Is killing the boom the key to supersonic air travel?

- Published

Ever since Concorde's retirement many have dreamed of reintroducing supersonic travel

There have been proposals to return to faster-than-sound commercial flight ever since Concorde retired 15 years ago. But now those plans look closer to being realised.

Three US aerospace firms - Boom Supersonic, Aerion Supersonic and Spike Aerospace - are racing to be the first to slash travel times across the globe, with passenger jets that can travel faster than Mach 1 - the speed of sound (761mph or 1,225km/h at sea level).

All plan to have their aircraft in regular service by 2025.

Technologically, supersonic flight is not complex to achieve. The challenge is offering a service that passengers can afford, is less polluting, and crucially, that eliminates Concorde's window-rattling sonic booms.

The huge thunder-clap-like noise created when an aircraft breaks through the sound barrier can even cause damage to structures.

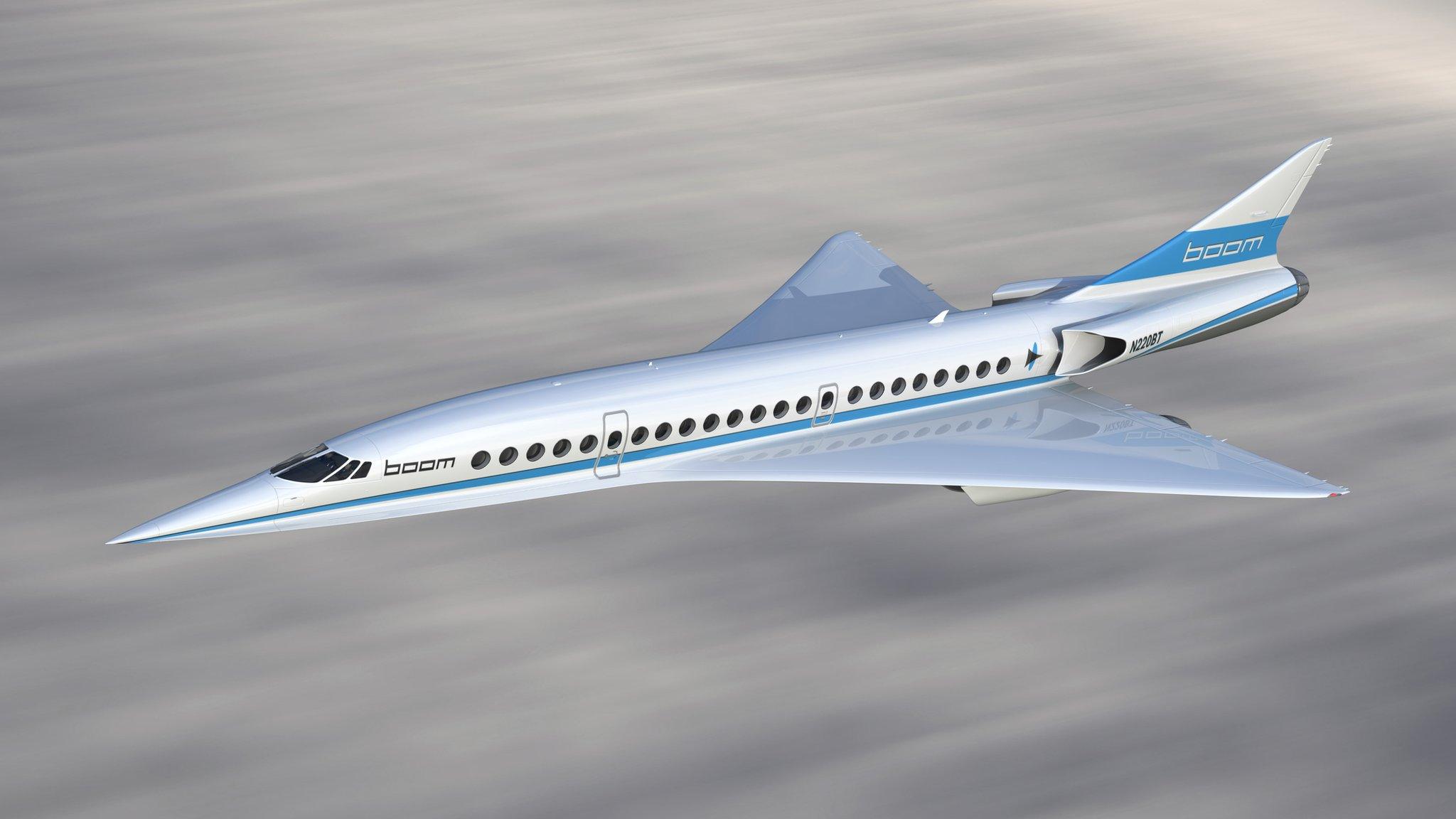

"What we're seeing now is a renaissance in entrepreneurship in aerospace," says Blake Scholl, the chief executive and founder of Boom Supersonic, which is planning to build a delta-winged airliner carrying 55 passengers at speeds up to Mach 2.2 (1,451mph; 2,335km/h).

"Concorde was really ahead of its time. It was a massive technological achievement but it was incredibly fuel-inefficient and for that reason was very expensive to operate," he says.

Boom no more?

The attitude of aviation regulators will be key in determining whether we do see a return to supersonic flight.

