Is boasting good or bad for business?

- Published

Are, with a population of just 5,000, has become a Swedish start-up hub

Sweden is one of the most innovative countries in the world, yet has a business culture that discourages bragging about its success.

So is this humility a help or a hindrance when it comes to start-ups?

From household names such as Spotify and Skype, to gaming leaders King and Mojang and cashless payment companies iZettle and Klarna, Sweden is a hotspot for industry-changing new technologies.

Despite just 10 million inhabitants occupying a land mass largely defined by forest wilderness, the Nordic nation has in recent years created more billion dollar companies per capita than anywhere else outside Silicon Valley.

Last month, Sweden was top in Europe in Bloomberg's global innovation ranking.

The more familiar narrative for Sweden's start-up success story typically touches on several factors. It has a strong digital infrastructure, a highly educated, tech-savvy workforce, and an ideal population size for testing new innovations.

And for those whose ideas don't take flight, there is a strong social welfare net to set them back on their feet.

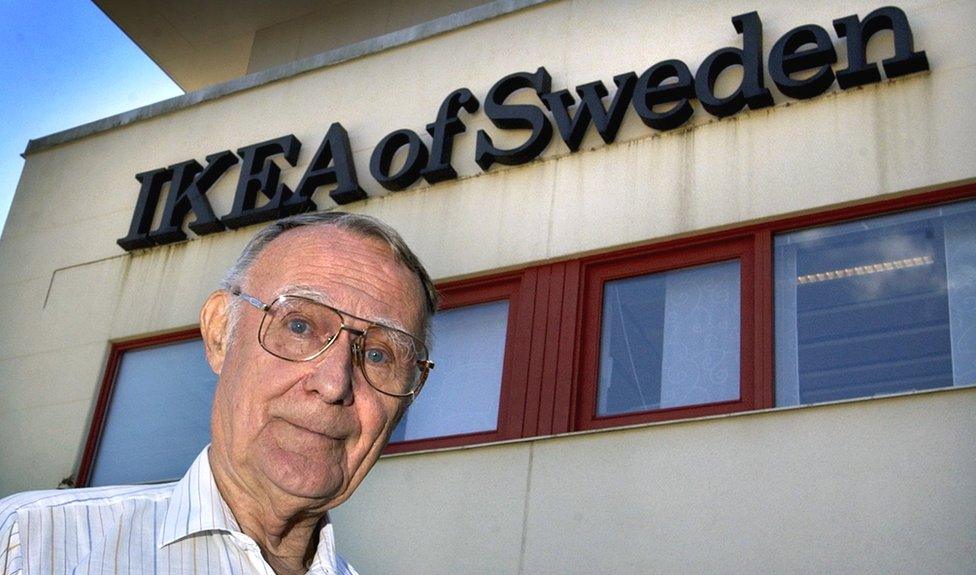

Billionaire Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad was known for his modest lifestyle

But since the death of Ikea founder Ingvar Kamprad - and obituaries highlighting his humility and frugality - these firmly-embedded cultural traits have recaptured attention.

Local and global observers are questioning their continuing role in shaping Sweden's thriving economy - including its disruptive tech scene.

"Trying to keep boasting to a minimum and finding a consensus so that everybody is on the same page" remain two of the most pervasive practices in the Swedish workplace, says Lola Akinmade Akerstrom, a former programmer and now a cultural commentator, who highlighted this in her recent book Lagom: The Swedish Secret of Living Well.

While the language in other innovation hubs might focus on individual rockstar CEOs "killing it"; in Swedish businesses "it's about everybody getting together, making sure their voices are heard equally, so that they can all reach an optimal solution together," she says.

At least part of this consensus-based culture has its roots in what Swedes call 'Jantelagen' (the Law of Jante) which draws its modern name from a town called Jante depicted in a 1933 novel by Danish-Norwegian author Aksel Sandemose.

This describes a centuries-old tradition that discourages extravagant displays of wealth or success and deconstructs hierarchies. In other words, nobody should consider themselves better than anyone else.

