'It's a hacker's paradise out there'

- Published

Beware of connecting an aquarium to your computer network

In what could have been the plot of a Hollywood heist movie, the hackers took great interest in the vast aquarium that a Las Vegas casino had installed in its lobby.

The casino's owners thought that the huge fish tank was an impressive sight that helped create a classy ambience as people arrived.

What they failed to realise was that the aquarium was an easy way to break into the casino's computer system, and the hackers pounced.

For while the casino had protected its IT network with the usual firewalls and anti-virus software, staff forgot that the futuristic fish tank was connected to its system so that the water temperature and quality could be automatically monitored.

So criminals trying to get their hands on the bank details of the casino's wealthiest gamblers were able to hack into the network via the aquarium.

Thankfully for the unnamed casino, and in a stroke of good timing, it was just about to try out a new Anglo-American cyber security company called Darktrace that quickly spotted the breach.

"We stopped it straight away, and no damage was done," says Darktrace chief executive Nicole Eagan. "But as more and more electrical items are connected to the internet it is a hacker's paradise out there."

Nicole Eagan is a computer industry veteran

Ask most companies who their founders and key staff are and they happily reel off a list. But Darktrace, which was set up in Cambridge, England, in 2013, has to be a bit more discreet.

This is because some of the company's co-founders, and many of its 650 employees, are former spies. They have joined the business from the likes of UK intelligence agencies such as MI5, MI6 and GCHQ, as well as the US's Central Intelligence Agency.

While such men and women bring obvious security skills, Darktrace also employs a large number of advanced mathematicians who take the lead on developing Darktrace's cyber security software.

"We are a mixture of spooks and geeks," says Ms Eagan, 52, the firm's American boss.

The company was created five years ago when former MI5 and GCHQ operatives were brought together with mathematicians from Cambridge University by London-based technology investment fund Invoke Capital.

The idea from day one was to utilise artificial intelligence (AI) or machine learning to improve cyber security. This all sounds very complicated, but in very simple terms it means that Darktrace's software systems are programmed in such a way that they can learn and update themselves.

And rather than simply looking for a virus, they constantly monitor a company's computer system to look for abnormal patterns or behaviours.

Darktrace hires former spies from security services such as the UK's MI6, which is formally known as the Secret Intelligence Service

Ms Eagan says inspiration comes from the human body's immune system.

"Just like the human body, computer systems have a skin or firewall that keeps most things out, but occasionally a bacteria or virus gets in," she says.

"Our immune system then has to respond. It has an innate sense of self and it isolates what is not self, and it has a very rapid and precise response to it. That is exactly how Darktrace works."

Now valued at more than $800m (£580m) after a number of rounds of investment from venture capital firms, Darktrace's 5,000 business customers include telecoms firms BT and Telstra, global banks, airports, power companies, and multinational retailers.

"We are finding seven threats a minute across our customers at the moment," says Ms Eagan.

"The attacks are a mix. It can be criminals or a national state, or an intermixing of the two.

"Or it can be a disgruntled employee, such as someone trying to upload data when they leave."

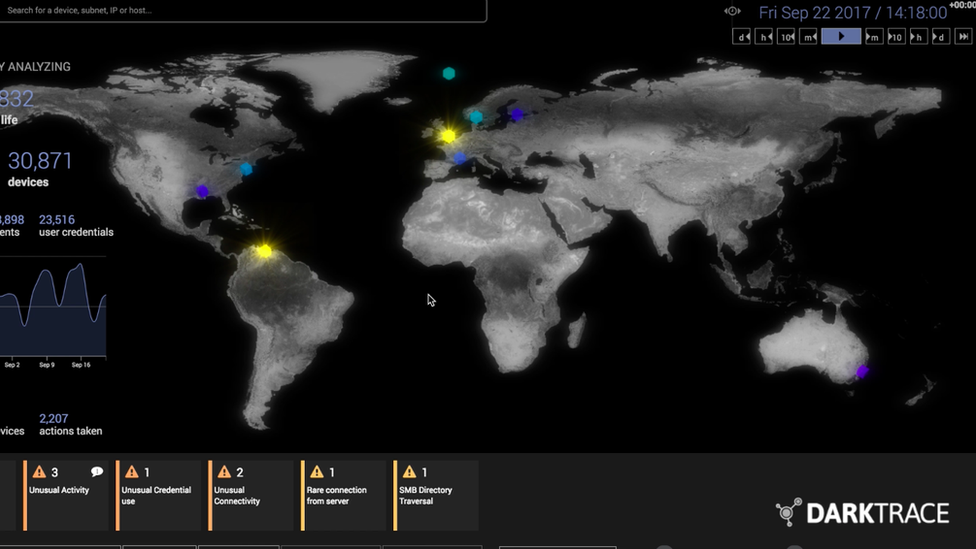

Darktrace says it has to deal with seven threats to its customers every minute

Cyber security expert Prof Alan Woodward, from Surrey University's computer science department, says while Darktrace is not the only cyber security firm now utilising AI, it is "in pole position" to be the market leader.

"There is a little bit of an arms race in cyber security, and AI is at the forefront of that.

"Traditionally in cyber security you had to know what the virus looked like in the first place in order the spot it," he says.

"But by using machine learning you are looking for malicious behaviour, or the early effects of the virus rather than spotting the virus itself, so the aim is to be able to react more quickly."

In its last financial year Darktrace had revenues of £31m. At the same time it made an undisclosed loss, but Ms Eagan says this was only because the company was continuing to heavily invest in its growth. "We could become profitable at any time," she says.

Darktrace says companies are facing attack from nation states

Ms Eagan doesn't herself come from a security service or maths background. Instead she was somewhat of a child prodigy in computing.

Growing up in New Jersey, she was an avid programmer as a teenager after her dad bought one of the first IBM home computers.

She went to university when she was just 16 to do a joint degree in computer science and marketing.

Five years on Wall Street followed, where she built computer systems for some of the largest banks, before she was poached by software giant Oracle and moved to California.

Darktrace monitors cyber attacks around the world

After a number of years with Oracle she moved into venture capital, becoming a founder at Darktrace in 2013, and then its boss a year later.

"Thanks to my background I was able to immediately grasp and understand the technology at Darktrace," she says. "And I can have meaningful and deep conversations with our chief technology officer and customers."

More The Boss features, which every week profile a different business leader from around the world:

Darktrace now has twin head offices in Cambridge and San Francisco, and 30 others around the world.

This means a lot of travel and staying in hotels for Ms Eagan. But one thing she never does is connect to guest wi-fi systems.

"I'm like 'don't do it, don't do it'. You just don't know what security system if any is protecting it, so you are putting yourself wide open to possible attack."