Why Asia turned to China during the global financial crisis

- Published

Singaporean Declan Ee was working for Lehman Brothers in London when the bank collapsed

For many young people in Asia, going to the West to study and work is the stuff dreams are made of.

But that dream turned into a nightmare for Declan Ee when he became an unwitting victim of the financial crisis 10 years ago.

He was working for Lehman Brothers in the sub-prime mortgage division in London as a junior banker at the time, and was on a career path to success. Or so the young Singaporean thought.

"I never felt safe after the global financial crisis," he tells me. "I had really bought into the whole culture of the industry at the time."

Declan was one of thousands who lost their jobs during the Lehman Brothers collapse, an event which many mark as the start of the crisis.

Overnight, credit dried up. Jobs disappeared. Banks lost billions of dollars.

The developed world fell into economic disarray.

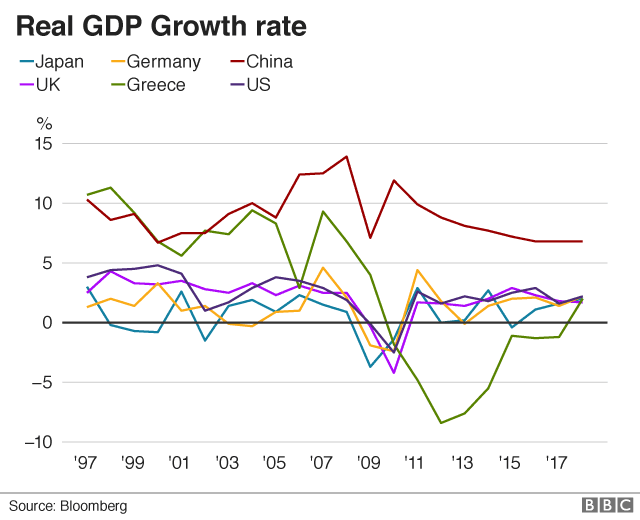

As the chart below shows the US, UK and Japan all fell into recession. It has taken a decade to recover from that, and many economists would argue that we are yet to see a real recovery.

Asia hit too

Ultimately though, this was effectively a crisis of global confidence in the ability of banks to survive. Asia's financial sector wasn't spared, although it wasn't hit nearly as badly as the West.

Ten years ago, many of Asia's banks were facing job losses, wage freezes and cost cutting measures.

DBS - South East Asia's largest bank - was also affected. The bank had to write off millions of dollars worth of loans and investments because of its exposure to the crisis.

Terence Yong Yew Tiek was on the frontline for the bank at the time and remembers how tough it was.

But he says DBS - like so many other businesses in the region - was only momentarily affected, and recovered quickly because of the inherent strength in Asia's economies - and China.

"Fundamentally, there was broad-based growth across Asia," he says. "Whether that was in the auto sector, airlines, consumer goods, commodities, services - all of these things were actually growing because of middle-income growth in Asia. China was also increasingly a factor, and that drove demand across borders within Asia."

Who was to blame for the financial crisis?

Don't count on just one market

The global financial crisis meant Asian companies had to change tactics too.

Singapore-based plastic parts maker Sunningdale Tech saw its automotive products orders from North American clients fall to zero during the crisis.

The company's chief executive, Khoo Boo Hor, has vivid memories of the time.

The firm had to cut salaries, shorten the working week and reduce executive pay just to survive. But the crisis taught Sunningdale a valuable lesson: you can't count on just one market.

"You have to assume that if a crisis has happened in one region, it may happen in another region," he told me. "So what we do today is we build a model - we don't depend on one country, one region, one product or one customer."

Asia in, West out

That growth in Asia and China coincided, some say, with an increasing disdain and lack of trust among many in the region of the West's financial practices.

Sunningdale Tech's Khoo Boo Hor has learnt not to depend on just one country or region

Investment manager Hugh Young is a bit of a crisis connoisseur - he has lived through two of them. He says the global financial crisis changed the way Asia viewed the West.

"It would be the start... of Asia looking away from the West," he told me.

"That's been a steady phenomenon, and if anything the global financial crisis accelerated that. It probably also accelerated the rise of China - which was going to happen anyhow - but now we see China playing on the global stage as big a role - arguably a bigger role - than even the US."

Chinese stimulus

China was a big factor in why Asia managed to escape the global financial crisis relatively unscathed.

But that's not to say China wasn't affected by the crisis. On the contrary, as Yu Yongding, a former member of the Monetary Policy Committee of the People's Bank of China, explains the turning point of China's growth happened in September 2008,, external after the Lehman Brothers' bankruptcy.

"Banking's Black Monday" in September 2008 had ramifications around the world

A closer look at his numbers will illustrate exactly what he means.

In 2007, China's GDP growth rate was 13%.

In 2008, after the Lehman Brothers fiasco, GDP fell to 9% in the third quarter and 6.8% in the fourth quarter.

In the first quarter of 2009, China's growth rate fell further to 6.1%.

The Chinese government "took action swiftly" as Professor Yu says, and introduced a massive stimulus package which didn't just help to stabilise and revive China's economy - it became the lifeline for the rest of Asia.

But there are concerns that China's economy is now mired in a mountain of debt, and as the International Monetary Fund pointed out in its outlook for the world economy earlier this year, the large and opaque nature of the financial system in China poses a risk to stability, external.

Another crisis?

The last 10 years have seen strong growth in Asia and China and that's helped this region weather the storm during the global financial crisis.

For better or for worse, it shifted Asia away from a heavy reliance on the West.

But now with Asia's biggest economy - China - slowing down, the big fear is that another crisis could be brewing.

No-one's quite sure where it would start this time - and how badly we could all be affected.