How housing has divided the young

- Published

Rising house prices have not only left fewer young people able to buy a home, they have also divided them into property "haves" and "have-nots".

Over the past 25 years only a small group of young adults have been able to get on to the property ladder - and this has been getting smaller.

A result of rapidly rising house prices, this trend has led to concerns that younger generations will never be as wealthy as their parents.

But housing inequality doesn't just exist between the young and the old.

It has also led to a divide between richer and poorer young adults.

The young homeowners

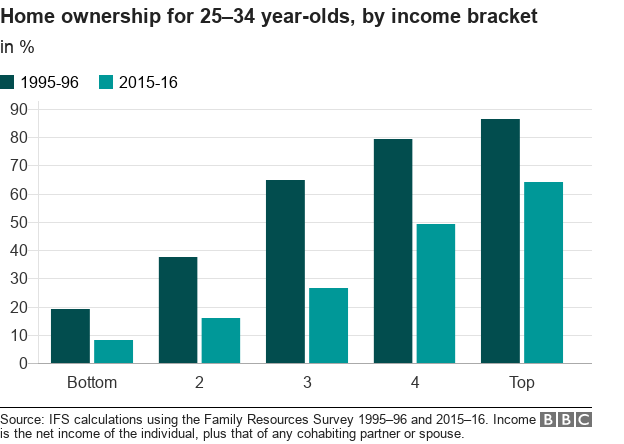

Home ownership among the young has fallen across all income groups.

Indeed, among the top fifth - those with a family income of £41,000 a year after tax - the proportion of those aged 25 to 34 who own a home has fallen from 85% 20 years ago to 65% now.

This is the same proportion as that for middle-income earners - those who would now have a family income of £22,200 to £30,600 after tax - 20 years ago.

The decline among this middle-income group has been even greater, with just 27% now homeowners.

And the proportion drops to just 8% among those on less than £15,080, who make up the bottom fifth in terms of income.

In other words, rising house prices have seen home ownership become increasingly the preserve of not just older generations but also the better-off among the young.

About 40% of young homeowners have household incomes in the top fifth of their age-group - up from 30% in the mid-1990s.

Falling behind

What has happened to explain such a huge change in a relatively short period of time?

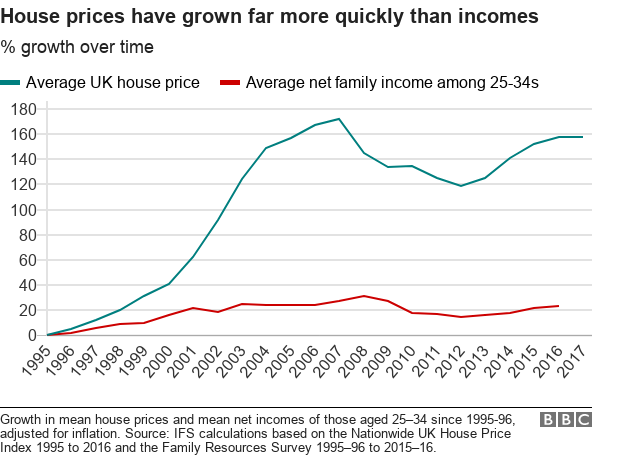

The main reason is that house prices rose rapidly during much of the 1990s and 2000s.

Accounting for inflation, house prices have risen by almost 160% since the mid-1990s while young people's incomes have grown by only 23%. This means that fewer and fewer can afford to get on the housing ladder.

This gulf can essentially explain all of the fall in the home ownership rate over the past 20 years, analysis by the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggests.

A country divided

Of course, there are a wide variety of experiences within any generation and these housing trends have not affected all young people equally.

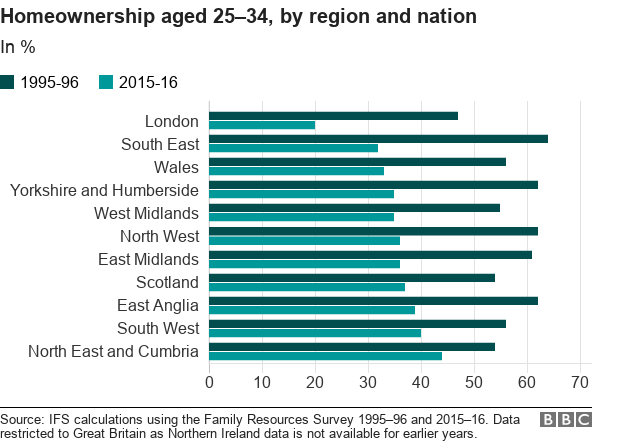

Over the past 20 years, these large falls in home ownership have been seen among young people across the country.

