Why we no longer love department stores

- Published

- comments

Department stores were once the main attraction on many High Streets, but these days shoppers appear increasingly able to resist their charms.

House of Fraser has just announced it intends to close 31 shops, affecting 6,000 jobs, as part of a rescue deal.

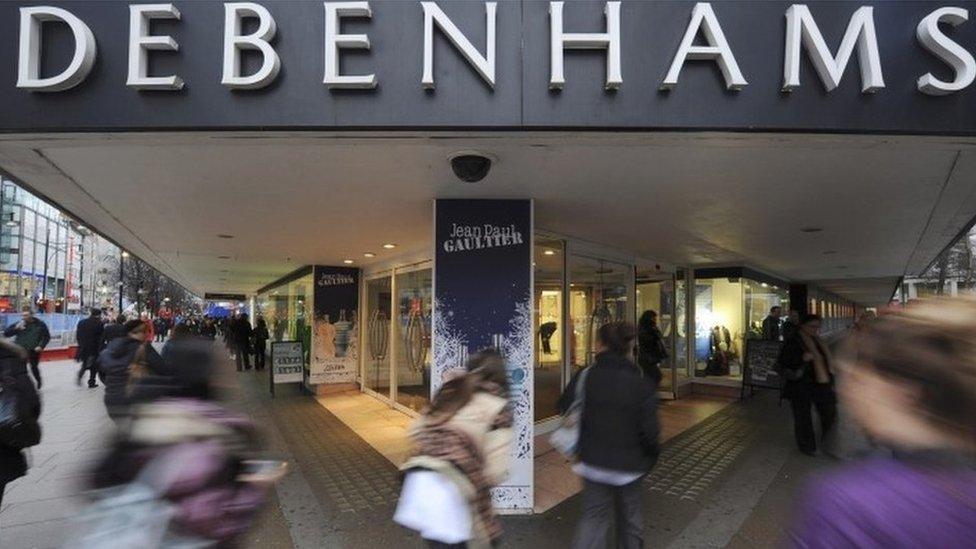

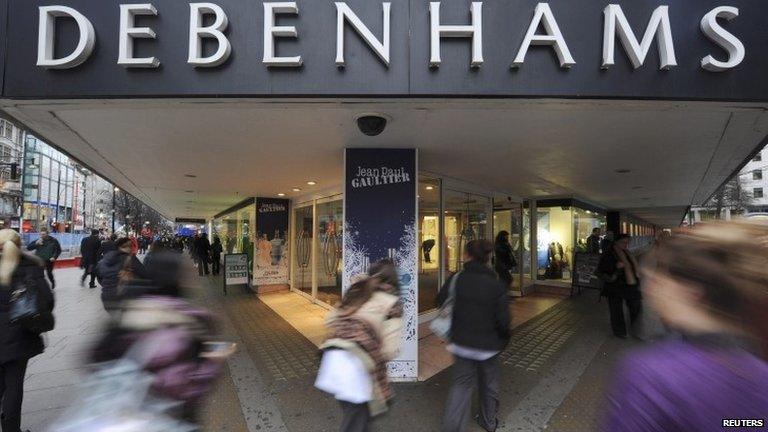

Debenhams is planning to shut stores as profits fall - and BHS spectacularly collapsed in 2016, putting 11,000 people out of work.

Yet some chains continue to prosper, so where have the weaker performers gone wrong?

1. Lack of investment and innovation

Diane Wehrle of market research firm Springboard says the worst department stores "haven't changed in 10, maybe 20 years".

This is because they have not invested enough in upgrading their shop floors, product ranges or online offerings.

"As we have had access to global products our standards as consumers have increased - we can also buy anything we want online," she says.

"So if we are to go shopping we need to have a good experience, excitement and entertainment. A lot of today's department stores don't supply that."

Ms Wehrle adds that their unique selling point - offering a host of different brands under the same roof - has also been weakened in the internet age.

