Saving flood water to get through the droughts

- Published

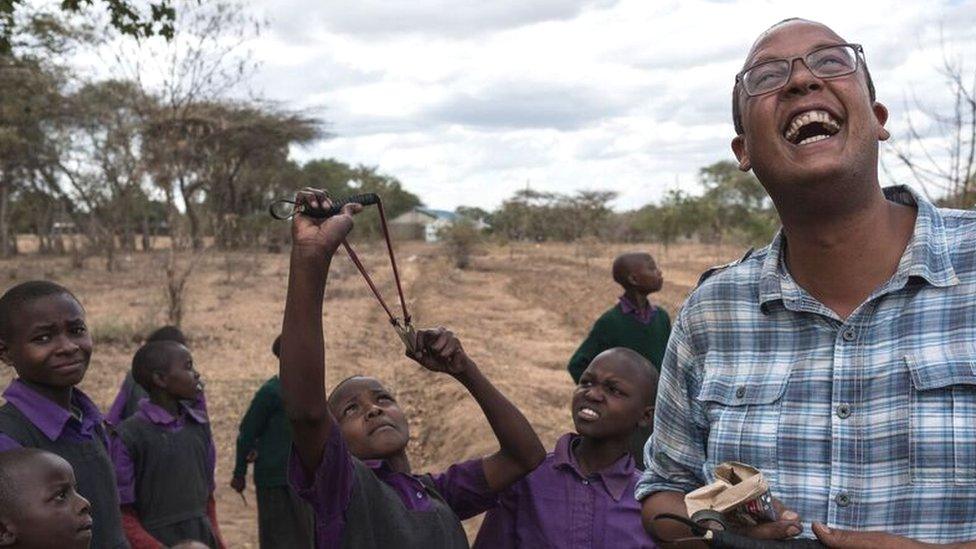

Biplab Paul, co-founder of Naireeta Services, designed the bhungroo to help farmers ride out India's droughts

Erratic rainfall and prolonged dry seasons in many parts of India mean that farmers often have to struggle with waterlogged fields or droughts, which can ruin their crops.

Many are ultimately forced to quit the land and migrate to find other work.

"Once our whole family used to work here, and we used to make our livelihood from agriculture," says Madhiben - the family's fields are now covered in a thin white sheet of salt.

"They all used to be lush green, now it's all white desert," says Madhiben, who lives in a village in Gujarat in north-west India.

Many parts of India are showing severe effects of desertification but now one social enterprise, Naireeta Services, is taking action. Co-founders Trupti Jain and Biplab Khetan Paul have come up with an answer to this.

"During the Gujarat earthquake of 2001, I remember how temperatures rose drastically leaving people without water, followed by monsoons, which flooded everything and left farms waterlogged for months. That's when I started looking for a solution" says Biplab.

"Later I realised that these erratic rains could be a solution for such dry seasons."

High levels of salinity can create an impermeable layer which prevents water from penetrating the soil

Biplab and Trupti then started experimenting with different structures to store excess rain water so that it could be used in dry seasons.

"That's when we innovated bhungroo - a water harvesting technique that uses an injection module to store excess rain water underground. Farmers can then use the same water for irrigation during summer and winter," says Trupti.

Encroaching deserts

The high level of salinity in many regions of Gujarat and other states of India often creates an impermeable white or brown layer that prevents water from penetrating the soil, leaving the surface waterlogged.

"This standing water adds to the salinity as many minerals present in the soil also get dissolved in the water, which in the dry season creates a salty layer," says Biplab.

Each year, 12 million hectares (29 million acres) of land are lost to encroaching deserts. That's land where 20 million tonnes of grain could have been grown.

People living off the land often feel they have no choice but to migrate.

The bhungroo allows excess water to flow directly flows into the underground aquifer, says Trupti Jain

"After the monsoons our fields remain waterlogged for up to three months. Because of that, salts accumulate and in summers, there is no water," says Madhiben.

"Now all males of our family have had to move to the cities to get work."

According to the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) by 2030, 135 million people could lose their homes and livelihoods to desertification.

"In India, five million small holder farmers are affected with salinity, flood and drought problems - and across the globe 650 billion hectares of land gets affected with these issues," says Trupti Jain.

Bhungroo irrigation

Bhungroo is a Gujarati word meaning "straw" - a pipe between 10-15cm (4-6in) diameter is inserted into the soil at places where waterlogging is a problem.

So during monsoons. the excess water drains down the pipe, gets filtered, and then flows down to natural aquifers deep below the soil where it can stay until it is needed during the dry seasons.

Kesar Behan (left) says her income has tripled since she installed a bhungroo on her farm

It means that in the monsoon season farmers can grow crops because their land is not too wet. In the dry seasons of winter or summer they can use pumps to draw up the stored water and irrigate their land, says Trupti.

"Due to heavy rains during monsoons, followed by a dry spell in summers we used not to have any crops - and then we had to go to other areas of Gujarat for work," says farmer Kaser Behan.

But now she and her family have a bhungroo, "we can easily grow two crops in a year".

One bhungroo unit can irrigate up to 8-10 hectares, and construction costs can vary from $750 to $1,500 (£1,100) depending upon the location and size of the project.

"Our enterprise is working on hybrid models that mean we are mobilising grant money as well as generating a profit to sell our bhungroo to the customers," says Trupti.

"Talking about the grant money, we are mobilising to support the poor farmers who cannot afford the cost of the bhungroo."

One bhungroo unit can irrigate up to 8-10 hectares

So far, Naireeta has constructed more than 3,500 bhungroos across India and beyond, and says its aim is "antyodaya", a word used by Mahatma Gandhi that means serving the last person in the queue in the best possible way.

"In rural India, the last person is the smallest landholder who does not have any water service for his or her crop," says Trupti Jain.

Part of our series Taking the Temperature, which focuses on the battle against climate change and the people and ideas making a difference.

This BBC series was produced with funding from the Skoll Foundation

- Published18 May 2018

- Published11 May 2018

- Published16 May 2018

- Published27 April 2018

- Published20 April 2018