How trying to stay cool could make the world even hotter

- Published

What's the best way to keep cool in a warming world?

Air conditioning systems that keep homes, offices and shops cool on hot days are rapidly gaining in popularity in a warming world. But is all the extra electricity they use going to exacerbate climate change or can design efficiencies prevent this?

The world is getting hotter, indeed 16 of the 17 warmest years on record have occurred since 2001, external, say climatologists.

It's no wonder demand for air conditioning systems is going through the roof. The energy they consume is likely to triple between now and 2050, the International Energy Agency (IEA) says.

This would mean that by 2050, the world's air conditioners would be using the current electricity capacity of the US, the European Union and Japan combined.

So scientists and tech companies are trying to make cooling systems more efficient.

Researchers at Stanford University, for example, have developed a system that uses cutting edge materials and "nano-photonics".

They've invented a wafer-thin, highly reflective material that radiates heat even in direct sunlight. The infrared, thermal energy is radiated at a wavelength that slips through the Earth's atmosphere into space, rather than being absorbed by it.

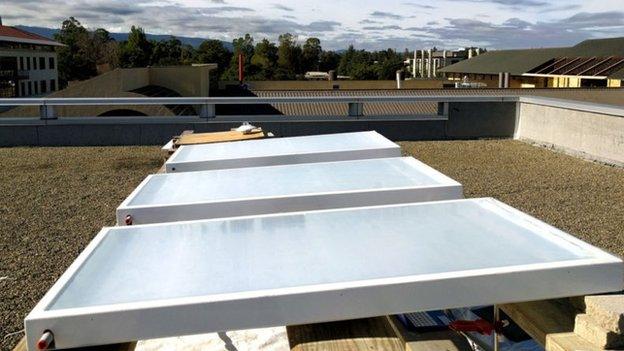

Skycool Systems' fluid cooling panels being tested on a roof

In tests, the researchers found that it could be used to cool water flowing through pipes beneath panels of the material. That water, cooled on average to a few degrees lower than the outside air temperature, could then be used to cool a building.

And this is achieved without any electricity at all.

The researchers have set up SkyCool Systems to try to commercialise the technology.

"It would be reasonable to expect that future air conditioners could be twice as good as what we're seeing now," says Danny Parker at the University of Central Florida's solar energy centre.

Mr Parker and his colleagues have spent years trying to find ways of making air conditioners and heating systems more efficient.

In 2016, for example, they found that devices cooled through the evaporation of water could be attached to conventional air conditioning units to provide a cooler feed of air.

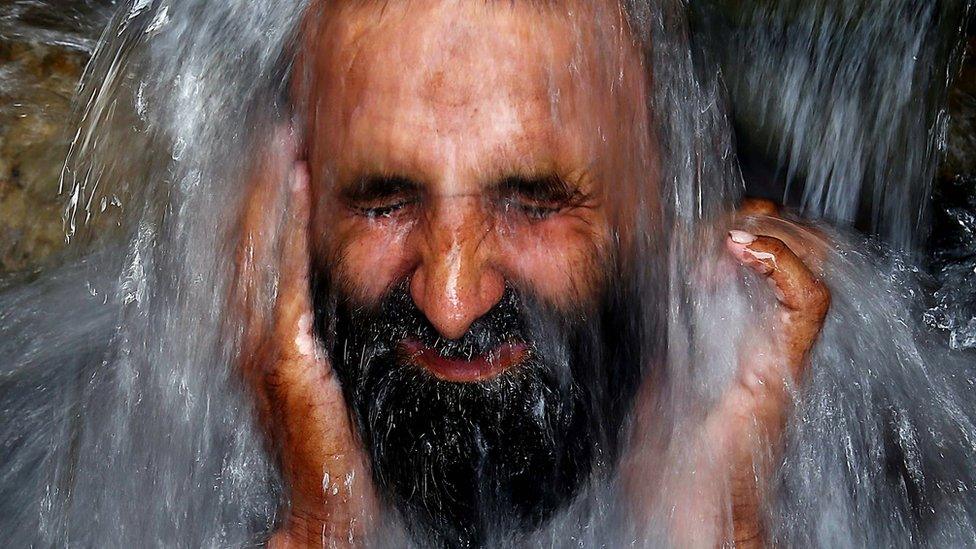

In New Delhi, India, where temperatures can approach 50C, air conditioning is essential

This meant the conventional units themselves didn't have to work so hard to pull down the temperature of incoming air. They calculated that such systems could improve cooling efficiency in many European climates by between 30% and 50%.

Tech giant Samsung has developed "wind free" technology that gently pushes cool air into a room - once the desired temperature has been reached - without the need for energy-hungry fans constantly blowing it at high velocities.

The firm says this is 32% more efficient than conventional air conditioners.

There are already many reasonably efficient air conditioners on the market - including models that make use of simple devices called inverters.

These adjust the intensity of the cooling based on sensor readings of the nearby air temperature. They can run constantly, but at low levels.

A man cools off during the recent heatwave in Karachi, Pakistan, which killed at least 60 people

Over time, that's often more efficient than a more simplistic air conditioner that runs at the same speed and has to keep switching on and off to maintain the right temperature.

"When they're not running flat-out, they're running very efficiently," says Mr Parker.

Many people in the developing world may not want to spend the extra money to get air conditioners with inverters, but if they did, that would make all the difference in terms of how the increased energy demand of new devices builds up over time, says the IEA's Brian Motherway.

"It's really about making sure people are nudged towards buying the more efficient ones," he says.

"The solution's already available on the shelves."

That may still be a hard sell in places like China, though, says Iain Staffell, an energy expert at Imperial College London.

"People want the cheapest possible unit and are not so worried about the ongoing costs of the electricity - because electricity in China is so cheap," he says.

Still, energy groups in the country launched a programme earlier this year to improve efficiency standards and labelling of products on the market.

Tado's system switches off air conditioning automatically when no-one's home

Simply managing our existing air conditioners more effectively could save a lot of energy.

For instance, Tado's "Smart AC Control" is an app-connected remote control that automatically switches air conditioners off when people leave the room. It also modifies the rate of cooling in response to online weather forecasts.

Better management like this can reduce energy consumption by 40%, claims Tado.

Of course, increased demand for air conditioning systems wouldn't matter so much if all the electricity they consumed were generated by renewable sources.

But this is unlikely, despite the rapid advance of renewables in many countries.

"We noticed that electricity demand for cooling - air conditioning in homes and buildings - was starting to grow quite quickly," says Mr Motherway.

This wasn't simply because temperatures were rising but because incomes were rising, too, in those countries most likely to be affected by global warming, he says.

China, India and Indonesia will account for half of all expected future growth in this area over next 30 years.

More Technology of Business

Yet the effects are being felt now. One Indian power company recently blamed "extensive usage of air conditioners" for high electricity demand in the north east of the country, external.

While there wasn't much growth in air conditioner sales in China in 2015 and 2016, last year saw a 45% spike, says Dinesh Kithany at research firm IHS Markit, partly caused by a very hot summer.

IHS Markit's Home Appliance Intelligence Service also estimates there were 130 million room air conditioners in use worldwide in 2016, but 160 million a year later.

While cooling innovations and a gradual switch to renewables should help mitigate the growth in demand for air conditioners, energy experts like Mr Staffell point out that, in a warming world, there'll also be less demand for central heating.

And a reduction in demand for heating could offset the rise in demand for cooling.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external