Wonga: Where have all the borrowers gone?

- Published

Katie was a student with a small maintenance loan, an occasional job, and a growing uneasiness about her finances.

She went to a series of payday lenders - including the biggest, Wonga - to help her make ends meet. Instead, the high cost of this short-term credit just made matters worse.

With little ability to repay and multiple loans, she should never have been considered for credit.

She is now seeking compensation for the loans that crippled her. In turn, such claims are crippling the finances of Wonga and other players in the payday industry.

Wonga is on the brink, saying it is considering "all options", seeking further investment as administrators stand poised if it goes under.

But what of the millions of people who have turned to Wonga and similar lenders for a quick cash fix? Are they still borrowing and, if so, from whom?

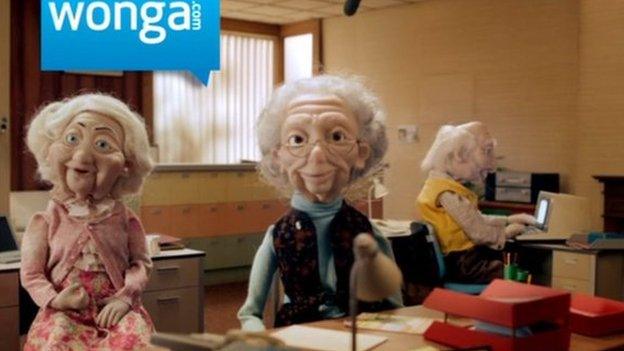

Wonga's adverts featuring puppets were controversial and eventually cut

Wonga never considered itself to be a payday lender, preferring instead to describe itself as a maverick technology company that happened to sell loans.

Its technology was groundbreaking, allowing the smartphone generation to choose how much they wanted to borrow with the slide of a thumb.

That convenience, matched with a huge advertising campaign featuring amusing puppets and upbeat voiceovers, proved a hit. At the height of its success in 2013, Wonga had a million customers.

But Mick McAteer, founder of the not-for-profit Financial Inclusion Centre, said this demand was a bubble: "They were flogging [credit] and they created demand for it."

In other words, some borrowers simply did not need to borrow from a payday lender, but were attracted towards these high-cost, short-term loans anyway.

Then, according to the current management, Wonga "lost its way", one industry insider said its history became "toxic" and regulators stepped in to cut off the credit pipeline.

Scandals, including letters from fake legal firms when chasing debts, and advancing a host of unsuitable loans, hit the Wonga brand and its popularity. Customer numbers fell from one million to 575,000.

The City regulator, the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA), ruled that from January 2015 customers must face stricter affordability checks, set a price cap that slashed the typical interest rate, and said nobody should ever have to repay more than twice the amount borrowed. They also required every lender to go through an authorisation process.

Mr McAteer said the effect was to restore a healthy balance in the credit market. "The emphasis now is that the customer looks for credit, rather than the other way around," he said.

Wonga adverts showed the type of people it hoped to attract as customers

Wonga's management changed, it made a loss, and it attempted a reinvention. Out went the puppets, and in came TV adverts featuring "hard-working dinner ladies and mums".

In 2015, its typical customer was male and aged between 20 and 35, but it suggested there was a broader market.

It published an unusual estimate, claiming that its research suggested around 13 million people in the UK were "cash and credit-constrained" and under-served by mainstream financial services.

Some people were starting to get a bit of a pay rise after years of squeezed wages, and employment levels continued to improve - allowing some to avoid any need to turn to short-term loans. Some managed to save enough for the rainy day fund.

Credit card transfer deals were becoming increasingly attractive, allowing people to park debt for months or even years. Low interest rates meant borrowing from the mainstream financial institutions on the High Street was comparatively cheap. Many still fell into unauthorised overdrafts.

Following the FCA crackdown, many payday lenders decided to leave the market and some collapsed. Those that remained shifted the focus of their products. Wonga moved to longer term, more flexible loans. According to its latest figures, customer numbers dropped to 220,000 by September 2017.

But what about those "credit-constrained customers" - people who may have defaulted on loans, overdrafts and credit cards in the past, or have moved into the country with no credit history and so struggle to secure more credit from banks or building societies?

Regulators have laid the pitch for not-for-profit credit unions to deliver to this group of people - but they do not have the capacity to serve them all.

There is little evidence of a rise in the use of illegal loan sharks, although the FCA said some families desperate for money are being targeted by money lenders handing out cards at the school gates and outside food banks.

For the majority, as hinted by the FCA's own research, loans are being provided closer to home. The regulator's Financial Lives, external survey revealed that 3.6 million people (7% of UK adults) are borrowing from friends and family, or had done so in the previous 12 months. The highest proportion were aged 25 to 34, and more of them were women than men.

That is more than the 3.1 million (6% of UK adults) who took out high-cost credit.

'A bit rich'

Some people are going still going to short-term lenders, some with their family acting as guarantors. Debt charities say payday lenders remain an option, but are usually not the best option.

All the while, they cannot shake the shadow of the past. They are facing a swarm of legacy complaints that cost time and money. Wonga was forced to seek a bailout from its backers this month amid a surge in claims.

One senior industry source said that claims management companies had become a major problem for payday lenders after they shifted their focus from PPI.

Some say many of these claims are vexatious, but lead to a complaint-handling fee anyway. Others feel a sense of injustice that the regulator allowed retrospective claims when loans had been transparent.

Nick Baxter, from trade body the Professional Financial Claims Association, said it was "a bit rich" for payday lenders to blame claims companies for being "the check and balance in the system".

One thing is for sure: rich is not a word many payday loan customers would use then - or now.

- Published26 August 2018

- Published28 September 2017

- Published27 August 2018