But some places have fared much better than others.

The biggest falls in home ownership have been in south-east England, where house prices rose especially steeply.

Twenty years ago, 64% of 25- to 34-year-olds in this area owned a home, a figure that has now halved, to just 32%.

There's a similar picture in London, where the proportion of homeowners of this age fell from 47% to 20% over the same period.

This is in contrast to smaller falls in areas where house price rises were less dramatic.

In north-east England and Cumbria, for example, the number of homeowners fell from 54% in 1995-96 to 44% in 2015-16.

Renters v owners

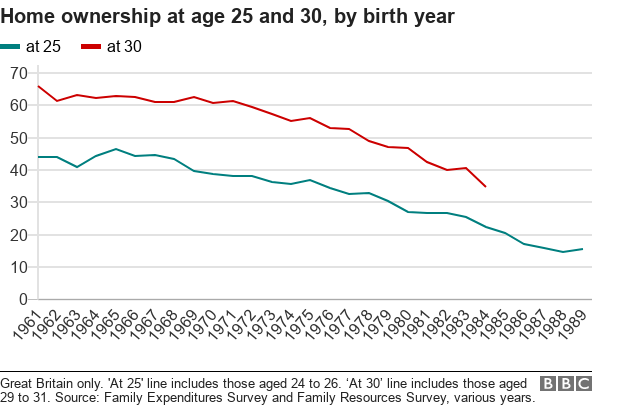

This picture of rising house prices has led to a steep decline in home ownership between the generations.

At the age of 25, 40% of people born in 1969 owned their own home, compared with 15% of those born in 1989.

And while it may be that an increasingly small band of young people own their own home, the inequalities do not end there.

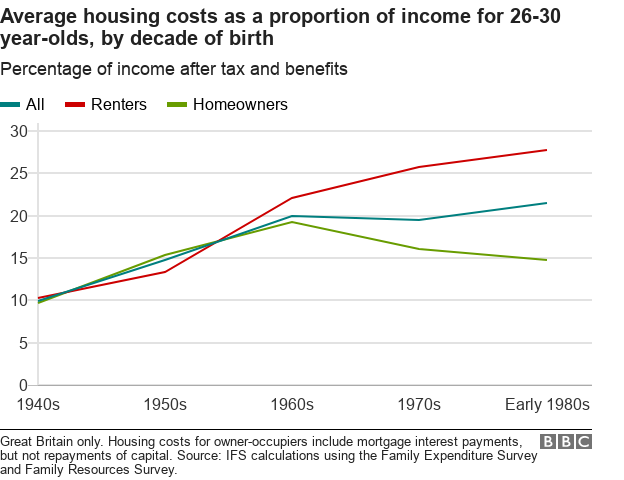

The divide between young homeowners and renters is growing over time, as those who have managed to buy a home are benefiting from historically low mortgage interest rates.

This has kept the proportion of their monthly income spent on housing each month down. When they reached their late 20s, homeowners born in the early 1980s spent 15% of their income on mortgage interest payments, compared with the 28% spent by renters of the same age.

This is tilting the playing field further against those who are unable to buy, in a way that was not true for previous generations.

In fact, because low interest rates make home ownership more attractive, they have probably helped keep house prices high.

This locks out those who can't raise a big enough deposit, while benefiting those who can.

Of course, homebuyers also have to slowly pay back the cost of the property itself as part of their overall mortgage. This means on average their total monthly payments are higher - but they will eventually own their property, unlike the renters.

Not only is this group finding home ownership out of reach but high housing costs mean that more and more young adults have less to save for the future or to spend on themselves and their families today.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Jonathan Cribb is a senior research economist, external at the Institute for Fiscal Studies, which describes itself as an independent research institute that aims to inform public debate on economics.

More details about its work can be found here, external and on Twitter, external.

Edited by Eleanor Lawrie and Duncan Walker