'More than 600 apps had access to my iPhone data'

- Published

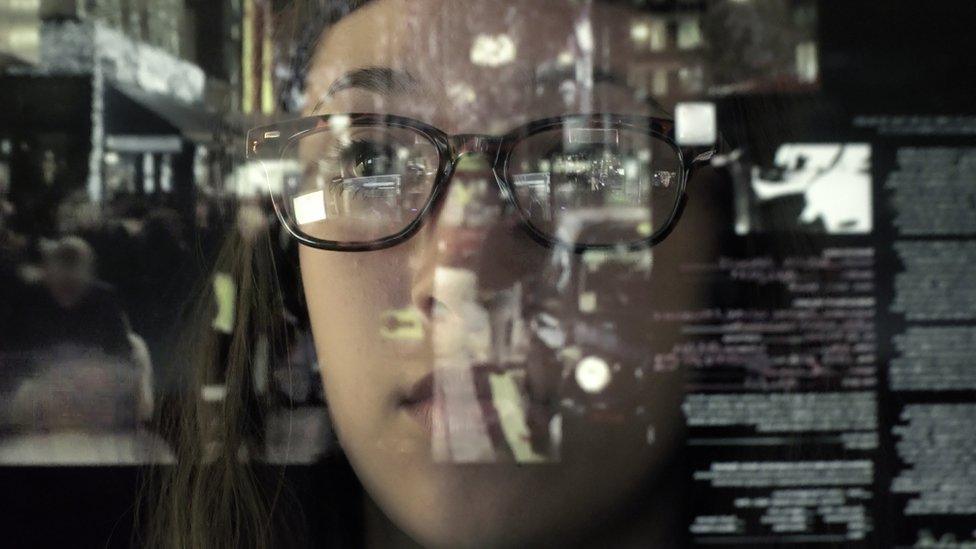

Frederike Kaltheuner thinks we may never be able to find out how much firms know about us

While Facebook desperately tightens controls over how third parties access its users' data - trying to mend its damaged reputation - attention is focusing on the wider issue of data harvesting and the threat it poses to our personal privacy.

Data harvesting is a multibillion dollar industry and the sobering truth is that you may never know just how much data companies hold about you, or how to delete it.

That's the startling conclusion drawn by some privacy campaigners and technology companies.

"Thousands of companies are in the business of harvesting your data and tracking your online behaviour," says Frederike Kaltheuner, data programme lead for lobby group Privacy International.

"It's a global business. And not just online, but offline, too, via loyalty cards and wi-fi tracking of your mobile. It's almost impossible to know what's happening to your data."

The really big data brokers - firms such as Acxiom, Experian, Quantium, Corelogic, eBureau, ID Analytics - can hold as many as 3,000 data points on every consumer, says the US Federal Trade Commission.

Do you know how many apps you've shared your personal data with?

Ms Kaltheuner says more than 600 apps have had access to her iPhone data over the last six years. So she's taken on the onerous task of finding out exactly what these apps know about her.

"It could take a year," she says, because it involves poring over every privacy policy then contacting the app provider to ask them. And not taking "no" for an answer.

Not only is it difficult to know what data is out there, it is also difficult to know how accurate it is.

"They got my income totally wrong, they got my marital status wrong," says Pamela Dixon, executive director of the World Privacy Forum, another privacy rights lobby group.

She was examining her record with one of the merchants that scoop up and sell data on individuals around the globe.

She found herself listed as a computer enthusiast - "which is a bit annoying, I'm not running around buying computers every day" - and as a runner, though she's a cyclist.

Privacy campaigner Pamela Dixon found that marketing data about her was inaccurate

Susan Bidel, senior analyst at Forrester Research in New York, who covers data brokers, says a common belief in the industry is that only "50% of this data is accurate".

So why does any of this matter?

Because this "ridiculous marketing data", as Ms Dixon calls it, is now determining life chances.

Consumer data - our likes, dislikes, buying behaviour, income level, leisure pursuits, personalities and so on - certainly helps brands target their advertising dollars more effectively.

But its main use "is to reduce risk of one kind or another, not to target ads," believes John Deighton, a professor at Harvard Business School who writes on the industry.

We're all given credit scores these days.

If the information flatters you, your credit cards and mortgages will be much cheaper, and you will pass employment background checks more easily, says Prof Deighton.

How the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal unfolded

But these scores may not only be inaccurate, they may be discriminatory, hiding information about race, marital status, and religion, says Ms Dixon.

"An individual may never realize that he or she did not receive an interview, job, discount, premium, coupon, or opportunity due to a low score," the World Privacy Forum concludes in a report.

Collecting consumer data has been going on for as long as companies have been trying to sell us stuff.

As far back as 1841, Dun & Bradstreet collected credit information and gossip on possible credit-seekers. In the 1970s, list brokers offered magnetic tapes containing data on a bewildering array of groups: holders of fishing licences, magazine subscribers, or people likely to inherit wealth.

But nowadays, the sheer scale of online data has swamped the traditional offline census and voter registration data.

Cambridge Analytica claims its research gave President Trump his winning edge

Much of this data is aggregated and anonymised, but much of it isn't. And many of us have little or no idea how much data we're sharing, often because we agree to online terms and conditions without reading them. Perhaps understandably.

Two researchers at Carnegie Mellon University in the US worked out that if you were to read every privacy policy you came across online, it would take you 76 days, reading eight hours a day.

And anyway, having to do this "shouldn't be a citizen's job", argues Frederike Kaltheuner, "Companies should have to protect our data as a default."

Rashmi Knowles from security firm RSA points out that it's not just data harvesters and advertisers who are in the market for our data.

"Often hackers can answer your security question answers - things like date of birth, mother's maiden name, and so on - because you have shared this information in the public domain," she says.

"You would be amazed how easy it is to piece together a fairly accurate profile from just a few snippets of information, and this information can be used for identity theft."

So how can we take control of our data?

There are ways we can restrict the amount of data we share with third parties - changing browser settings to block cookies, for example, using ad-blocking software, browsing "incognito" or using virtual private networks.

More Technology of Business

And search engines like DuckDuckGo limit the amount of information they reveal to online tracking systems.

But StJohn Deakins, founder and chief executive of marketing firm CitizenMe, believes consumers should be given the ability to control and monetise their data.

On his app, consumers take personality tests and quizzes voluntarily, then share that data anonymously with brands looking to buy more accurate marketing data to inform their advertising campaigns.

"Your data is much more compelling and valuable if it comes from you willingly in real time. You can outcompete the data brokers," he says.

"Some of our 80,000 users around the world are making £8 a month or donating any money earned to charities," says Mr Deakins.

Brands - from German car makers to big retailers - are looking to source data "in an ethical way", he says.

"We need to make the marketplace for data much more transparent."

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external