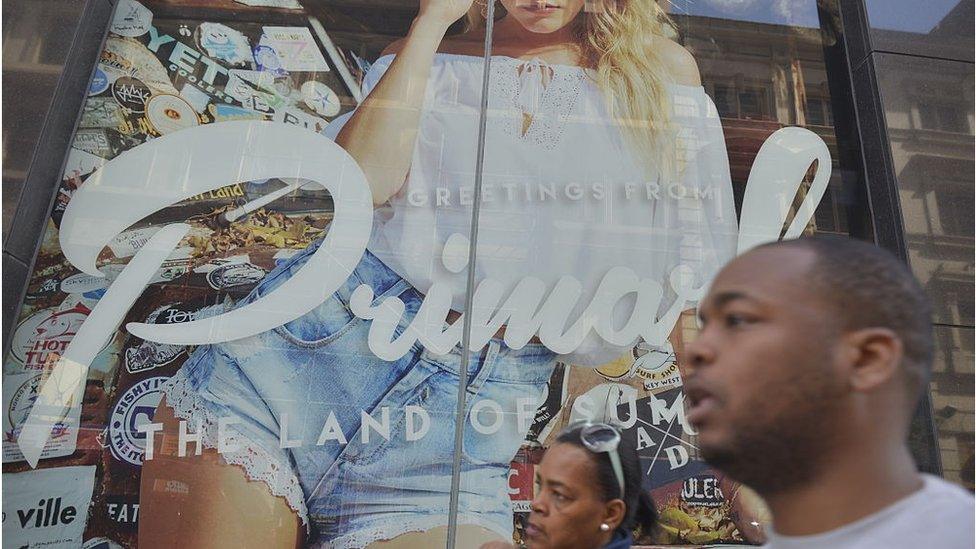

We are buying more of our clothes from fast fashion retailers like Primark

2. Out of fashion

Many of today's ailing department stores focus on fashion - but they may not have the right merchandise, says Stephen Springham, head of retail insights at Knight Frank.

"It's a part of the problem at Debenhams which hasn't kept up with the times," he says.

"The range isn't terrible but it's a very competitive market and being not terrible is not good enough."

Meanwhile, Mr Springham says most of House of Fraser's goods are "other brands you can buy somewhere else", while their in-house brands are not particularly strong: "There isn't that point of difference."

It comes as more shoppers, both young and old, are buying their clothes from nimbler "fast fashion" retailers such as Asos, Primark and Zara that can also beat them on price.

3. Too much discounting

As sales have fallen, some department store groups have turned to discounting in a bid to keep tills ringing.

But Ms Wehrle says that approach has not worked and has become a "vicious circle".

"Others do it too so you have to go lower, and it becomes a race to the bottom."

This squeezes margins, leaving department stores with even less to spend on improving their shops.

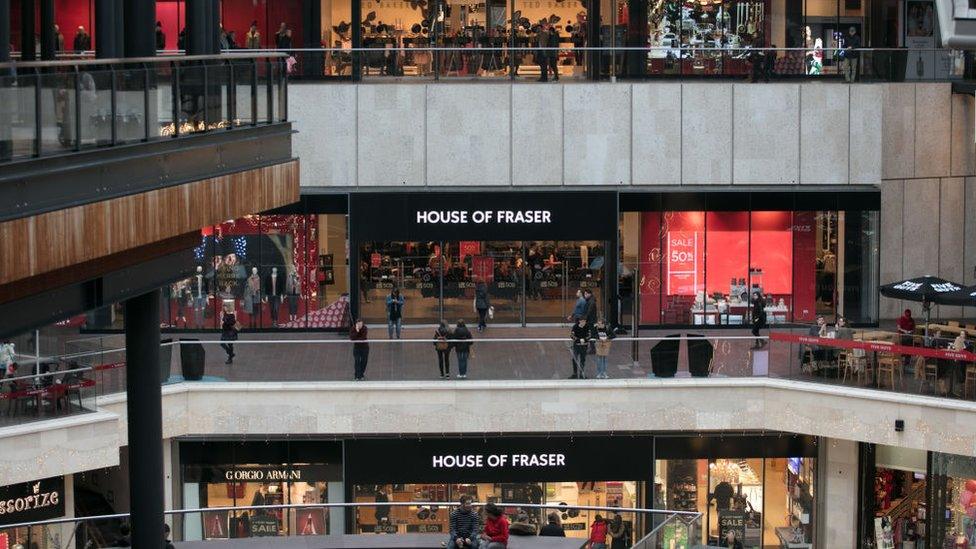

Some House of Fraser stores are more modern than others

4. Hard to navigate stores

Like other struggling high street retailers, some department store groups have too many underperforming shops and need to downsize.

Debenhams, which has 176 UK stores, has said it could close 10 outlets and is in talks with landlords about reducing space at 30 more.

And House of Fraser, which had 59 stores, is now planning to close more than half of them.

Downsizing isn't easy, however. Many of the biggest department stores are locked in very long leases of "30, 40, even 50 years", says Mr Springham.

Making matters worse, some of the buildings housing them are ill configured for a modern retail experience, he added.

"Some of them are more than 100 years old and quite higgledy-piggledy … they might not have a centralised escalator. If you built them from scratch you wouldn't build them that way."

Selfridges reported strong sales last year

5. High Street slowdown

These problems come amid a general slowdown on the High Street linked to weaker consumer confidence, online competition and rising overheads such as a higher minimum wage.

But Ms Wehrle believes struggling department stores could have weathered the storm better: "If a retailer blames the demise of their business on these pressures alone they are probably hanging by a thread."

She points to John Lewis as an example of a group that has adapted well in changing times by ramping up its online presence and investing in its store experience.

Selfridges and Harrods, which target well-heeled shoppers, many of them from abroad, are also doing well.

For the year to January, sales at Selfridges rose 16% to £1.6bn, while Harrods posted a 23% surge to £2.1bn.

- Published4 June 2018

- Published20 April 2017

- Published19 April 2018