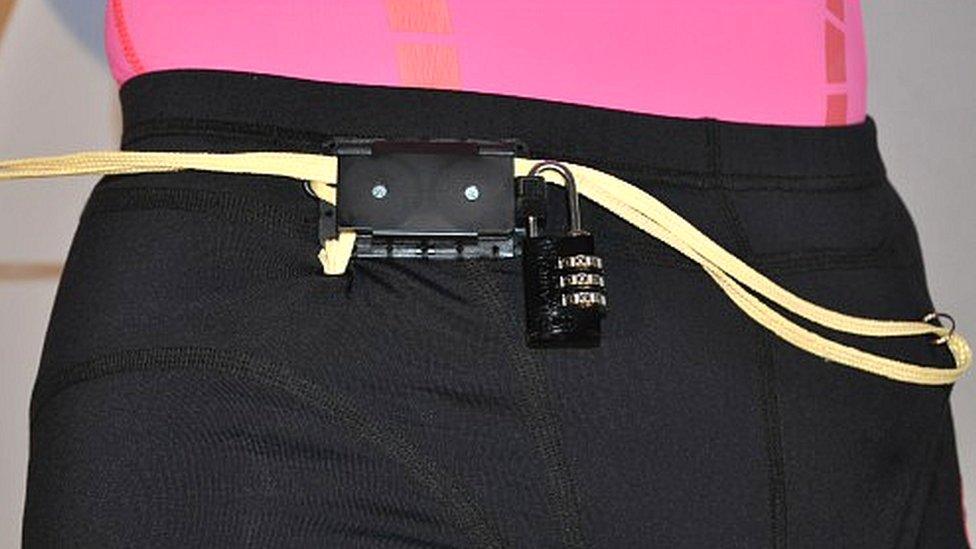

Safe Shorts are designed to withstand forced removal

"My heart was beating wildly, but I managed to pull the cord and set off the alarm," she says. "It made such a loud noise the two men ran away."

These Safe Shorts incorporate a lock and alarm that also activates when someone tries to remove the garment by force.

Safe Shorts founder Sandra Seilz says her own experience prompted her to develop the product. Returning from a run she was accosted by three men, she says, one of whom tried to pull off her leggings while the other held her down.

"You can imagine what the intention of the third man was," says Ms Seilz. "But I was lucky. A man set his dog on them and the three men ran away."

Sandra Seilz was prompted to develop Safe Shorts after being assaulted by three men

Assaults such as these are all too common for many women around the world, prompting many companies to come up with personal gadgets aimed at warding off attacks and alerting others.

"Vendors usually come from a crowdfunding background typically with very similar product functionality," says Rishi Kaul, a research analyst for consultancy Ovum.

"You click a button on the device and your GPS location is sent to preselected contacts, sometimes with an accompanying siren."

For example, Safer, developed by Indian start-up Leaf Wearables, sells a pendant that doubles as a panic button. It is controlled by an accompanying smartphone app.

Tanya Gaffney, 24, found it useful when walking to meet a friend in New Delhi, India, one evening.

Safer has developed a smart pendant that doubles as an alert service

"I felt someone walking behind me and it just felt suspicious. Every lane I turned into he took the same turn which made me panic," recalls Ms Gaffney. "I was hoping to find a female figure or cop."

But nobody was around.

She sent an alert to her chosen group of "guardians" - her parents and two close friends - by pressing the back of her smart pendant twice.

"Luckily, the first person to call me was my friend who I was on my way to meet at the market. He told me he was tracking me via GPS and that he was on his way to get me," she says.

The man following her eventually took a different turn, but "the feeling of panic still terrorises me to this day," she says.

Nimb co-founder Kathy Roma was the victim of a serious violent assault

Nimb's smart ring is actually a panic button and alert service

Similarly, Nimb is a smart ring incorporating a panic button that sends an alert and your location to chosen recipients. The alert can also be forwarded to the emergency services.

Nimb co-founder Kathy Roma was also a victim of crime 17 years ago. A man tried to strike up a conversation with her and stabbed her in the stomach when she didn't reply. Seriously wounded, she looked for help in a nearby building. She believes having a personal alert device would have brought help sooner.

Other devices include Revolar, which enables users to "check in" and let loved ones or friends know you've arrived home safely with a single click. Three clicks sends a "help" alert.

And at the more sophisticated end of the market, Occly has developed Blinc, a wearable security device that includes a "bodycam" to record video evidence of an attack, as well as setting off a siren, flashing lights and a call for help.

Meet the woman teaching others how to fight off sex attackers

According to the World Health Organisation, about one in three women have experienced some form of assault, whether physical, sexual or both. And nearly two-fifths of murders of women are perpetrated by their partners.

These safety gadgets have obviously helped some women avert disaster, but not everyone is convinced of their merits.

"We welcome anything that can be used to improve safety and help prevent sexual violence," says Fay Maxted OBE, chief executive of The Survivors Trust, an umbrella agency for 130 rape and sexual abuse support services across the UK.

"But such technology can also be misused - it can be hacked or used by perpetrators to track or stalk someone," she warns.

More Technology of Business

And Ms Maxted also worries that products such as Safe Shorts could "play on the fears a woman might have about being out on her own, rather than making her feel safe. They reinforce the image that a woman is unable to protect herself.

"Why should women have to wear clothes that are locked?" she asks.

But as far as Alexandra Ceranek is concerned, her Safe Shorts prevented an assault from developing into something much worse.

"I want a protection when there is a critical situation and someone wants to attack me," she reflects.

How data is being used to help monitor crime in Rio de Janeiro.

Ovum's Rishi Kaul thinks women's safety wearables will remain a niche market, particularly since there are now plenty of smartphone apps offering similar functionality, some that can be triggered by a scream or simply by shaking the phone.

"Women's safety wearables account for just 3.5% of the total wearables market," says Mr Kaul. "This function can simply be replaced by a safety app on the phone, which is why there hasn't been much success in this niche."

But for Ms Maxted, the issue of women's safety is more about education than technology.

"What technology solutions are there to teach potential abusers about consent and respect for women?" she asks.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external

Click here for more Technology of Business features, external