The Swedes rebelling against a cashless society

- Published

Majlis Jonsson, 73, says she prefers using cash

Sweden is winning the race towards becoming the world's first completely cashless society, but there are growing concerns it's causing problems for the elderly and other vulnerable groups.

None of the High Street banks around Stockholm's spotless Odenplan square handle cash any more.

You can only pay for your coffee and cinnamon bun by card or with your smartphone at the local branch of the country's largest cafe chain. And there's no chance of using coins or notes if you want to hop on one of the shiny blue busses whizzing past.

Yet for Swedes there's nothing unusual about how cashless this inner city neighbourhood has become in recent years.

The vast majority of the nation's banks have long stopped allowing customers to withdraw or pay in cash over-the-counter.

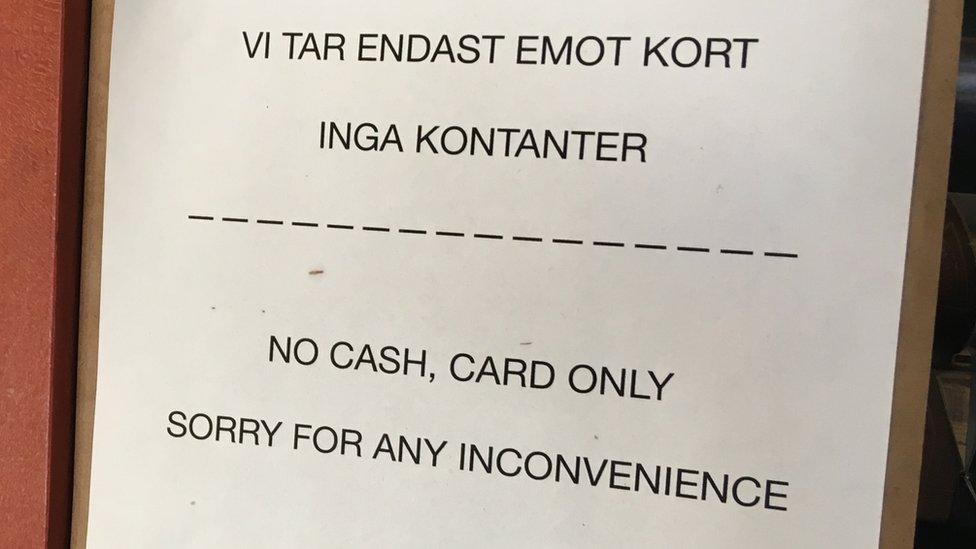

Many Swedish shops and restaurants now only accept card or mobile payment systems

Only a quarter of people living in Sweden say they use cash at least once a week and a boom in mobile, card and online payments has resulted in the proportion of cash transactions in the retail sector dropping from around 40% in 2010 to 15% today, according to the central bank.

However, while Sweden's rush to embrace digital payments has received plenty of global hype, and is frequently flagged as an example of the Nordic nation's innovation, there are growing concerns about the pace of change.

Some worry about the challenges it poses for vulnerable groups, especially the elderly.

"As long as there is the right to use cash in Sweden, we think people should have the option to use it and be able to put money in the bank," says Ola Nilsson, a spokesperson for the Swedish National Pensioners' Organisation, which is lobbying the government on behalf of its 350,000 members.

"We're not against the cashless society, we just want to stop it from going too fast."

There has been a nationwide boom in mobile, card and online payments

Majlis Jonsson, 73, who's lived in Odenplan for more than 20 years, is out running errands in the spring sunshine. She says she still likes to "pay with cash as often as possible" and fears a future where that's no longer possible.

"Sometimes in places I don't know, I don't feel secure to use my card," argues the former teacher.

Since she doesn't have a computer at home and is nervous about using the internet, the cashless trend is also making life more expensive for her. Most Swedish banks stopped accepting cheques years ago and have pushed up fees for in-branch bank transfers.

It recently cost Ms Jonsson 75 kronor (£6.35) to pay back a friend who booked a train ticket for her online.

"It's a lot of money. The banks - they are so rich! Of course they always say you can do it for free on the internet, but it's a problem - there are still some that don't know how to do it."

Viktor Sjoberg, a customer advisor at SEB, says the bank wants to offer a blend of the digital and physical worlds

Eurostat figures suggest she is part of a shrinking minority, with 85% of Swedish 16 to 74-year-olds banking online in 2017. That is compared to an EU average of 51% and 68% in the UK.

But the Swedish National Pensioners' Organisation argues that Swedes who can't or won't accept the cashless trend can end up feeling even more excluded than they might elsewhere.

"It shouldn't be more expensive if you can't use digital devices," says Mr Nilsson, who believes banks have been too focussed on cutting costs.

"We want to see more digital training for elderly people. That could come from the banks themselves or from more funding from the state to help us support our members and other older people."

SEB, one of Sweden's largest banks, has already started offering what it describes as "learning support" in many of its locations, but the move comes as the bank is shifting its model even further away from traditional over-the-counter services.

Cash is only handled in seven of SEB's 118 branches

Cash is only handled in seven out of a total of 118 branches and the bank recently announced a new focus on providing digital tools in branches, designed to encourage visitors to complete banking tasks themselves, with staff on hand to answer questions if they get stuck.

"We believe in a blend between the digital world and the physical world," says Viktor Sjoberg, a customer advisor at SEB's flagship branch in central Stockholm. He is convinced that bringing back more cash-based services would "go against customer demand".

"There's no need to keep an infrastructure alive if no-one uses it," he says.

Sweden's central bank, the Riksbank, has adopted a more cautious tone. In its annual report in February, external, it said that while transformation of the nation's payments infrastructure was "essentially positive", it needed to take place "at a rate that does not create problems for certain social groups or exclude anyone from the payment market".

Meanwhile the bank's governor Stefan Ingves has argued that phasing out coins and notes could put the entire country at risk should Sweden encounter a "serious crisis or war".

Against this background a Swedish parliamentary commission has begun a major review of these and other potential consequences of a cash-free economy, with a report expected later this year.

Dr Bogusz believes pensioners will catch up with the cashless trend

"There is definitely a sense that becoming cashless is inevitable, so it's mostly a case of mitigating any implications," says Dr Claire Ingram Bogusz, a postdoctoral researcher at Stockholm School of Economics, who is studying Sweden's increased use of digital payment platforms.

"In the context of these debates, I think pensioners will catch up... Both the Riksbank and the government are very interested in supporting vulnerable groups."

However, she says that while Swedes' high level of trust in both institutions and new technologies has played a big role in people embracing a more cash-free economy, concerns about fraud and data protection are now influencing the debate.

"Swedes are very trusting but I think that is changing. For example the recent Cambridge Analytica scandal has made people more aware of how their data is being used," Dr Bogusz says.

Kafe Orion has banned cash payments

Despite the nationwide plunge in the use of coins and notes, a survey by Swedish polling firm Sifo earlier this month suggested that seven out of 10 Swedes still want the option be able to pay with cash in future.

The results reflect the divided opinions of customers at Kafe Orion in Odenplan, an independent cafe that has joined numerous Swedish restaurants and stores in banning all cash payments.

"I don't see that it's good if we are going to be entirely cashless because I think there should be an option to use cash - for example if the internet goes down," says 23-year-old student Agata Oleksiak.

But her friend Johan Johnson, 24, strongly disagrees: "You can use your card online and in coffee shops and I just don't see a use for hard cash any more. Of course your card could get stolen, but your insurance will pay for it.

"I think that cash is out of date and not really necessary."

- Published14 March 2018

- Published12 October 2017

- Published12 September 2017