"In the workplace, Jantelagen creates a more collaborative, as opposed to a more competitive, environment because it's trying to remove all the stress points of competition or feeling like you're better than each other," explains Mrs Akerstrom.

Ulrika Viklund and Andreas Eriksson founded a community for entrepreneurs in the mountainous town of Are

About 400 miles north of the Swedish capital, the concept is being discussed over strong cups of coffee on the minimalist wooden benches and soft bean bags inside House Be, a co-working space and membership club for outdoor-loving tech workers in the mountainous town of Are.

Despite a population of just 5,000, Are has the highest proportion of young entrepreneurs in the country, according to the Confederation of Swedish Enterprise (Svenskt Naringsliv), with many people drawn by opportunities to spend time on the slopes or out hiking, while also building a business.

The hub was co-founded by Spotify's former international growth manager, Ulrika Viklund, who argues that the most positive aspect of Jantelagen in the start-up scene is that it encourages people to "help each other out more".

"We usually don't have this big boss that sits in a corner office and take all the decisions," she explains.

"At Spotify it wouldn't have been possible to succeed without this working culture where all the competences in the company are utilised because everyone is allowed to be innovative and say what they believe is the right thing to do."

Entrepreneur Johan Formgren is working on his fifth business

Johan Formgren, a tech entrepreneur previously based in Berlin, adds that Sweden's penchant for flat structures and modesty also helps to create strong networks.

"In Stockholm I was part of a network called SUP46 that gave us a lot of access to the biggest, greatest Swedish tech companies. The founder of Skype was there maybe once a month, and was accessible and wanted to talk to all us young tech start-up people."

Currently building his fifth business - a digital human resources tool - from Are's snowy mountains, Mr Formgren has already raised "close to half a million dollars" in investment for his latest venture.

Yet it's worth noting that these are details he only discloses after 30 minutes of conversation. And it is this aspect of Jantelagen - avoiding bragging - that many argue is detrimental to Sweden's tech scene.

"It has made it more difficult to have role models," argues Ulrika Wiklund.

"The people that succeed, they don't dare to drive a luxury car, they don't dare to show when they have done something good. Maybe that has made it more difficult to inspire entrepreneurs."

Stockholm business school head Sofia Wingren encourages entrepreneurs to talk more about their success

Swedish start-ups attracted €1.3bn ($1.6bn: £1.1bn) in 2017, according to figures from European venture capital database Dealroom.co, external - compared to €2.9bn in Germany and €7.1bn in the UK.

While the statistics are impressive given Sweden's size, does Jantelagen hold back companies from aiming higher?

"Research suggests you receive capital depending how confident and boastful you are about your idea," says Sofia Wingren, chief executive of Hyper Island, a business school in Stockholm with a focus on equipping students for careers in the digital sector.

She argues that Swedes have typically been too susceptible to "working in the quiet" to "perfect" products, before seeking funding or launching them on to the market.

More Technology of Business

While Hyper Island's current crop of millennial students is less bashful and more globally-minded than previous generations, a core part of the school's teaching is focussed on trying to address this issue.

"We have a lot of performances or stage presentations where we coach and guide students on how... to present themselves and how to be confident," Ms Wingren says.

External factors will clearly also play a role in Sweden maintaining its reputation as a leading innovation hub.

Students at the Hyper Island business school

An acute housing crisis, taxes on stock options and strict migration regulations are fuelling national debates about the country's ability to attract the global skills needed to help companies in the small Nordic nation to realise their ideas.

Meanwhile, observers point to the challenge of maintaining the emphasis on trust and consensus that characterises Swedish business practices, in the face of growing global competition from other innovation hubs and rapid digitalisation.

"The world is moving so fast that we may not have time to get everybody's opinion," argues Lola Akinmade Akerstrom.

"Sweden has to find the sweet spot. It's about taking the best parts of that consensus mindset and a culture steeped in organisation, and being open to creativity and flexibility and diverse points of views and ways of working."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external