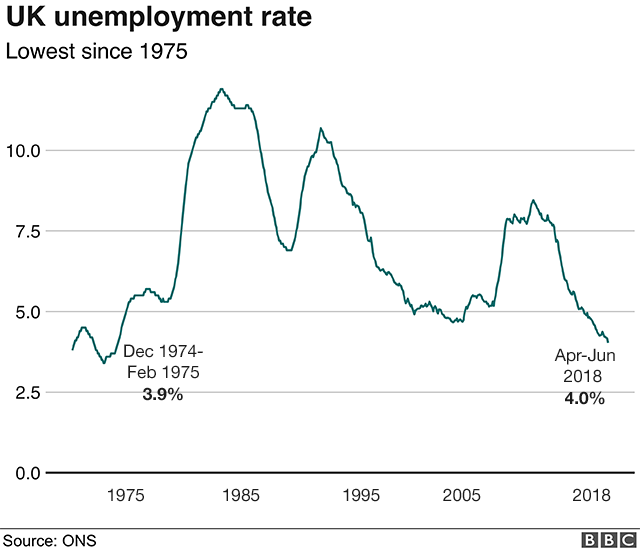

UK unemployment at lowest since 1975

- Published

UK unemployment fell by 65,000 to 1.36 million in three months to June - the lowest for more than 40 years, official figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show.

They also show a rise in productivity, but a slowdown in wage growth.

Wages, excluding bonuses, grew by 2.7% in the three months to June, compared with a year ago.

The ONS figures also showed the number of European Union nationals working in the UK fell by a record amount.

The fall was the largest annual amount since records began in 1997. It continues a trend seen since the 2016 Brexit vote.

That contrasted with a rise in the number of non-EU nationals working in the UK to 1.27 million - 74,000 more than a year earlier.

The CBI said the size of the UK workforce was shrinking at the same time as vacancies for skills and labour were growing.

Matthew Percival, CBI head of employment, said the government needed to guarantee that EU workers could continue to work even in a "no-deal" Brexit scenario.

'Economically inactive'

The unemployment rate fell to 4% in the quarter to June. That was the lowest since February 1975 and better than the figure expected by economists.

The drop came despite a smaller-than-expected 42,000 increase in the number of jobs created over the three-month period.

On productivity, the ONS also said output per hour worked was up by 1.5% - the biggest rise since late 2016.

The official figures also showed 104,000 people who were employed on "zero-hours" contracts, which do not guarantee a set number of hours per week, left such work. That left 780,000 people with those conditions as their main job.

It also said the number of people aged 16 to 64 who were not working, looking for work or available to work - what is known as "economically inactive" - increased by 77,000 from the first quarter of the year.

Analysis:

Andy Verity, economics correspondent

Here's something economists have thought for decades that they know for sure: that if unemployment keeps getting lower, wages will improve. For years, the economy's been rudely ignoring the economists' theory, with wages sagging even as the unemployment rate hits fresh lows.

But recently, reality's looked just a little more willing to conform to economic predictions. Pay rises (excluding bonuses) averaged 2.7% in the year to the end of June - higher than the official inflation number of 2.4% (but lower than the 3.4% rise in the old-style Retail Prices Index used to calculate rises in rail fares).

Judging by the unemployment rate dropping to 4.0% - its lowest since February 1975 - that coincided with an apparently super-tight labour market, meaning lots of jobs available for fewer people to fill them.

And there's a key factor making the labour market tighter: a net outflow of EU nationals working in the UK. In the second quarter of the year, the number of EU nationals was 2.28 million on the Office for National Statistics' estimates - down by 86,000. That's the biggest fall in 21 years.

Interest rates

Earlier this month, the Bank of England raised interest rates for only the second time in 10 years, as it sought to manage inflation amid signs of a strengthening UK economy.

However, Suren Thiru, head of economics at the British Chambers of Commerce, said this now looked to have been a premature move.

"Achieving sustained increases in wage growth remains a key challenge, with sluggish productivity, underemployment and the myriad of high upfront business costs weighing down on pay settlements," he said.

"As such, there remains precious little sign that wage growth is set to take off - undermining a key assumption behind the Monetary Policy Committee's recent decision to raise rates."

- Published2 August 2018

- Published30 July 2018

- Published25 July 2018