Earlier this year, Lockheed Martin won a $248m (£191m) contract from US space agency Nasa to build a low-boom flight demonstration aircraft. Known as the X-59 QueSST [quiet supersonic technology], it will fly at Mach 1.42 (940mph) at 55,000ft, and generate a sound about as loud as a car door closing, Nasa says.

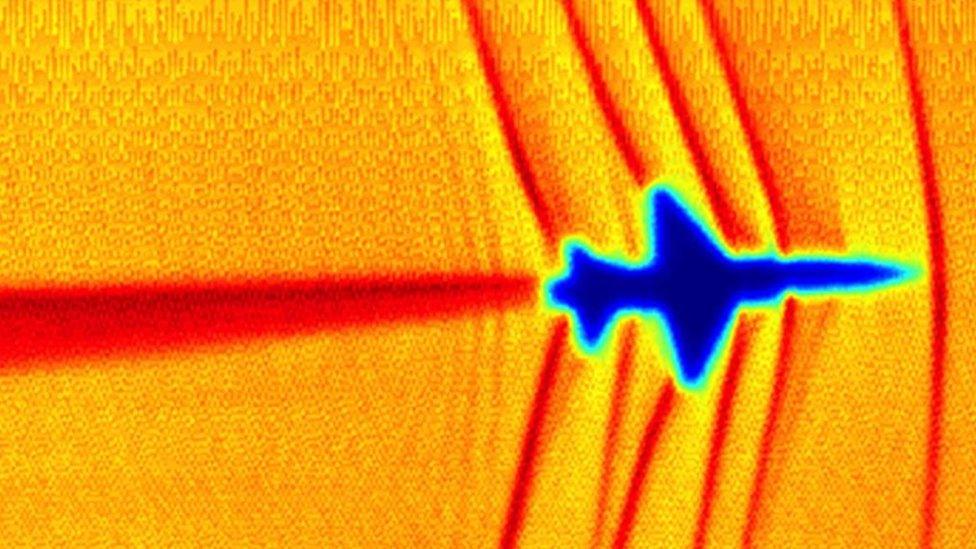

A high-speed aeroplane creates shock waves through the air that compress the faster it goes

The key to eliminating the sonic boom is in the design of an airframe. In a conventional supersonic jet, the shockwaves coalesce as they expand away from the nose and tail - leading to two distinct sonic booms.

The trick is to shape the aircraft in such a way that the shockwaves remain separate as they travel away from the aircraft. This means they reach the ground still separated, generating a quick series of soft thumps.

The aircraft should be completed by the end of 2021, and in mid-2022 Nasa will start flying it over various US cities to collect data about how people on the ground respond to the flights.

Nasa's planned Low Boom Flight Demonstration aircraft

From 2025 onwards, this will then be used by the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) and the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) in drawing up new rules regarding supersonic flight over land.

Current regulations mean civil aircraft can only go supersonic over water.

"You've got to be able to fly without a sonic boom disturbing people on the ground," says Vik Kachoria, chief executive of Spike Aerospace, whose S-512 business jet is designed to fly 12-18 passengers at Mach 1.6.

