The cameras that know if you're happy - or a threat

- Published

Affectiva says its algorithms can detect hidden emotions in facial expressions

Facial recognition tech is becoming more sophisticated, with some firms claiming it can even read our emotions and detect suspicious behaviour. But what implications does this have for privacy and civil liberties?

Facial recognition tech has been around for decades, but it has been progressing in leaps and bounds in recent years due to advances in computing vision and artificial intelligence (AI), tech experts say.

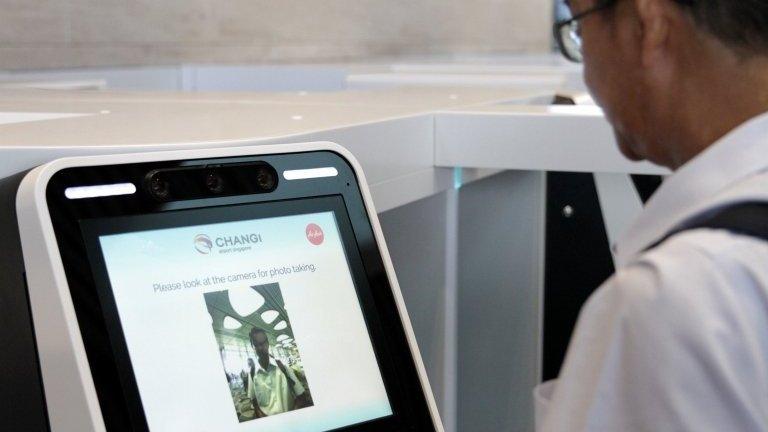

It is now being used to identify people at borders, unlock smart phones, spot criminals, and authenticate banking transactions.

But some tech firms are claiming it can also assess our emotional state.

Since the 1970s, psychologists say they have been able to detect hidden emotions by studying the "micro expressions" on someone's face in photographs and video.

Algorithms and high definition cameras can handle this process just as accurately and faster, tech firms say.

"You're already seeing it used for commercial purposes," explains Oliver Philippou, an expert in video surveillance at IHS Markit.

The iPhone X can be unlocked using facial recognition

"A supermarket might use it in the aisles, not to identify people, but to analyse who came in in terms of age and gender as well as their basic mood. It can help with targeted marketing and product placement."

Market research agency Kantar Millward Brown uses tech developed by US firm Affectiva to assess how consumers react to TV adverts.

Affectiva records video of people's faces - with their permission - then "codes" their expressions frame by frame to assess their mood.

"We interview people but we get much more nuance by also looking at their expressions. You can see exactly which part of an advert is working well and the emotional response triggered," says Graham Page, managing director of offer and innovation at Kantar Millward Brown.

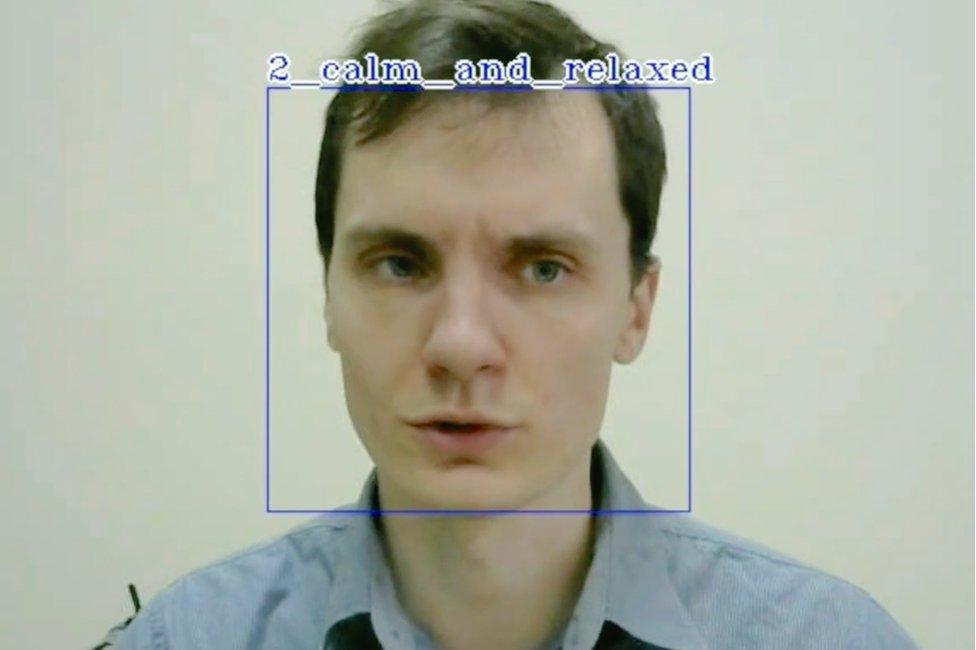

WeSee's tech is being used to assess people's emotional state during interviews

More controversially, a crop of start-ups are offering "emotion detection" for security purposes.

