Lessons delivered by taxi, truck and boat

- Published

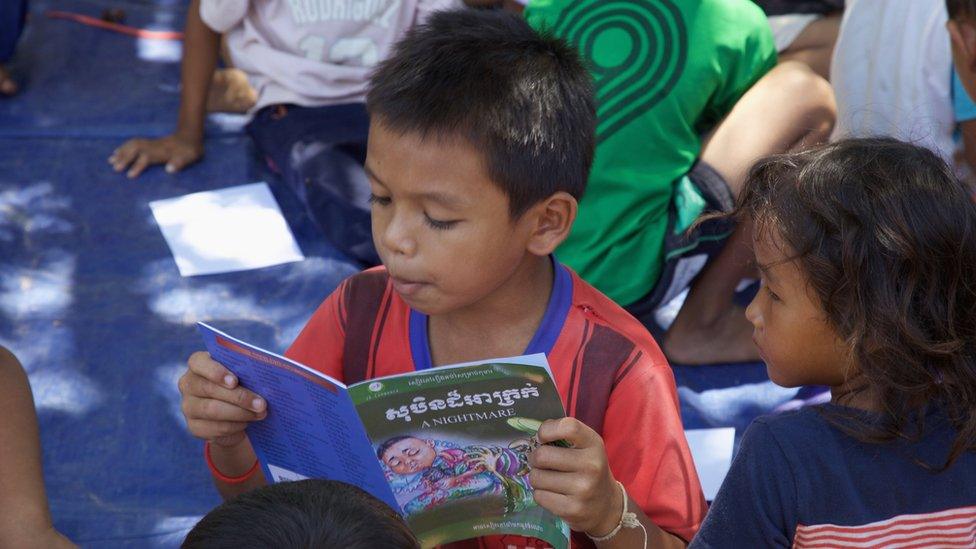

In Cambodia, lessons are brought to remote villages by the Book Book Tuk Tuk

If children can't get to lessons, a project in rural Cambodia is showing how lessons can be brought to them.

Tuk- tuks, the motorised rickshaws used across south-east Asia, are delivering textbooks and lessons to remote villages in a scheme known as "Book Book Tuk-Tuk".

It can be difficult and expensive for students to get an education in rural Cambodia and a school in Takhmau, south of Phnom Penh is experimenting with taking lessons directly to them.

Kuma Cambodia, a school founded in 2012 by the Norwegian Association for Private Initiative in Cambodia (NAPIC), decided to dispatch libraries on wheels to remote areas, to bring books to rural children.

The Book Book Tuk Tuk project, working with village chiefs to encourage participation, sends out tuk-tuks staffed by Cambodian volunteers, many of whom are just out of school themselves.

They educate families about why it's important to send children to school, as well as addressing social issues such as HIV awareness and concerns about gambling.

'Cycle of poverty'

Volunteer Pring Mean, a 21-year-old Cambodian, explained: "Not letting children go to school is common among the poorest.

"Parents do not understand the value of education, family income is too low and so children need to work or look after young siblings, or parents suffer from drugs or alcohol addiction," says Mean.

Children get a chance to see books from the mobile library and to get help from volunteer staff

"When children aren't sent to school they're more vulnerable to exploitation and getting involved in drugs or crime. Without access to education they remain in the cycle of poverty."

The tuk-tuk volunteers teach children maths, how to draw, read, sing, and tell them traditional Cambodian stories.

Although the libraries provide access to literature and advice, their primary function is to encourage parents to send their children to school.

Seavsean, a 10-year-old Cambodian girl, lived under a plastic sheet with her parents and brother in a rural village in Kandal province.

Her father gambled away the family's earnings, leaving her mother to sneak out at night to steal rice to feed her children.

Bringing books to rural villages helps communities which can miss out on schools

But after participating in the parent programme at Book Book Tuk Tuk, Seavsean's father stopped drinking and got a job. Now, they live in a brick house, and Seavsean attends school at Kuma Cambodia.

"We believe giving parents more knowledge, hope and motivation to help them change their destructive behaviour - like gambling, drug abuse or domestic violence - and break the cycle for their children," said Pring Mean.

But Book Book Tuk Tuk isn't the only classroom taking to the road to reach children.

Teaching English by video

Teachers from the US deliver live English lessons on video to learners in Indonesia

In Indonesia, a lack of qualified English language teachers means many students' future employment prospects are limited. Children in low-income, rural areas have little or no access to English language teaching, while unreliable, expensive internet access rules out online learning.

So three organisations, Oxford University Press (OUP), car group IndoMobil and US teaching network Eleutian, combined forces to kit out trucks with satellite technology, linking Indonesian students with US-based teachers.

The trucks are driven to low-income communities across the country, park somewhere open - such as a playground - and set up.

The side of the truck folds away to reveal a large TV screen, with shade from the sun and rain, and students learn from OUP's syllabus from a teacher leading the class in real time from the US.

"English proficiency is becoming increasingly important in developing countries, says OUP's Joseph Noble. "This is particularly true in Indonesia. However, many students are being left behind."

Since its inception, the TeachCast project has reached more than a thousand students, and has plans to expand its current fleet of 15 trucks to 500, with each truck teaching 150 students per day.

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk

Floating schools

In Bangladesh, much of the country is prone to flooding, classrooms on wheels aren't always a viable option. Flooding severely impacts children's education, adding to the country's four million children who are already out of school.

"Schools struggle against floods and riverbank erosion," says Mohammed Rezwan, executive director of non-profit organisation Shidhulai Swanirvar Sangstha. "The river is known as the 'destroyer of establishments'.

In Bangladesh, thousands of children learn on floating classrooms

"Schooling opportunities are already very limited for the extremely poor, and when roads become impassable during the monsoon, students can't trek to school.

"School dropouts are common in these rural regions," he says.

Rezwan's family owned a small boat, meaning he could attend school during monsoon season, and Rezwan was inspired to create "floating schools".

"I thought if children couldn't come to school, then the school should come to them."

The floating schools collect children from stops along the river

The organisation now owns 22 school boats, and educates nearly 2,000 children, who are collected from various riverside villages throughout the day.

After the boat docks at its final destination, class begins. Each boat is equipped with solar powered electricity, a laptop, and a classroom for 30 students.

Seven-year-old Suraiya Khatun, from Pabna likes this form of mobile learning.

"When I'm older I want to be a floating school teacher to teach children in our village," she says.