The UK's rapid return to city centre living

- Published

- comments

A generation ago many UK city centres were dreary and dilapidated places, with a reputation for crime. Now, they are among the most desirable areas of the country to live. What's changed?

Take a walk through the centre of cities like Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham and you will see smart new high-rise apartments, office blocks and the ever-present cranes building still more.

At street level are cafes, bars, restaurants and gyms serving their often young and affluent customers - the people who increasingly define these areas.

Only 30 years ago inner city populations that had grown rapidly in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries had dwindled - the residents leaving cramped, urban housing for more spacious suburbs and new towns.

The reversal that has taken place - especially in the north of England and the Midlands - demonstrates a dramatic urban renaissance and a shift in how people want to live.

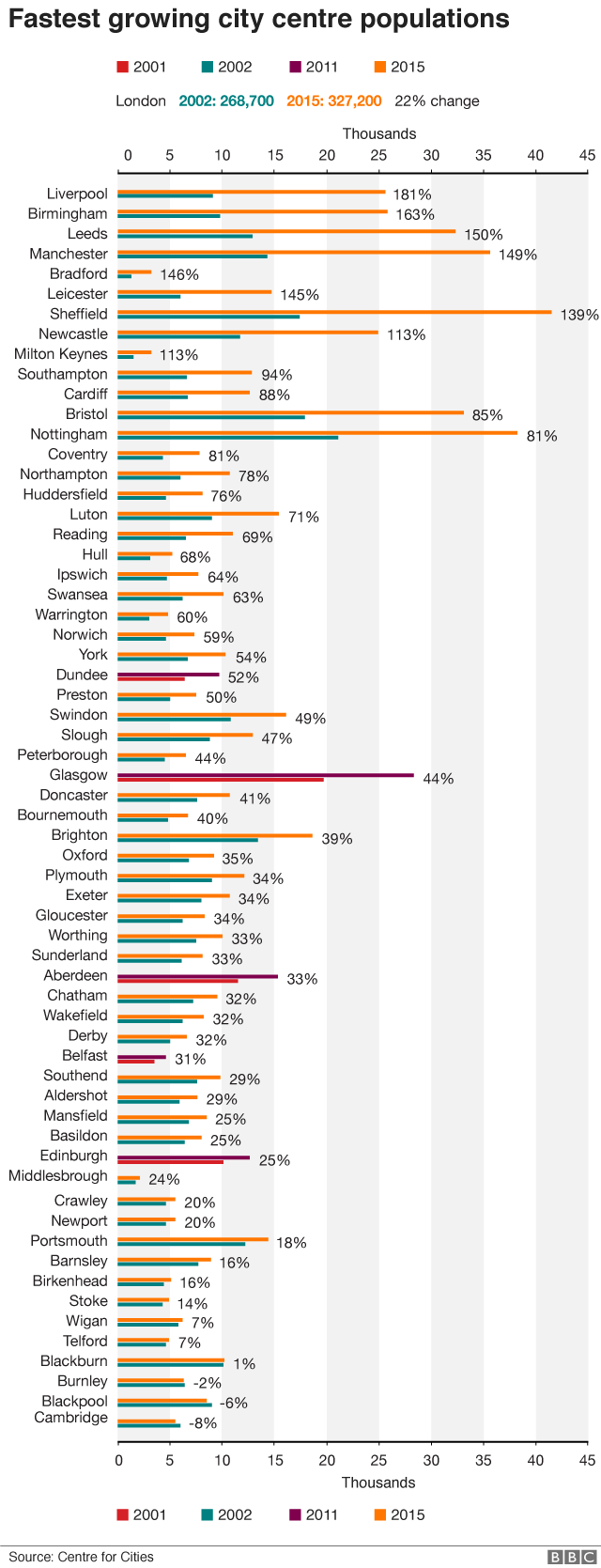

Since the start of the 21st Century the population of many town and city centres has doubled in size, while the population of the UK has increased by 10%. (Full list at bottom of story).

There is no way of saying exactly where a city centre starts or stops. So, to allow a comparison between towns and cities with 135,000 or more people, the Centre for Cities, external mapped them from the middle of their shopping and business areas as follows:

A two-mile radius from the centre of London

A 0.8-mile radius from the centre of cities with 550,000 to four million residents

A 0.6-mile radius from the centre of towns and cities of 135,000 to 550,000

Using this measure, Liverpool has the fastest growing city centre - with the population increasing by 181% (9,100 to 25,600 people) between 2002 and 2015, according to analysis of figures from the Office for National Statistics., external

Other major cities are close behind, with the population of Birmingham city centre growing 163% (9,800 to 25,800 people), Leeds increasing by 150% (12,900 to 32,300 people), Manchester 149% (14,300 to 35,600 people) and Bradford 146% (1,300 to 3,200 people).