UK firm WeSee, for example, claims its AI tech can actually spot suspicious behaviour by reading facial cues imperceptible to the untrained eye.

Emotions, such as doubt and anger, might be hidden under the surface in contrast to the language a person is using.

WeSee says it has been working with a "high profile" organisation in law enforcement to analyse people who are being interviewed.

"Using only low-quality video footage, our technology has the ability to determine an individual's state of mind or intent through their facial expressions, posture, gestures and movement," chief executive David Fulton tells the BBC.

"In future, video cameras on a tube station platform could use our tech to detect suspicious behaviour and alert authorities to a potential terrorist threat.

Could emotion surveillance spot people likely to cause trouble at large events?

"The same could be done with crowds at events like football matches or political rallies."

But Mr Philippou is sceptical about the accuracy of emotion detection.

"When it comes simply to identifying faces, there are still decent margins of error - the best firms claim they can identify people with 90%-92% accuracy.

"When you try assess emotions, too, the margin of error gets significantly bigger."

That worries privacy campaigners who fear facial recognition tech could make wrong or biased judgements.

"While I can imagine that there are some genuinely useful use-cases, the privacy implications stemming from emotional surveillance, facial recognition and facial profiling are unprecedented," says Frederike Kaltheuner of Privacy International.

Straightforward facial recognition is controversial enough.

South Wales Police scans faces using surveillance cameras

When revellers attended BBC Radio 1's Biggest Weekend in Swansea in May, many will have been unaware that their faces were being scanned as part of a huge surveillance operation by South Wales Police.

The force had deployed its Automated Facial Recognition (AFR) system, which uses CCTV-type cameras and NEC software to identify "people of interest", comparing their faces to a database of custody images.

One man on an outstanding warrant was identified and arrested "within 10 minutes" of the tech being deployed at the music festival, says Scott Lloyd, the AFR project leader for South Wales Police.

Allow X content?

This article contains content provided by X. We ask for your permission before anything is loaded, as they may be using cookies and other technologies. You may want to read X’s cookie policy, external and privacy policy, external before accepting. To view this content choose ‘accept and continue’.

But human rights group Liberty points out that the tech has yielded large numbers of "false positive" matches at other events, such as the Champions League final in Cardiff last year.

And in July, Cardiff resident Ed Bridges - represented by Liberty - began legal action against the force, arguing that AFR violated people's privacy and lacked proper scrutiny, paving the way for a High Court battle.

But the technology is becoming more reliable, says Patrick Grother, head of biometric testing at the National Institute of Standards & Technology, a US federal agency that conducts research into facial recognition.

Chinese police recently began using sunglasses fitted with a facial recognition system

He attributes the recent technological progress to the development of "convolutional neural networks" - an advanced form of machine learning that enables a much greater degree of accuracy.

"These algorithms allow computers to analyse images at different scales and angles," he says.

"You can identify faces much more accurately, even if they are partially obscured by sunglasses or scarves. The error rate has come down ten-fold since 2014, although no algorithm is perfect."

WeSee's Mr Fulton says his tech is simply a tool to help people assess existing video footage more intelligently.

He adds that WeSee can detect emotion in faces as effectively as a human can - "with around 60%-70% accuracy".

More Technology of Business

"At the moment we can detect suspicious behaviour, but not intent, to prevent something bad from happening. But I think this is where it is going and we are already doing tests in this area."

This sounds a step closer to the "pre-crime" concept featured in the sci-fi film Minority Report, where potential criminals are arrested before their crimes have even been committed. A further concern for civil liberties organisations?

"The key question we always ask ourselves is: Who is building this technology and for what purposes?" says Privacy International's Frederike Kaltheuner. "Is it used to help us - or to judge, assess and control us?"

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external

- Published4 May 2018

- Published1 May 2018

- Published17 April 2018