The veggie burger that bleeds when you cut it

- Published

It looks like meat, it even bleeds. But does it taste meaty enough to convert committed carnivores?

The meat industry is a major contributor to carbon dioxide emissions and deforestation, and a huge consumer of water. But can lab-grown veggie alternatives wean us off our addiction to red meat? Silicon Valley tech companies are betting on it.

Evan McCormack, 19, is staring at a big juicy burger on his plate at a local cafe. It looks like meat. It smells like meat. It even bleeds like meat. But it's not.

"I like how juicy and crunchy it is, compared to a lot of other veggie burgers," he says. "I think the texture is a big part of it."

Made from ingredients such as wheat, coconut oil and potatoes by Impossible Foods in Silicon Valley, this burger might even fool his meat-loving friends at college, he believes.

The firm's chief executive Pat Brown has ambitious plans to replace animals completely as "a food production technology" by 2035.

Evan McCormack liked "how juicy and crunchy" his Impossible Burger was

His main motivation? The environment.

He views farmed animals like little factories, and seethes about the existing meat, fish and dairy industries.

"That technology is the most destructive technology on earth - more than fossil fuel production, the transportation system, mining and logging," he claims.

"It's a major source of greenhouse gases, and the biggest user and polluter of water."

He has a point. Livestock production is responsible for 18% of total greenhouse gases, according to the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO). And animal protein requires 11 times the amount of fossil fuel to produce compared to plant protein, says the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International.

Huge swathes of Amazonian forest have been cleared for cattle rearing in Brazil

Ancient forests in the Amazon and elsewhere are being decimated to make way for pasture land and feed crops.

But the industry also employs more than a billion people and provides a third of the world's protein, the FAO says. Meat production was 229m tonnes at the turn of the Millennium, but is forecast to double to 465m tonnes by 2050.

So Mr Brown has his work cut out for him.

The Impossible Burger may be proving popular with the environmentalists and vegetarians of Silicon Valley, but for now it's only available in select restaurants across the US.

The company produces about 500,000 pounds of burgers a month at its Oakland factory and plans to ramp up production for supermarkets by 2020. It's also working on fish products.

Machines at Impossible Foods creating the plant protein heme, a key ingredient

Mr Brown's team of biochemists has found a way to mass-produce heme - a plant-based iron-containing molecule that resembles blood. It's literally the "secret sauce" that gives the burger its competitive advantage.

The team has adapted existing technologies, such as gas chromatography-mass spectrometry and texture probes, to analyse the smell, taste and texture of meat. It then replicates it in the lab using plant-based proteins.

Impossible claims tests among meat lovers have shown their burger to be indistinguishable from meat 47% of the time. They're striving to break the 50% barrier.

"We have to produce products that do a better job of pleasing consumers than the current technology does or we fail," says Mr Brown.

Scaling up is a big challenge, so the company is eagerly looking for partners.

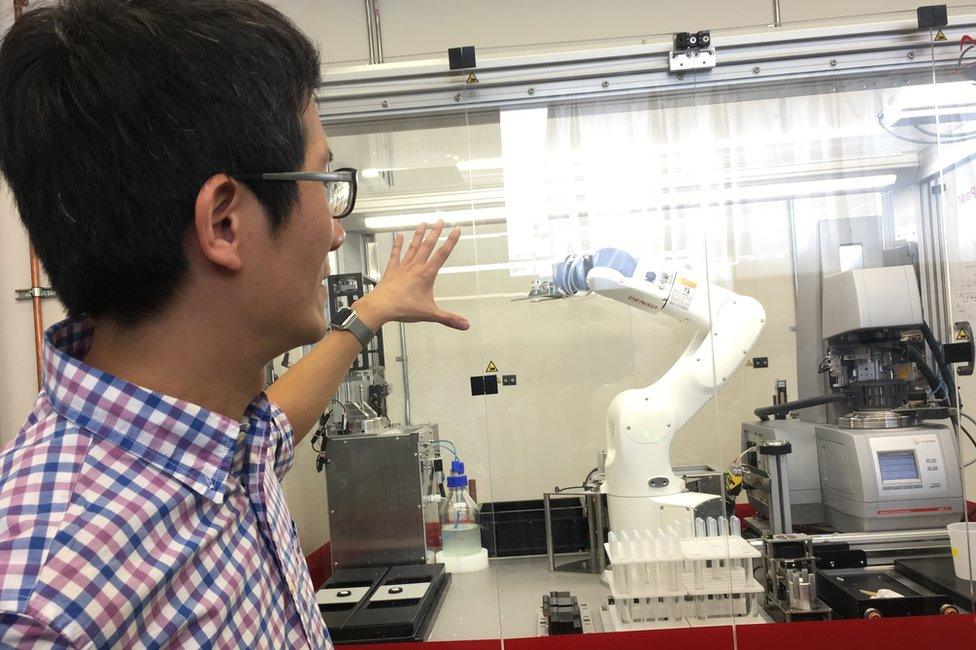

Chingyao Yang shows off one of Just Inc's robots that help speed up food development

Another way of producing meat is literally to grow it in the lab from animal cells. This "in vitro" or "clean meat" approach is being pursued by two Silicon Valley companies - Memphis Meats and Just Inc.

At the Just lab, automation engineer Chingyao Yang introduces me to the robots that speed up analysis of molecular interaction. Essentially, they're fast-tracking molecular recipes.

"We're using data and algorithms to increase the probability of discoveries," says Mr Yang.

Then senior scientist Vitor Espirito Santo shows off shelves of fridge-like containers agitating flasks filled with cells marinating in experimental "growth cocktails."

An artist rendering shows a Brave New World vision of tall vats and slabs of steak on conveyor belts.

"This is our farm for the clean meat production," says Mr Espirito Santo. "The scale matches the biggest slaughterhouse in the US, but instead of cows it has 200,000 litre [50,000 gallon] bioreactors.

More Technology of Business

"Bioprinting will make products like steaks, chicken... everything you can imagine in terms of meat."

He says the company will release its first ground meat later in 2018, with higher complexity products coming over the next few years.

"Kobe beef and chicken breast is at the end of the road ...we'll get there," he says.

Across the San Francisco Bay, Memphis Meats is famous for its $18,000 "clean" meatball. Chief executive Uma Valeti tells me his mantra is: "Better meat, less heat!"

Memphis Meats develops meat products grown from animal cells

By growing meat in the lab, he hopes to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from meat production by up to 90%.

With funding from Bill Gates and Richard Branson, as well as traditional meat suppliers Cargill and Tyson Foods, Memphis Meats has some serious money behind it.

And the meat substitute market generally is forecast to grow 8.4% a year from 2015, says Allied Market Research, reaching a value of $5.2bn by 2020.

But can these tech start-ups really take on the formidable might of the global meat industry?

Back at the cafe, Evan McCormack's father Richard, who's been vegetarian for decades, is less enthusiastic about the Impossible Burger than his son. He thinks it's indistinguishable from other veggie patties.

"It's three dollars more than the standard burger!" he complains. "Why? Because it has a little red flag in it?"

Click here for more Technology of Business features, external

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external