Will Trump's tariffs stop Chinese espionage?

- Published

US company AMSC had its wind turbine software stolen by its one-time Chinese partner Sinovel Windpower

Dan McGahn says it was a case of attempted murder.

The victim was his business American Superconductor (AMSC), and the perpetrator was a Chinese company called Sinovel Windpower.

The two firms had been partners, but Sinovel bribed an insider to steal AMSC's key wind turbine technology.

As a result Massachusetts-based AMSC saw its sales collapse, its market value plummet by $1bn (£770m), and it had to lay off hundreds of employees.

"It was attempted corporate homicide," says Mr McGahn.

This act of industrial espionage was uncovered back in 2011, and after a seven-year legal fight, a US judge last month fined Sinovel just $1.5m, the maximum currently possible., external

While Sinovel is also continuing to pay AMSC an agreed settlement of $57.5m, the US firm is getting back just a fraction of the losses it endured.

Dan McGahn, boss of AMSC, urges US firms to be cautious when doing business in China

The case of AMSC is perhaps exactly what President Trump has in mind when he rages against Chinese industrial espionage.

At the start of last month the US government introduced tariffs on $34bn worth of Chinese exports, saying they were a result of China's "unfair trade practices", which included stealing US intellectual property.

A few days later the White House warned that the tariffs could be extended to $200bn worth of Chinese products. Then three weeks ago Trump threatened to put tariffs on all $500bn worth of annual Chinese exports to the US.

Will such a blanket tactic get Chinese firms to stop carrying out acts of industrial espionage, or should the US switch to a more targeted approach?

Firstly though, exactly how did Sinovel bribe an AMSC worker?

Global Trade

More from the BBC's series taking an international perspective on trade:

When AMSC's wind power division first went into partnership with Sinovel back in 2007, it was applauded for its global ambition and business nous at a time when countries around the world were rushing to build more and more wind farms.

AMSC knew that tying up with a Chinese firm came with risks, so it used all kinds of strategies to limit this, such as encrypting the software codes or "brains" that operated its turbines.

Yet without warning, in 2011 Sinovel said it didn't need any more shipments of the turbine technology it had been buying from AMSC.

Despite the American firm's best efforts to defend its secrets, Sinovel had bribed an AMSC employee, a Serbian national employed at its office in Austria, to hand over the key software.

The man in question - Dejan Karabasevic - had been offered money, a job, an apartment, a whole new life in China. He was found guilty by a court in Austria in 2011, external.

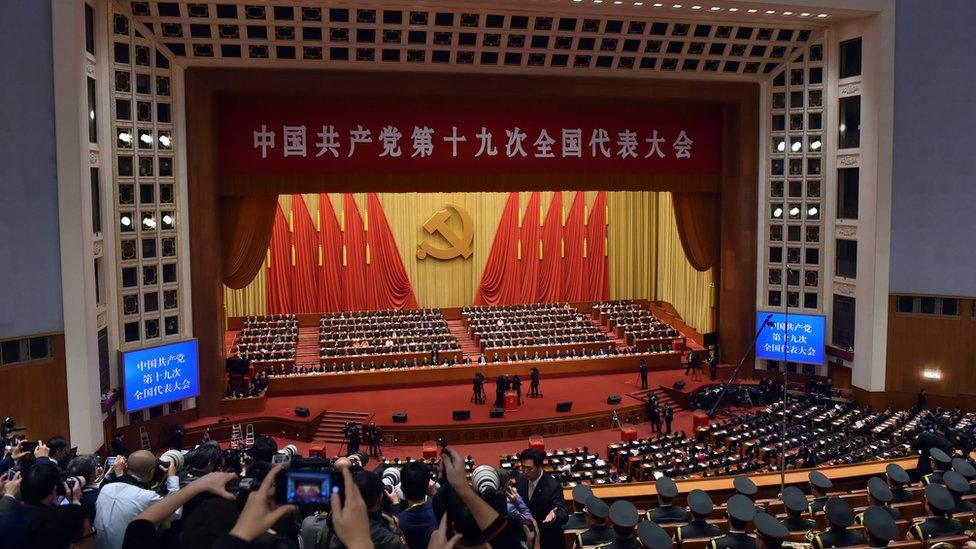

President Trump has been vocal in his attacks on Chinese business and trading practices

