Polluted Paris steps up war on diesel

- Published

The air quality in Paris can be poor

From the narrow streets of Montmartre to the imposing majesty of the Arc de Triomphe and the fine art on display in the Louvre, Paris has a reputation for beauty and culture.

It's just a shame about the diesel fumes, frequently so thick you can taste them.

The city is crowded, its boulevards are too often choked with traffic, and its air is badly polluted. There are times when its monuments are difficult to see through the haze.

The Mayor of Paris, Anne Hidalgo, has made tackling pollution a centrepiece of her socialist administration. Her strategy involves phasing out older vehicles and getting rid of diesels, while offering generous subsidies for other forms of transport.

What do Parisians think of moves to improve its air quality?

The policy is not universally popular. It faces opposition from motorists' groups and even regional politicians. But as cities across Europe struggle with similar pollution problems, it could yet provide a template for others to follow.

Dangerous air

According to a study carried out in 2016 by France's national health agency, external, air pollution is responsible for 48,000 deaths a year across France.

Paris itself has suffered a series of damaging smogs in recent years, particularly in winter. While vehicles are not wholly responsible for the dirty air, they do play a very significant part, external.

During the worst periods, the authorities have experimented with emergency measures - banning one in every two cars from entering the city and lowering speed limits, for example. Recently, a more refined scheme, known as Crit'Air, has been introduced.

Mayor Anne Hidalgo has made tackling pollution a priority

Cars are now classified according to their emissions and forced to display coloured stickers. This allows the authorities to issue targeted bans against the most polluting vehicles. Other French cities, including Grenoble, Lyon, Strasbourg and Toulouse, have joined in.

But it's the long-term strategy which is arguably more significant. Step by step, the city is trying to rid itself of petrol and diesel cars, and persuade people to use other types of transport.

Bans and fines

So far it has banned all conventional cars built before 1997 from entering the city centre on weekdays between 8am and 8pm. Diesels registered before 2001 are also prohibited. Drivers breaching the bans face heavy fines.

Next year, the restrictions will be widened to include pre-2005 diesels. The clampdown will then continue in stages. Diesels are due to be outlawed altogether in 2024, and petrol cars in 2030.

Sometimes it can be hard to see some of Paris's iconic monuments through the smog

It is a more aggressive strategy than that pursued by London - which has so far stopped short of actually banning older and dirtier cars, in favour of charging them extra to enter the city centre.

Paris is also steadily squeezing the amount of space available to cars by building extensive bus lanes and cycle tracks. A two-mile (3km) stretch of what used to be a major transport artery along the river Seine was closed to traffic in 2016 on a trial basis, and remains off-limits.

Big incentives

But with the big stick has come a sizeable carrot. Earlier this year, the city council extended an already-generous package of subsidies aimed at encouraging people to choose other forms of transport.

Individuals can now claim benefits worth up to €600 (£522), to help them buy a bike, obtain a public transport pass, or join a car sharing scheme - but only if they agree to scrap their cars or motorbikes. Small businesses can claim up to €9,000 towards the cost of an electric truck or bus.

Paris is cutting down space available to cars

There are also substantial grants to help taxi drivers buy environmentally-friendly vehicles, and to subsidise the installation of electric charging points.

The man overseeing all of this is deputy mayor Jean-Louis Missika.

Sitting in his opulent, wood panelled office in the City Hall, he explains why he is happy to take drastic action.

"We are in a situation of emergency, the shift towards clean mobility and the diminution of the number of cars is very urgent. We need to do something - it is a question of public health."

Mr Missika believes his strategy will also benefit the Parisian economy, because he thinks a reduction in traffic and pollution will make the city more attractive to businesses, which might otherwise go elsewhere.

Taxi drivers will get financial help to switch vehicles

The city has, however, suffered one major setback. Its showpiece Vélib cycle hire scheme - which has been copied by cities around the world since its launch in 2007 - has run into trouble.

Last year a new operator, Smovengo, won the contract to provide the service for the next 15 years. But its attempts to introduce new, high-tech electric bikes have so far been beset with problems, creating a scandal dubbed "Vélibgate" by the French press., external

Motorists resist

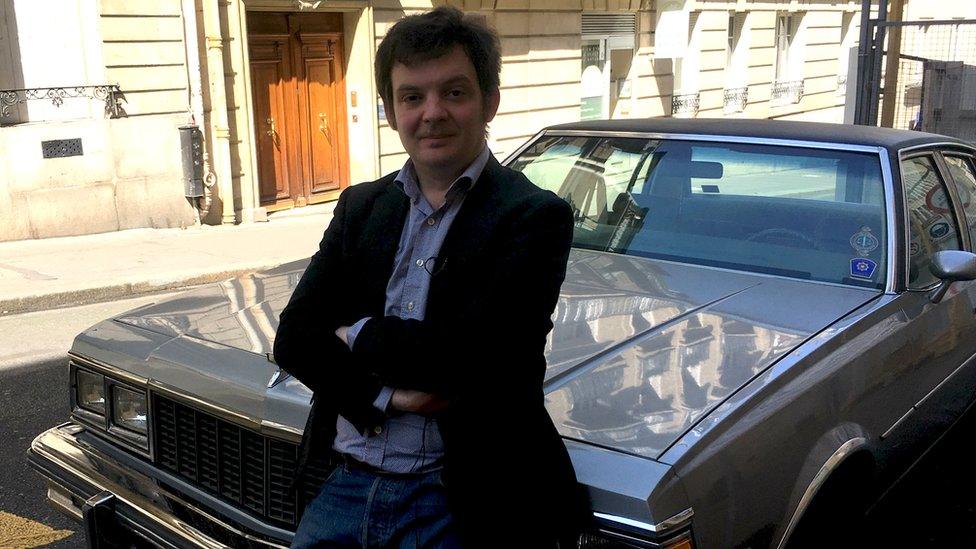

But not everyone agrees with the clampdown on cars. Julien Constanti is a lawyer acting on behalf of a motorists group, the Fédération Francaise des Automobilistes Citoyens.

Driving around the crowded streets in his own car, a colossal 1979 Chevrolet of the kind once favoured by US police, he tells me the policy discriminates against people who cannot afford to replace their old cars.

I ask him if he thinks Paris has declared war on the motorist.

"Yes, and it's not just the city of Paris," he replies.

"It's also on a state level, and possibly on a European level. It's like, you have to buy cars to make the economy work - but don't use them!"

Julien Constanti argues that the city's policy amounts to discrimination

It is true that some other European cities have shown a marked enthusiasm for getting rid of cars.

Oslo and Madrid, for example, are both planning to make central areas off-limits to motor vehicles within the next few years. Hamburg is also taking action to get rid of older vehicles.

As cities across the continent struggle to meet EU air quality standards, the likelihood is many more will introduce similar restrictions.

So residents, commuters and businesses in urban areas across Europe may soon have to learn new ways to get around.

- Published29 March 2018

- Published8 March 2018