Can we trust AI if we don't know how it works?

- Published

What's it thinking? Will AI become too clever for us?

We're at an unprecedented point in human history where artificially intelligent machines could soon be making decisions that affect many aspects of our lives. But what if we don't know how they reached their decisions? Would it matter?

Imagine being refused health insurance - but when you ask why, the company simply blames its risk assessment algorithm.

Or if you apply for a mortgage and are refused, but the bank can't tell you exactly why.

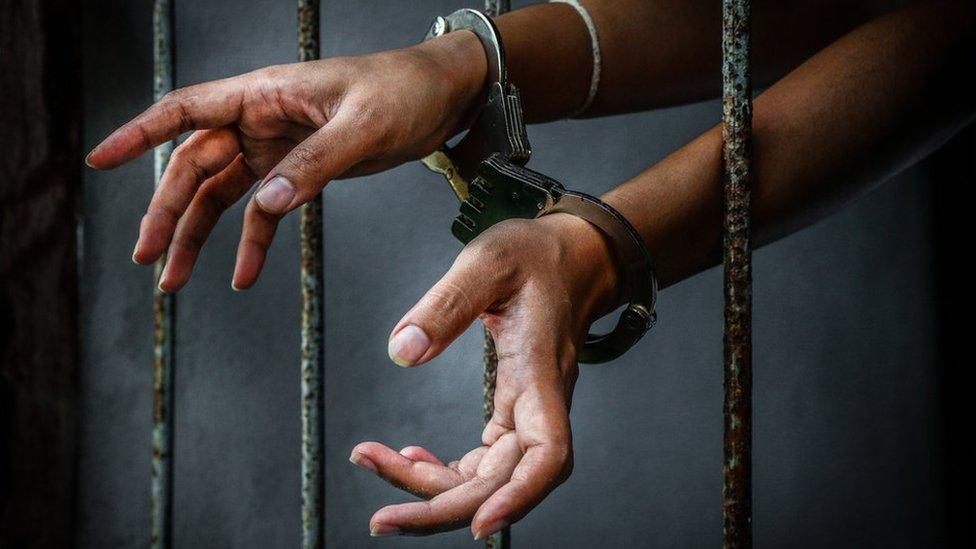

Or more seriously, if the police start arresting people on suspicion of planning a crime solely based on a predictive model informed by a data-crunching supercomputer.

These are some of the scenarios the tech industry is worrying about as artificial intelligence (AI) marches inexorably onwards, infiltrating more and more aspects of our lives.

AI is being experimented with in most sectors, including medical research and diagnosis, driverless vehicles, national surveillance, military targeting of opponents, and criminal sentencing.

A recent report by consultancy PwC forecasts that AI could boost the global economy by $15.7tn (£11.7tn) by 2030.

But at what cost? These software algorithms are becoming so complex even their creators don't always understand how they came up with the answers they did.

AI has huge potential for medicine and drug discovery

The advent of neural networks - designed to mimic the way a human brain thinks - involve large numbers of interconnected processors that can handle vast amounts of data, spot patterns among millions of variables using machine learning, and crucially, adapt in response to what they've learned.

This enables amazing insights, from better weather forecasts to the more accurate identification of cancers.

But Rhodri Davies, head of policy and programme director at the Charities Aid Foundation, says: "If these systems are being used for things like voting or access to public services, which we're starting to see, then that's usually problematic."

David Stern, quantitative research manager at G-Research, a tech firm using machine learning to predict prices in financial markets, warns that "the most rapid progress in AI research in recent years has involved an increasingly data-driven, black box approach.

Satnav systems help us avoid traffic jams; could AI manage entire transport networks?

"In the currently popular neural network approach, this training procedure determines the settings of millions of internal parameters which interact in complex ways and are very difficult to reverse engineer and explain."

Another trend in robotics is "deep reinforcement learning" whereby a "designer simply specifies the behavioural goals of the system and it automatically learns by interacting directly with the environment," he says.

"This results in a system that is even more difficult to understand."

So the industry is exploring ways that algorithms can always be understood and remain under human control. For example, US defence agency Darpa runs its Explainable AI project, and OpenAI, a not-for-profit research company, is working towards "discovering and enacting the path to safe artificial general intelligence".

This sounds sensible, but one of the advantages of AI is that it can do things humans can't. What if we end up making it less effective?

Adrian Weller thinks that if AI works well we might not always need to know how

Adrian Weller, programme director for AI at The Alan Turing Institute, suggests that the need to understand how a machine reaches its decisions will depend on how critical those decisions are. And other considerations might be more important than explicability.

"If we could be sure that a system was working reliably, without discrimination, and safely - sometimes those issues might be more important than whether we can understand exactly how it's operating," he says.

When it comes to driverless cars, or medical diagnosis, for example, having a machine that is more accurate and would save more lives could be more important than understanding how it works, he says.

"For medical diagnosis, if a system is 95% accurate on average, that sounds good - though still I'd want to know if it's accurate for me personally, and interpretability could help to understand that.

"But if we had some other way to be confident that it really is accurate for me, then I might be less worried about interpretability."

If a prison sentence were decided by AI should we have a right to know how?

On the other hand, where AI is used in criminal sentencing to help determine how long people are locked up for, it's important to understand the decision making process, he argues.

"If an algorithm recommended I be imprisoned for six years, I'd want an explanation which would enable me to know if it had followed appropriate process, and allow a meaningful ability to challenge the algorithm if I disagree," says Dr Weller.

"I agree with recommendations that we should require companies to be clear about when an algorithm is doing something, particularly if we might otherwise expect that it's a human," he adds.

Without these safeguards there is a risk people could be discriminated against without knowing why and become "extremely marginalised".

More Technology of Business

And if many of us don't even know that an AI algorithm was behind a decision that affected us, it conflicts with established principles in law, argues Mark Deem, a partner at law firm Cooley.

"If one thinks about the theory of contract, the promise, how is it that you can promise a certain outcome based upon machine-based learning, if you don't actually know precisely what is to be produced by a black box algorithm?"

To tackle the transparency issue the European Union's GDPR [General Data Protection Regulation] legislation has introduced a right to know if an automated process was used to make a decision.

"The concept of automated decision making in GDPR is that you should not be able to take a decision that affects the fundamental rights of a data subject based solely on automated decision making," explains Mr Deem.

We have a right to some some human explanation and oversight. But what if companies can't explain it? It's a grey area that will have to be tested in the courts.

So will we be happy to work alongside super-intelligent machines making beneficial decisions we might not be able to understand, or will this make us slaves to automation at the expense of our rights and freedoms as humans?

"We're quite comfortable sitting in a 1mm-thick aluminium tube hurtling through the air at 30,000 feet with only a very limited understanding of how it works, reassured by safety statistics and regulation," argues G-Research's David Stern.

"I'm confident that as long as similar oversight is in place and there is sufficient evidence of safety, we will get used to sitting in a car driven by a machine, or trusting a computer's diagnosis of our medical results," he concludes.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external