Have you ever dreamed of flying in your car?

- Published

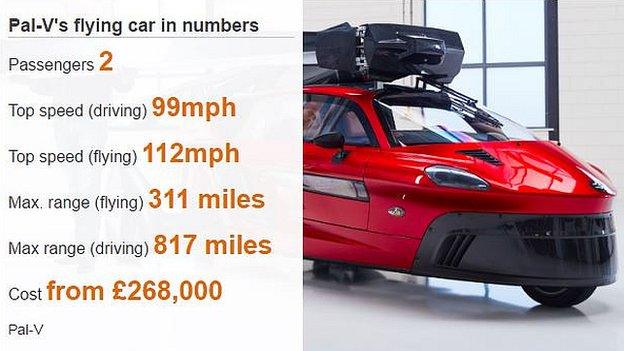

The flying car that costs nearly £300,000

As Dutch company Pal-V unveils its latest flying car gyrocopter at the Geneva motor show, we ask if the dream of flying cars for all could ever become a reality.

"007 was here" says the graffiti emblazoned on the wall of Pal-V's stand at the Geneva motor show. Beneath it sits a creation James Bond would certainly be proud of.

The Dutch company has just launched its first flying car on to the market.

It's a compact three-wheeler, which it says can offer sporty performance on the road then take to the air using a set of extendable rotors.

So is this a sign that air travel is about to get a whole lot more accessible, or will devices like this never be more than playthings for the rich?

The car is called the Liberty. In flying terms, it is what's known as an auto-gyro, or gyrocopter.

In other words, it has helicopter-like blades that rotate freely in order to generate lift, while power is provided by two 100 horsepower engines, via a separate propeller at the back.

James Bond, aka 007, flew something similar in the film You Only Live Twice - a nippy runaround called Little Nellie - and the company is clearly quite happy with the comparison.

But the Liberty is bigger, more luxurious, and it can also be used on the road, which means it is no ordinary autogyro.

It can use one of its two engines to drive at up to 99mph (160km/h) on the ground, enabling the pilot to drive straight from the runway to his or her destination.

The secret to doing this effectively, the company says, is technology that allows the car to tilt into corners and remain stable, despite its three-wheel design.

Little Nellie, the gyrocopter flown by James Bond in You Only Live Twice

It is this practicality that Pal-V thinks will be Liberty's main selling point.

"It's the frustration of general aviation," says chief executive Robert Dingemanse

"With a small plane or a helicopter you take off from a place you don't want to leave from, and end up in a place you don't really want to be.

"But if you drive, you can start at your garage door, then go straight to the place you want to be - and that's what we offer - 3D mobility."

But a gyrocopter design has its drawbacks, argues Prof Harry Hoster, head of Lancaster University's Energy Research Centre.

"Gyrocopters can land in a very small area, unlike normal helicopters," he says, "but they still need a bit of forward momentum before they can take off, so they wouldn't be able to use helicopter pads on the top of buildings, for example.

"And you would have issues in densely populated areas," he adds, "because the rotors would need a large radius of free space."

Noise would also be an issue in urban areas, Prof Hoster believes.

Ready for take-off? Terrafugia's 'Transition' flying car

Pal-V isn't the only company trying to make a commercial success out of a flying car. Others have taken a different approach, opting for fixed or folding wing designs.

US-based Terrafugia, for example, which was recently bought by Volvo's Chinese owner Geely, has developed a flying car whose hinged wings fold up neatly after flight.

Chris Jaran, Terrafugia's chief executive, tells the BBC: "You can fit it in your garage, you can drive it to any airport, you can unfold the wings, fly it to another airport, fold it up and drive to your destination."

The petrol-powered vehicle, which can travel at 70mph [113km/h] on the road and 100mph in the air, meets "all of the regulations for airplanes and cars in the United States", says Mr Jaran.

Co-founders Anna and Carl Dietrich hope their craft will bring the vision of personal aviation for the masses a little closer. But at around $280,000 (£202,000) that's hardly a mass-market price.

And the need to drive to an airport to fly the thing is another major drawback - one the company acknowledges.

So it is working on a new version, the TF-X, featuring propellers that can tilt upwards for vertical lift-off, then tilt downwards for forward propulsion.

This car can turn into an aeroplane in just three minutes

Then there's Slovak firm AeroMobil - it has developed a car with wings that swing back tidily behind the cockpit after flight. It uses electric power on the road and a gasoline engine in the air. Yours for a mere $1.2m (£860,000).

Nick Wirth, technical director at Wirth Research, a specialist racing car and drone designer, thinks that regulation is the flying car's biggest obstacle, not technology.

"Regulations covering airworthiness have been developed over 100 years, so it takes years of work to get something cleared for use by pilots. Crashing in an aircraft is usually a lot more serious than crashing in a car," says Mr Wirth, a fellow of the Royal Academy of Engineering.

"It's a huge difference owning and operating a car to owning and operating an aircraft."

Current regulatory regimes around the world require flying car owners to have a pilot's licence, another potential barrier to mass adoption.

More Technology of Business

"The problem is that you end up with a product that needs so much engineering and regulation around it you end up with something that's incredibly expensive," says Mr Wirth.

"Is there a market for this? There might be, but it's going to be tiny."

And Bill Read, deputy editor of Aerospace, the Royal Aeronautical Society's magazine, says: "If you have lots of them you'll have the equivalent of aerial traffic jams, so you'd have to have air corridors, specific heights they must fly at, and other rules for flying over cities.

"I think autonomous sky taxis stand more of a chance of achieving regulatory approval than flying cars."

Mr Dingemanse says the Pal-V Liberty has been designed from the ground up to comply with aviation and road safety regulations. But like its potential rivals, it doesn't come cheap.

An initial limited edition model will cost €500,000 (£450,000) - while the standard version will still set you back €300,000 (£270,000). The company hopes to sell about 1,000 aircraft a year.

But so far, it hasn't sold any to spies.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external