JK Rowling wants happy ending for orphans

- Published

JK Rowling's charity says many children in orphanages are not orphans and should be with their family

A mission to take children out of poorly-run orphanages could be something from a Harry Potter plot.

But that is the goal of a charity founded by JK Rowling.

The charity, Lumos, works with governments in countries like Moldova and Ukraine to reform their education and child protection systems.

But it is a tale of steady bureaucratic reform rather than daring adventure.

Lumos, which the Potter author founded after reading an article about children being kept in caged beds in an orphanage, is on a mission to end the placing of children in poor-quality institutions by 2050.

Potter fans will notice that the charity is named after the spell used by witches and wizards to bring light to dark places.

And Lumos wants to challenge some perceptions.

Poor quality care

It wants people in Europe and the US to think twice about sponsoring or supporting orphanages in other countries, unless they can be sure of what is being provided.

It wants to make a distinction between "high-quality residential care" and institutions where children are "arbitrarily separated from their parents" and where they might be isolated from other schoolchildren and the wider community.

Lumos chief executive Georgette Mulheir wants to warn people about the conditions in which children can be kept

The charity warns that in some orphanages many of the children will not be orphans, but separated from their families because of poverty and discrimination.

There are concerns about children being exposed to risks of abuse and trafficking - and there are warnings that children can have worse education and life outcomes than if they attended inclusive schools in their communities.

"A lot of people do not know there are millions of children in these institutions, and most of these children have parents who want them," says Lumos chief executive Georgette Mulheir.

"Most people think they are orphans who need looking after, they do not know the serious harm that institutionalisation does to children's development."

Inclusive classes

At least eight million children live in orphanages and residential institutions, yet more than 80% are not actually orphans, says the charity.

One of Lumos's first successes was to help to take children out of institutions in Moldova by reforming the country's education system to make it more inclusive.

The author visited children in Moldova where Lumos has been working

It is currently working in Ukraine, which has more than 100,000 children in institutions, to develop an inclusive education system and reform the child protection system.

This involves training teachers, adapting the curriculum, and changing existing rules which hold back some children - for example, adapting exams so that children with learning difficulties can progress to the next school year.

In another comparison to Potter, the advocacy of children has been an important part of the campaign.

Warning to donors

Before Moldova's government agreed to reform its education system, a boy from a mainstream school made an impassioned speech to the country's education minister.

"It was great to watch this young man wagging his finger at the minister, saying 'we mean it, we expect you to do this'," says Ms Mulheir. "It had quite an impact on her."

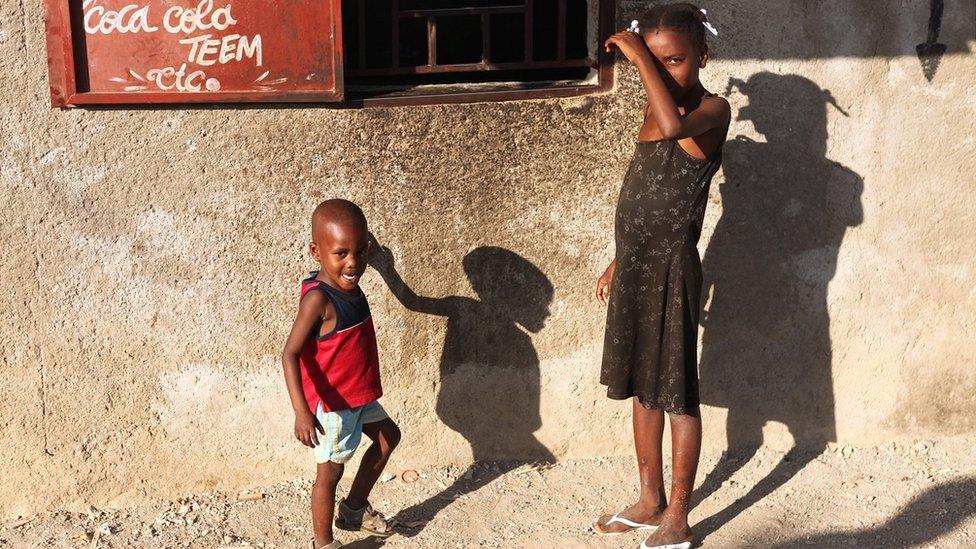

The charity has been working to help children in Haiti

Ms Mulheir says the problem of children in inappropriate institutions is not confined to less developed countries - these places still exist in some of the richest countries in the world.

"People would be quite shocked to learn about the situation in Belgium and to a lesser extent France, where there are still institutions for babies even though all of the evidence shows this seriously harms early brain development," she says.

Last year, a report by Lumos warned that charitable givers from the US who believed they are helping orphans in Haiti could be funding places where children were at risk of abuse.

More than a third of Haiti's orphanages are funded by donations from abroad.

"One of the things that Lumos has taught me is be very, very careful how you give," JK Rowling said after the report's launch.

She said "very, very well-meaning donors" are "inadvertently propping up a system that we know, with nearly 80 years of hard research, shows that even a well-run institution, even an institution set up with the best possible intentions, will irrevocably harm the child".

Lumos is now expanding its work into new countries, including Colombia.

"We are really confident that by 2050 at the latest there will be no more children in institutions anywhere in the world," says Ms Mulheir.

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk