Making food crops that feed themselves

- Published

Three times a year, Vietnamese farmers transplant rice seedlings out into the paddy fields

By 2050, the world's population is expected to reach 9.8 billion. With limited land, and intensive farming already causing irreversible environmental damage, how can we feed the world without exhausting its natural resources?

All over Vietnam it's transplanting season. In every direction farmers with their famous conical hats are pushing tiny rice seedlings deep into the mud.

Rice farming is essential for Vietnam's food supply and economy, but such a booming industry comes with an environmental cost.

Farmers are dependent on nitrogen-based fertilizers to boost yields. But excess nitrogen can wash away, polluting rivers and oceans, as well as evaporating into the atmosphere.

Within the last decade, women have taken over running the fields, as men have left to earn more working in construction

Travelling two hours southeast of the country's vibrant capital Hanoi, I arrive in the Tien Hai.

This modest farming town is host to an international research trial, investigating whether a strain of nitrogen-fixing bacteria can help to reduce the amount of fertilizer used by farmers.

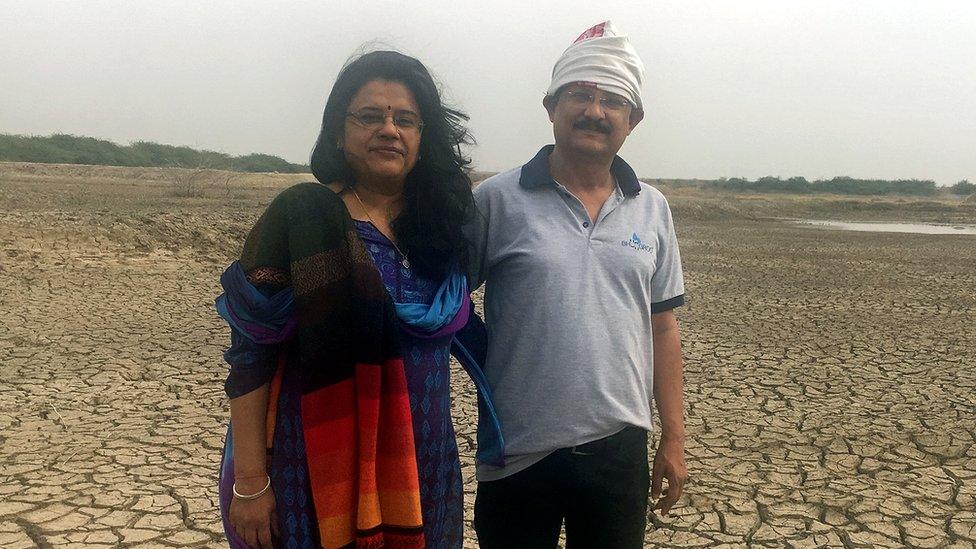

Leading the field trial is Dr. Pham Thi Thu Huong, from the Field Crop Research Institute.

"Rice, like other crops relies on getting its essential nutrients from nitrogen fertilizer, but over 50% of the fertilizer used either evaporates, or washes away," explains Dr. Huong.

"It forms nitrous oxide which is 300 times more harmful than carbon dioxide as a greenhouse gas."

Dr. Pham Thi Thu Huong, from the Field Crop Research Institute in Vietnam

For Dr Huong, transplanting the 15 day old rice seedlings from the lab out into the field is her first chance to examine the difference in length and weight between the treated and untreated seedlings.

As seeds, the treated plants are coated in nitrogen-fixing bacteria. Normally found in sugarcane, these bacteria enable the rice plants to extract nitrogen directly from the air, instead of being reliant on artificial fertilizer.

"As the plant grows, an aerobic relationship between the bacteria and the rice plant develops" says Dr. Huong. "This allows the bacteria to take nitrogen straight from the atmosphere in a form the plant can use."

After 15 days incubation the treated and untreated rice seedlings are compared before being transplanted to the field.

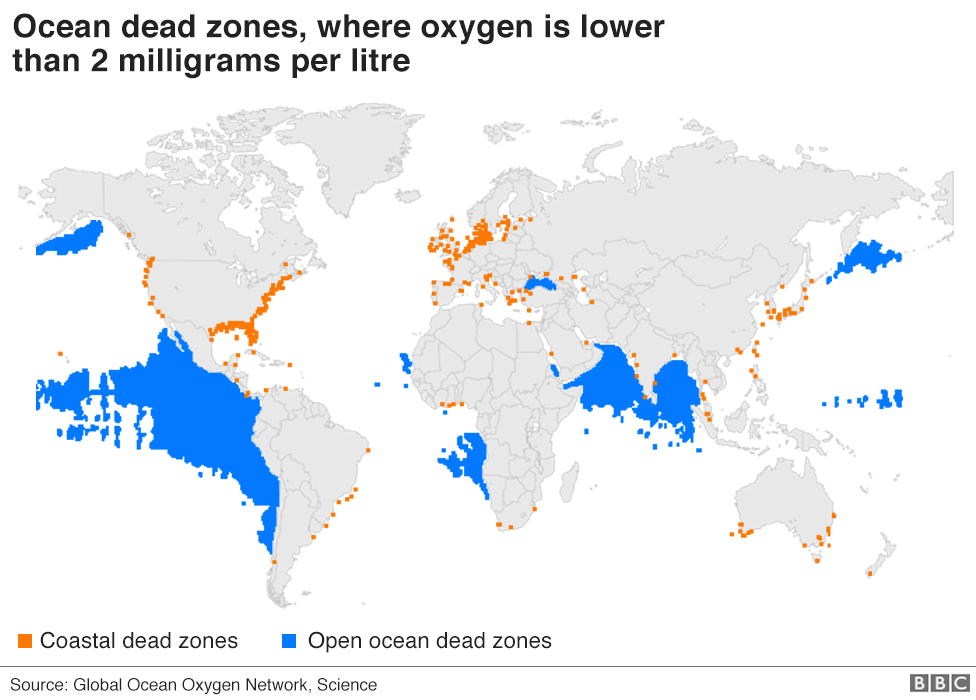

'Dead zones'

The 'Green Revolution' of the 1960s prompted worldwide use of nitrogen-based fertilizers and pesticides.