AMSC's case is far from unique, and US firms in sectors from metals to microchips, and telecoms and transport have complained about Chinese rivals stealing their technology. Even US biscuit stable Oreo cookies faced a Chinese copycat.

The situation is said to be so bad that the Commission on the Theft of American Intellectual Property, an independent US body including representatives from the public and private sectors, estimates that $600bn worth of US intellectual property is stolen every year, external, led by China.

Mr McGahn points out that the rules on foreign investment in China - such as the need to partner with a Chinese company - make it difficult for even the most careful overseas companies to protect their trade secrets. He says the whole system for investing in China is set up for local firms to win.

Just a few months into Mr Trump's presidency, experts convened at the White House - technical specialists, policy wonks, cabinet members and academics - to discuss how to tackle the problem.

Following a seven-month investigation a White House report accused Beijing of "state-led, market-distorting forced technology transfers".

The wind turbine sector has seen business soar over the past decade as countries around the world have rushed to build wind farms

The Chinese government always says it is doing its best to prevent infringement of intellectual property, and in 2015 it pledged to clean up those firms not playing by the rules.

But Derek Scissors, China expert at the American Enterprise Institute think tank, says China has long been a "technology leech".

In his view Beijing stands squarely behind the Chinese firms committing the thefts.

"The idea that these firms are engaging in mass industrial espionage without the blessing of the Chinese government is not the slightest bit believable," says Mr Scissors, who was one of the experts who advised the White House on the issue. "The Chinese monitor everything."

Other observers suggest that it is a more subtle process.

Mara Hvistendahl, a fellow of the New America think tank and author of a forthcoming book on industrial espionage, says that Beijing simply "looks the other way when companies steal in order to deliver [technological breakthroughs]".

An increasing amount of industrial espionage is said to be done by remote hacking of computers

Both agree though that prosecuting spies who are caught red-handed is no longer enough. It is the equivalent of arresting drug-mules, rather than the masterminds, when tackling the illegal drug trade, Ms Hvistendahl says.

Moreover, espionage is increasingly taking place in cyberspace, allowing perpetrators to remain thousands of miles beyond the reach of law enforcers. Skilful hackers may not even leave a trace of their break in.

The other obstacle to successful legal prosecutions is a lack of plaintiffs willing to face the exposure, points out Professor Mark Button, director of the Centre for Counter Fraud Studies at Portsmouth University in the UK.

"Imagine a big pharma company has a wonder drug; if that information is lost to a competitor that can have big financial implications," he says. "It can be embarrassing and it can have implications for the share price."

For that reason Prof Button speculates that the lack of high profile cases in Europe in recent years, probably disguises a hidden iceberg of incidents below the surface.

The only really effective counterespionage strategy may be better defence at the company-level, he suggests. But Prof Button has some sympathy with Mr Trump's massive tariffs approach in confronting China over their practices, in precipitating "a showdown" over the problem.

The Chinese government has always denied orchestrating industrial espionage

Derek Scissors is much more sceptical: "The solution we've come up with is completely misguided." He says blanket tariffs fail to distinguish between firms that have benefited from espionage and those that have not.

"You have to punish the guilty or you don't get a change of behaviour," he says.

Instead he'd like to see sanctions targeted against specific firms - ones that are clearly reproducing American technology that they haven't developed themselves. He believes that would be more effective than "the quick fix" chosen by the administration.

But targeting and punishing individual companies is a tough road to travel as AMSC's experience shows.

While AMSC continues to rebuild its business, Sinovel is continuing to thrive.