Spike says its "quiet supersonic flight technology" means it will be able to fly at supersonic speeds across land without disturbing people unduly.

Spike claims its S-512 jet can go supersonic over land without a noticeable sonic boom

Spike will not yet reveal how it will do this, but it has chosen an airframe design with wings swept back at a 55 degree angle.

Affordable supersonic?

So if the boom is being dealt with, what about the costs?

A flight on Concorde could cost four times a first-class fare. But all three firms say they aim to make supersonic travel no more expensive than today's business class fares.

The flight time from Shanghai to Los Angeles - currently about 12 hours - would shrink to a little over six hours.

"Instead of a $20,000 round-trip across the Atlantic it's more like $5,000," says Mr Scholl. "That is still expensive relative to economy - but if you can afford to fly front-cabin you can afford to get there in half the time."

Boom's planned airliner will have 55 seats

Considering four billion passengers flew in 2017, of which 12% (480 million) were in business class, that's a big potential market.

Boom is currently building a supersonic single-seater XB-1 flight test demonstrator which is due to fly next year.

Mr Scholl insists that supersonic travel does not need much new technology.

"You can do it with advanced technology that's been developed for other aircraft - carbon-fibre composites, turbofan engines, software-optimised aerodynamics."

Concorde used relatively inefficient turbojets, whereas all the proposed supersonic successors will use turbofans that are modifications of engines already in commercial use.

Boom hopes its commercial aircraft will enter service in the mid-2020s. So far two airlines have signed up - Richard Branson's Virgin Group has ordered 10; Japan Airlines, has ordered 20.

Supersonic rivals - past and present

Boeing even thinks passenger jets could even go hypersonic (beyond Mach 5) one day

Aerion Supersonic AS2 business jet - will carry up to 12 passengers at a top cruise speed of Mach 1.4. Power: three modified GE Aviation turbofans. The company promises "boomless" cruise at Mach 1.2. First commercial flights planned for 2026.

Boom Supersonic airliner - will carry 55 passengers at Mach 2.2. Power: three non-afterburning, medium-bypass turbofans with variable geometry intake and exhaust. Sonic boom will be "30 times quieter than Concorde". First commercial flights planned for 2025.

Spike Aerospace S-512 supersonic jet - will carry 12-18 passengers at Mach 1.6. Power: two turbofans. First commercial flights planned for 2025.

Aerospatiale/BAC Concorde - carried 92-128 passengers at Mach 2.04. In service 1976-2003.

Tupolev Tu-144 - carried up to 140 passengers at Mach 1.8. In service 1977-78.

Faster, firster?

Many reckon that it will be Aerion Supersonic that stands the best chance of getting its aircraft into service first.

Aerion has teamed up with Lockheed Martin to look at jointly developing its planned supersonic business jet, the AS2. Lockheed certainly has plenty of high-speed experience - with jet fighters like the F-35, F-22, and the Mach 3 SR-71 reconnaissance aircraft.

Aerion says it has already selected an existing engine for its jet - it's working with GE Aviation and will officially reveal the engine later this year.

Aerion's proposed AS2 business jet will use proven technology, says the firm

"It has over a billion hours of service flight," says Aerion's chief executive Brian Barents. "That means it can be serviced anywhere in the world."

The traditional solution for supersonic flight is a delta wing shape, but Aerion says this can cause "span-wise airflow" across the delta wing-tips, causing turbulent airflow and thus increasing drag.

It has opted for a thin wing design and horizontal stabiliser that should reduce overall drag by 20%, the company says. Nasa has already tested Aerion's planned airfoil at speeds of up to Mach 2, validating the design.

More Technology of Business

"Even though it's very fast, it's conventional in many ways - the construction techniques, the material, the systems - which de-risks the aeroplane not only for us developers but also for customers," says Mr Barents.

In an age of concerns about climate change and the environmental impact of air travel, Spike's Mr Kachoria believes that complying with current and future regulations will be key to the success or otherwise of supersonic travel, saying "it can derail the industry if you don't talk to the concerned groups".

Follow Tim Bowler on Twitter @timbowlerbbc, external

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external

- Published13 November 2017

- Published22 June 2017

- Published21 June 2017

- Published9 February 2015