The boost in global food production saved millions of lives from the imminent threat of famine.

However, the excessive use of fertilizers has continued to be so inefficient, more nitrogen is pouring off into the waterways and oceans than ever before.

Excess nitrogen causes 'dead zones' by unleashing algal blooms, which then rot and consume all available oxygen, suffocating other marine life.

Today there are more than 500 dead zones in the world's oceans, a figure that has quadrupled in the last 50 years.

The farmers

Three times year, Vietnam's millions of famers transplant tens of millions of seedlings into their waterlogged fields.

Living off an annual income of just $1300 dollars, Bui Thi Suot relies on the success of her crops to support her family.

"We are aware of the pollution and the environment, but our crops need fertilizers. We are farmers, we don't have any other choice" says Bui Thi Suot.

During the rice season Bui Thi Suot gets up at 4am everyday, to transplant the seedlings, remove any weeds, and apply fertilizers and pesticides.

A 'super bacterium' solution?

With half the world's crops and farmers depend on synthetic fertilizer, how can we feed the world's growing population without causing further harm to the environment?

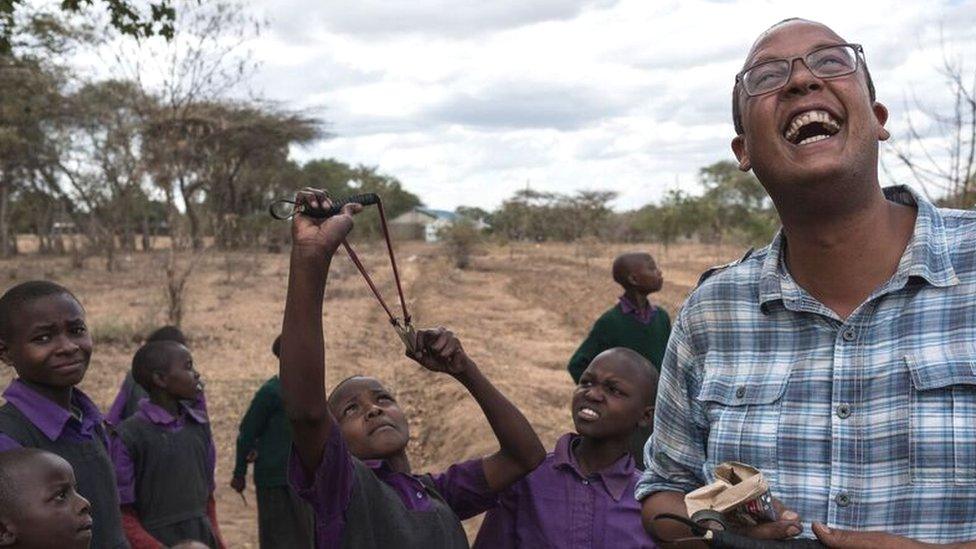

Dr. Huong's trial in Vietnam is just one part of a global network of scientists and entrepreneurs hoping nitrogen-fixing technologies can be a part of the solution.

Bioscientist Dr. Ted Cocking, from the Centre for Crop Nitrogen Fixation in the UK, was the first to unlock the potential of this unique bacterium - Gluconacetobacter diazotrophicus, or Gd for short.

Effective in the laboratory, Dr. Cocking's ambition was always to get this technology out into the field.

In 2011, he paired up with entrepreneur Peter Blezard. Together they started a company called Azotic, one of the funders behind Dr. Huong's rice trial in Vietnam.

Mr. Blezard hopes Azotic will begin selling the 'super bacteria' in liquid and powder form, on the US commercial market from next spring.

"Currently we are focusing on corn and soya crop trials in the US and Europe, and rice trials in Vietnam, Thailand and the Philippines," says Mr. Blezard.

"In Vietnam, we seeing up to 50% reductions in nitrogen fertilizer, combined with a 15% increase in rice yields."

Dr Huong adds the nitrogen-fixing bacteria suspended in a solution, to water. As a part of the treatment process, the rice seeds will be left to soak in the solution.

But not everyone is as convinced.

Microbiologist Dr. Tim Mauchline from the Rothamsted Research in the UK, doubts this technology can be replicated in all crop varieties, all over the world.

"The world is a big place with different climates, weather patterns, crops, and soil types," he says.

"To think there's one silver bullet that can solve all of these problems, this would be fantastic, but I will be surprised if it is the case."

The population of Vietnam's capital city Hanoi is expected to reach 8 million by 2020

Dr Huong has discovered, even within the optimum conditions of the trial, some rice varieties are proving more responsive to the bacteria than others.

However, for Dr Huong, precision and patience are finally paying off.

"The first trial was a complete failure, but we brought the bacteria back into the lab and tested it repeatedly until we got the formula right", she says.

"I hope my work will help to ensure global food security, at the same time as preserving and protecting natural resources."

During the rice season farmers work long hours. They have a short window of opportunity to transplant millions of seedlings out into the fields.

This BBC series was produced with funding from the Skoll Foundation.

Part of our series Taking the Temperature, which focuses on the battle against climate change and the people and ideas making a difference.

Photos: Derrick Evans and Ly Truong

- Published1 June 2018

- Published25 May 2018

- Published18 May 2018

- Published11 May 2018

- Published16 May 2018

- Published27 April 2018

- Published20 April 2018