Does the UN mean anything to the young?

- Published

The UN is going to run global surveys to find the issues that are important for young people

The United Nations wants to gain a much better idea of what young people are thinking - and to stop feeling "paternalistic" and out of touch.

Senior UN officials are going to launch a global, information-gathering poll four times a year, to take the temperature of the opinions of the young on issues such as education, family life and the internet.

Michael Moller, director-general of the United Nations Office in Geneva, said governments and institutions like the UN have not listened enough to young people.

"I am 65 and there are very fundamental differences in how people see themselves when they are 15 and when they are 65 - my generation cannot assume what the younger generation wants," said Mr Moller.

'Paternalistic'

He says that promises set out by the UN and the international community - like the "sustainable development goals" - need to be informed by the views of young people.

"The paternalistic approach to development does not work any more," said Mr Moller.

Michael Moller, at the back, says the UN needs to stop assuming it understands views of the young

"Asking these kids regularly what they think means that we get a serious database of knowledge of what young people across the world think about their lives, what are their dreams and aspirations."

There has been a pilot for this United Nations' Global Youth Poll, which is going to survey more than 25,000 people, aged 10 to 29, in 26 countries.

The first findings of the pilot poll, run by the UN Global Sustainability Index Foundation, has been that 63% of young people do not enjoy school or university.

Young people in the US and UK are most unhappy in education, with dissatisfaction levels at 71% and 70% respectively.

By contrast, 49% of Mexican students and 44% of New Zealanders enjoy school.

Family attitudes

The poll reveals differences in how young people in different countries relate to their families - young people in Africa and Asia countries are more positive about spending time with family than Europeans and Americans.

In the UK, 32% of young people actively dislike spending time as a family, whereas 69% of young Vietnamese enjoy it.

Young people in the UK are less likely to want to spend time with their family, suggests pilot survey

The poll found that young people in the US reported having the worst year in 2017 - a quarter said it was a bad year for them, while kids in Austria had the best year.

The data will give the UN a more reliable measure than ever before for comparing how government policies are actually affecting young people, according to the poll's designer Professor Dan Cassino of Farleigh Dickinson University in the US.

Michael Moller and the UN want to find how young people view education

It lets the UN compare how countries are performing by the same metrics, and avoids the danger of statistics being manipulated.

He said it will give a deeper assessment of the actual impact of policies, beyond simply looking at the amount of money invested, which ignores waste, fraud and inefficiencies.

And children's brutal honesty means they often provide more reliable survey results than adults.

'Throwing spaghetti'

"The advantage is that children don't have a filter, they don't mind telling you the truth even if it's politically inconvenient or it puts them in a bad light or if they think it's what the researcher wants to hear," said Prof Cassino.

"Children are great as survey respondents simply because they don't care what you want to hear, they are going to tell you it what they think whether you like it or not."

Dan Cassino says children can be brutally honest in their views

Prof Cassino hopes the frequency of the poll, and the possibility of direct comparison with other countries, will encourage governments to "act quickly to correct emerging problems, or emulate successful approaches".

"When a government rolls out a new programme, normally we wait five years to see what the outcomes are," he said.

"But now we should be able to see result on the ground in three or six months and that will let governments test a lot of new things, throw a lot of spaghetti at the wall and see what sticks."

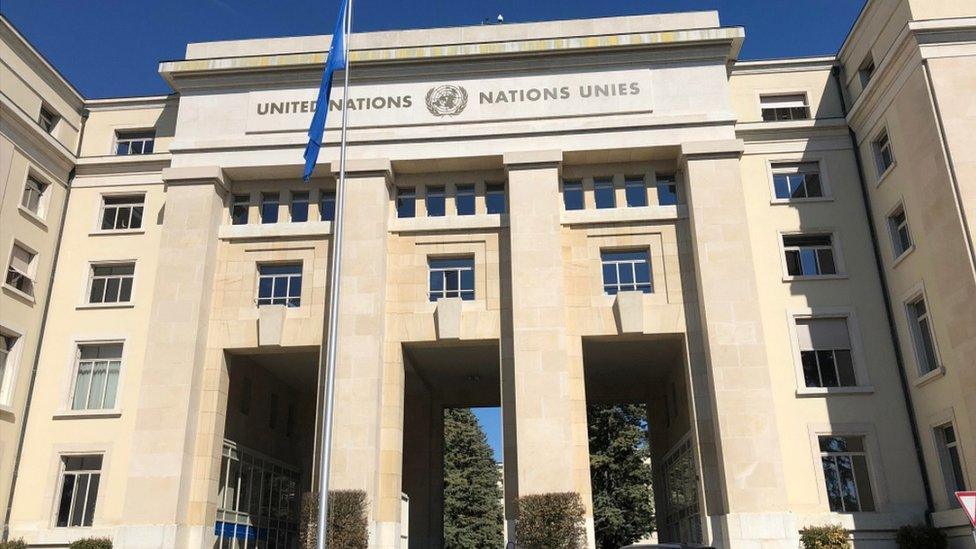

The United Nations in Geneva wants to keep relevant to the next generation

Mr Moller also warned that in preparing for the future, education systems must prepare for a continued rise in migration.

"Climate change is going to put tens if not hundreds of millions of people on the move in the next decades and the world isn't ready for that, not even close," he said.

"Many of these will be young people - the average age in some African countries is 14 or 15 - and these kids need to be educated to be able to survive, have a job, create a family, and have a meaningful life."

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk