Baselworld: Watch industry's glamour show opens amid sales recovery

- Published

Last year's Baselworld attracted 135,000 visitors and 4,400 journalists

We may live in increasingly digital times, but there is still a part of the globe where analogue rules. Welcome to Baselworld, the biggest watch and jewellery show on the planet.

For the next six days, almost 800 exhibitors will be displaying their latest wares in the Swiss city of Basel.

But we're not talking about the standard watches available in your local department store. It's a world where even entry-level products can cost several thousand pounds, rising to hundreds of thousands.

These are precision-made, often one-off or limited-edition pieces that may take years to engineer. A basic mechanical wrist watch might have, perhaps, 100 parts. Patek Philippe's Calibre 89 pocket watch has 1,728.

And to underline the distinctiveness, the big brands will be bringing along a roster of celebrities, actors and sports men and women to sprinkle stardust over their latest products.

Maradona, Usain Bolt, and Jose Mourinho are among famous sporting names scheduled to attend - and that's just as guests of Hublot, the Swiss luxury brand and part of France's LVMH group.

Is it all worth it? "Baselworld remains by far the most important gathering for the watch industry," says Hublot's chief executive Ricardo Guadalupe. "It is great to present a stunning timepiece. We go where our clients are."

One of the company's showpiece unveilings will be what it says is the world's first watch made of brightly coloured ceramic - something the R&D team took four years to develop, he says.

Hublot spent four years on the now-patented process for its highly-polished ceramic Red Magic watch. Only 500 will be made

New products are usually kept under wraps until the launch date. But it's a fair bet that unveilings from Rolex, which first exhibited in Basel in 1939, will again be among the show's biggest attractions for the visiting retailers, collectors and enthusiasts.

There will also be several new hybrid smartwatches - traditional-looking timepieces offering connectivity. Watchmakers like to trade on their heritage, but many are all too aware of the future threat from Apple and other smartwatch makers.

For a piece of true Swiss watchmaking tradition, visitors go to Patek Philippe. Queen Victoria and Prince Albert both bought Patek timepieces at London's Great Exhibition in 1851.

The company keeps alive the traditions of enamelling and marquetry, and its Rare Handcrafts collection is always a big draw.

Like fast-car engineers, high-end watchmakers see themselves as producers of hi-tech machines - only in miniature. And like fashion designers, some of the works seem more designed to wow rather than sell.

Geneva-based Maximilian Busser and Friends (MB&F) has a history of unveiling unusual and avant-garde work.

"There's no real rational reason [to make them] except that they are wonderful pieces of art," says the firm's Charris Yadigaroglou. "The reason is the beauty and the mechanics."

MB&F worked with specialist designer L'Epée 1839 for this combined clock, barometer, thermometer, hygrometer - called The Fifth Element

However, the glitz and glamour of Baselworld can't hide that the watchmaking industry has been through a rough patch. Although, after two years of recession, there are definite signs of improvement.

The length of this year's show - now in its 101st year - has been cut from eight to six days, and the number of exhibitors is down by about 400.

There are grumblings about the cost of exhibiting, reportedly more than $5m (£3.5m) for a half-decent position in the arena, and several manufacturers have decided to hold their events off-site in nearby hotels and buildings.

There's also rivalry between watch shows. Switzerland is famously the centre of the watchmaking universe - there are about 700 firms involved in the industry - and Baselworld is not the country's only trade event.

And money is still tight. The global economic slowdown, coupled with China's crackdown on corruption (expensive watches make good gifts) and the popularity of smart devices among younger consumers, has made manufactures cautious.

There is, though, light at the end of the tunnel.

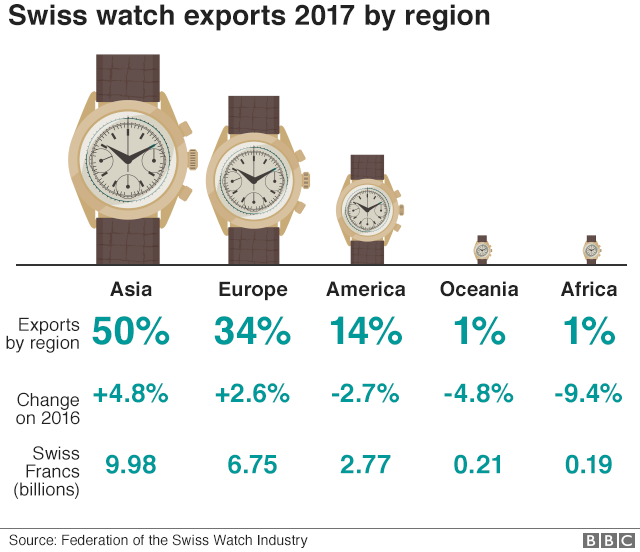

The value of Swiss watch exports rose by 2.7% to 20bn francs (£16bn) in 2017 from 2016, according to the Federation of the Swiss Watch Industry. Add the mark-up from retailers and distributors, and the total value of Swiss pieces is probably three of four times that, says the Federation's president Jean-Daniel Pasche.

Although the total number of wrist watches shipped fell 4.3% to just over 24.3 million units last year, it underlined a shift the industry has seen recently - sales of more expensive items are doing well, while sales of watches retailing for less than 200 francs are falling.

That's good for the Swiss industry. Mr Pasche said that while Switzerland accounts for just 2% to 3% of watches made - China is the biggest producer - the Swiss made label accounts for 50% of the market by value.

"The average price for a Chinese watch is about $4. For Swiss-made it's $800 (£570). The Japanese are somewhere in between on price," says Mr Pasche.

Switzerland's export growth has continued into 2018, with shipments up 12.6% in January and 12.9% in February compared with the same months last year, the Federation announced this week, external.

The rebound has been driven by a resurgence in exports to Asia, and particularly China and Hong Kong. Even exports to the US, which has lagged recovery elsewhere, rose 26% in February.

The industry's improvement was underlined by Swatch Group, the world's largest manufacturer whose brands include Omega, Tissot, Breguet, and Longines, which reported a return to profit for 2016.

However, no one is forecasting a return to the boom times just yet.

The sales crunch of recent years was nothing like the so-called Quartz Crisis of the 1970s and early '80s, when Japan's new battery-powered watches caused upheaval in Switzerland and led to 60,000 job losses.

But now that sales of low-end watches are falling, Japan is once again a threat. As Seiko Watch President Shuji Takahashi told Bloomberg earlier this month:, external "It's only natural we start to shift more towards mid- and high-end."

And the rise and rise of the smartwatch remains a constant threat. Indeed, Apple is now the single biggest watchmaker.

Could the Swiss industry's recovery be short-lived? "We don't fear competition," is Mr Pasche's bullish answer. "It's up to our brands to keep their leadership position."