Brexit questions: Warehouse edition

- Published

Where will all the stuff go?

Because it is hard to see how Brexit doesn't (at some point) involve British businesses wanting or needing to keep more stuff closer to home. By stuff, I mean parts, raw materials or inventories of finished products.

There is a short term and, to a lesser extent, a longer term question here. Given uncertainty about what happens next March when we leave the EU, many businesses may want to have extra supplies on hand in case a disorderly exit leads to disruption at our borders. One estimate put this stockpiling of imports at about £40 billion, external.

But longer-term, more bureaucracy, paperwork, checks or delays on imports could also induce companies to keep more (and potentially manufacture more) in the UK. This would be a much smaller figure - but could vary depending on what exactly the new arrangements are and how confident companies feel that they will to work.

'Under-warehoused'

And the trouble is, the UK doesn't have much space - specifically warehousing space.

We are, according to property company Savills, external, an "under-warehoused country". Our warehousing stock works out to about 7.6 square foot of space per head compared to the US at 39 square foot per head.

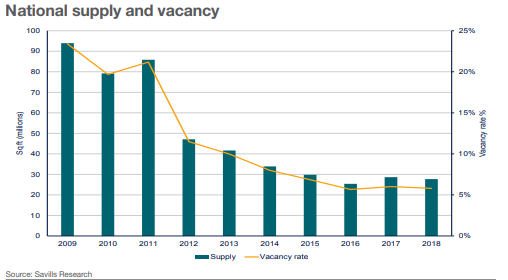

It is also a market that has been squeezed both on the supply and the demand side. Speculative development - or building a warehouse without a tenant already signed up to take it - fell sharply after the financial crisis started in 2007. Readily-available funding to speculatively build large warehouses and logistics facilities has never really recovered.

Meanwhile, the rapacious growth of e-commerce has gobbled up space in recent years. Amazon dominated the market in terms of demand between about 2014 and 2016, according to one expert, and retailing still accounts for about two-thirds of take-up of space.

The result is this: a sharp fall in the vacancy rate for warehouses of over 100,000 square feet.

The national vacancy rate is about 6%, and is as low as 3% in some areas of London and the South East. One industry rule of thumb holds that a vacancy rate of under 10% is a catalyst for rising rents.

(So this is one example of a sector that is probably benefitting from uncertainty around Brexit. Indeed, there are signs that speculative development is starting to pick up as some scent an opportunity.)

Cold storage hotting up

Still, some car manufacturers have told Newsnight that there isn't enough warehousing space near their factories to be fully ready for a no-deal Brexit. And perhaps that isn't surprising, given the scale involved. Honda has estimated that holding the required nine days of supply would require a warehouse the size of 42 football pitches, according to the FT, external.

Other sectors may also find themselves tight. Specialist types of space - like cold storage for frozen foods - tend to be in shorter supply. NewCold, a company focused on frozen supply chain logistics, says it has started to receive Brexit-related demands for space, including from food companies wanting to increase stocks of food in the first half of next year. It has left a 'Brexit buffer' in its recently-expanded Wakefield facility and is planning to build another site further south once an anchor tenant is secured.

Greater trade friction, delays at ports and airports, a rethink of international supply chains. Many of the potential knock-on effects from Brexit have something in common: they require space. And the UK may find itself wanting more of it in a hurry.

- Published24 September 2018

- Published24 September 2018