Will the G7 summit be dominated by a trade row?

- Published

It won't be a very comfortable G7 summit.

Leaders from the biggest developed economies meet in Canada at the weekend against a background of increasing tension about trade.

New US tariffs (taxes applied to imports) on steel and aluminium affect all the other G7 members: the UK, Germany, France, Italy, Japan and the summit's host.

Retaliation is in the air.

The European Union, representing four of the G7 nations, and Canada, have their plans in place and are ready to hit American goods with extra tariffs in early July.

There are also complaints to the World Trade Organization (WTO) in the pipeline, which allege that the US action breaches WTO rules.

Of course it is not unusual for there to be differences among the participants at any summit, the G7 included.

But President Trump does represent something new in, among other things, his approach to international trade.

It is a dramatically different one to that of his predecessors.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau will host the G7 summit

For much of the period since the late 1940s, the US has been one of the most important driving forces behind multilateral efforts to lower barriers to international commerce, first through the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade and then, from 1995, through the WTO.

Three-quarters of a century after this process began, the US has one of the lowest levels of tariffs of any WTO member. (Not the lowest of all, as some US officials have claimed. Hong Kong has no tariffs at all.)

The US approach has previously been in line with the view of the great majority of economists that all countries gain from trade liberalisation.

In fact, most take the view that countries benefit from lowering their own trade barriers, as that reduces prices for consumers and businesses that use imported goods.

But some people do lose from trade liberalisation, for instance, in industries that become more exposed to competition, such as textiles and furniture producers in developed economies (although technology has also been an important factor affecting employment in those industries).

That means it's politically easier to sell trade liberalisation if there are new opportunities for exporters to compensate.

Will the real leaders be all smiles after the G7 discussions?

The view in the White House has changed. President Trump appears to regard trade as an area where countries either win or lose, measured by whether exports are greater than imports.

Because the US has a trade deficit (it imports more than it exports) he sees it as losing, and that, he believes, is the result of bad deals done by previous administrations.

He also parts from his predecessors in having no enthusiasm for multilateral negotiations, preferring bilateral, one-to-one deals.

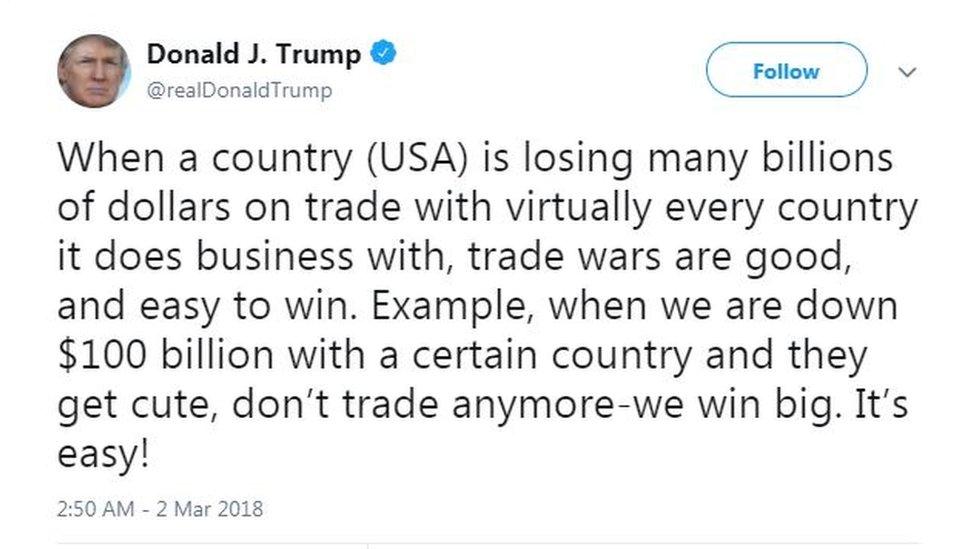

And he has shown a much greater readiness to use trade barriers to force concessions from trade partners exemplified by his tweet about trade wars being easy to win: "When we are down $100 billion with a certain country and they get cute, don't trade any more - we win big. It's easy!"

The steel and aluminium tariffs cast a dark shadow as the G7 meet.

President Trump justifies the measures in terms of national security, a need to reduce the dependence of the US military on imports of the metals.

The EU, in particular, doesn't believe that and its response reflects a view that the US measures are protectionist. The EU's trade commissioner Cecilia Malmstrom told the European Parliament, external: "We suspect that the US move is effectively not based on national security considerations but an economic safeguard measure in disguise."

It is not the first time that major economies' leaders have played a bit fast and loose with global trade rules. But many observers see President Trump as taking this to a new level.

Under him, the US has shown some reluctance to sign up to the routine pledges to avoid trade protectionism that are usually made at summits.

At a finance ministers' meeting last year of the wider G20 group, the pledge was absent from the communique.

Later that year, the G7 with President Trump did reaffirm its readiness to fight protectionism, but the fact that there was any question about whether that would happen is a mark of how different he is seen as being.

The EU's Cecilia Malmstrom, says economics, not national security, may be the reason behind US tariffs

Meanwhile the WTO's system for ruling on trade disputes is in danger of grinding to a halt. The body which hears appeals against initial rulings could become unable to function.

It normally has seven members, agreed by the WTO countries. But the US has resisted new appointments and it currently has only four. The number is due to drop to three in September when another member's term ends. Three are needed to hear an appeal, so it will become even harder for the body to deal with its workload.

The reason for this issue? The US has refused to support new appointments. A group of law professors has warned that it could lead to the crumbling of the WTO dispute settlement system.

The mood music at the summit will not be relaxing. The other six see the global trade system that has evolved since the World War Two - a system based on the WTO, and a patchwork of free trade agreements that go beyond the WTO rules - as something worth preserving.

In President Trump, they are dealing with a leader seen by many observers as a serious threat to the future of that system.