In terms of sheer numbers, the fastest growing city centre was London, which grew from 268,700 to 327,200. However, this amounted to a relatively low 22% increase.

There was also rapid growth outside England.

Cardiff city centre's population increased by 88% (6,700 to 12,600) between 2002 and 2015.

And although detailed figures for the same period are not available for Scotland and Northern Ireland, census data suggests that Glasgow's city centre grew by 44% (19,700 to 28,300), Edinburgh's by 25% (10,100 to 12,600) and Belfast's by 31% (3,500 to 4,600) between 2001 and 2011.

Manchester enjoyed growth of 149% in its city centre population

Homes for the young

The growth in city centre living is down to young people - older generations have not returned from the suburbs in significant numbers.

Some are students, whose numbers grew with the expansion of university education.

For example, the student population in Sheffield city centre grew by more than 300% between 2001 and 2011, according to census data. By 2011 there were 18,500 students, accounting for about half the population.

Similarly, Liverpool's city centre student population grew by 208% (6,300 more people), and Leeds 151% (7,700 more people).

But the popularity of big city centres among young, single professionals is the main factor.

The number of 20 to 29-year-olds in the centre of large cities (those with 550,000 people or more) tripled in the first decade of the 21st Century, to a point where they made up half of the population. There is no reason to think that this trend has eased since the census.

Only one in five city-centre residents was married or in a civil partnership, while three-quarters were renting flats and apartments.

More than a third had a degree, compared with 27% in the suburbs and outskirts of cities.

A big pull for young professionals has been the growing number of high-skilled, high-paying office jobs available.

In big cities, more than half of the people living in the centre work in high-skilled professional occupations, reflecting the growing importance of sectors like financial and legal services to the UK economy.

Manchester, for example, had an 84% increase in city centre jobs between 1998 and 2015, while Bristol and Leeds enjoyed increases of 42% and 34% respectively.

All of these jobs have created a market for gyms, restaurants, bars and shops.

This in turn has made city centre living even more appealing - with closeness to amenities outweighing downsides like smaller living spaces, noise and pollution.

Then there's the opportunity to avoid the possibility of a long commute - 32% of city centre residents walk to work.

To some extent, governments have supported these trends, with the urban development corporations of the 1980s sparking the regeneration of city centre sites such as the Albert Dock in Liverpool and the Castlefield area of Manchester under the Conservatives.

The face of many cities continued to change in the early 2000s, as Labour invested significantly in urban regeneration programmes.

But some towns and cities have not grown at the same rate - often because they have struggled to attract high-skilled jobs and students.

Blackpool, for example, has a relatively small number of students in its centre and suffered a 13% decline in jobs between 2002 and 2015.

Elsewhere the price of land can also limit the rate of growth, as seen in London.

This has been a factor in Cambridge, where the historic city centre also limited the number of new homes built.

As such, it has seen the biggest fall in the UK, with the number of residents down 8% (6,000 to 5,500 people) between 2002 and 2015.

How much space is left?

For the most successful city centres, increased demand from both residents and businesses raises important questions about the future

Until now, places like Birmingham and Manchester have had lots of land to develop, as they recovered from their post-industrial decline.

But over the next 10 years the challenge will be meeting demand for housing without squeezing the commercial heart of the city centres.

If they are to continue attracting high-paying jobs, city centres might have to prioritise businesses.

The population of Liverpool's city centre has grown more than 180%

Some new housing might have to be further out - in the suburbs or even on green belt land.

Another solution might be to increase the density of UK city centres, which are more scarcely populated than in many other European countries.

However, given the controversy around the 30-storey St Michael's development in Manchester, or protests about tall buildings blocking views of St Paul's Cathedral in London, this may be difficult.

Another challenge is gentrification - and concerns that some people lose out because of changes taking place around their homes.

Addressing this will mean improving education and skill levels among everyone who lives there. It will also mean making more affordable housing available, to take account of different incomes.

Of course, city centres also have an important social and psychological significance beyond their economic role.

A bustling, vibrant city centre is often a source of civic pride.

A struggling city centre can become a symbol of broader social problems and decline.

This is why people care so much about the future of their city centres and want to see them thrive.

Figures from 2002-15 for England and Wales and 2001-11 for Scotland and Northern Ireland, for towns and cities with a population of 135,000 or more in the continuous built-up area

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Andrew Carter is chief executive and Paul Swinney is head of research and policy at the Centre for Cities, which describes itself as working to understand how and why economic growth and change takes place, external in the UK's cities.

Edited by Duncan Walker

- Published2 May 2018

- Published19 March 2018