Brexit: What happens next?

- Published

Theresa May: "I will not overturn result of the referendum"

Theresa May has warned that the Brexit negotiations are at an impasse and there will be no progress until the EU treats her proposals seriously.

She has accused EU leaders of showing the UK a lack of respect after they rebuffed her Chequers plan at the Salzburg summit without, she said, any alternative or explanation.

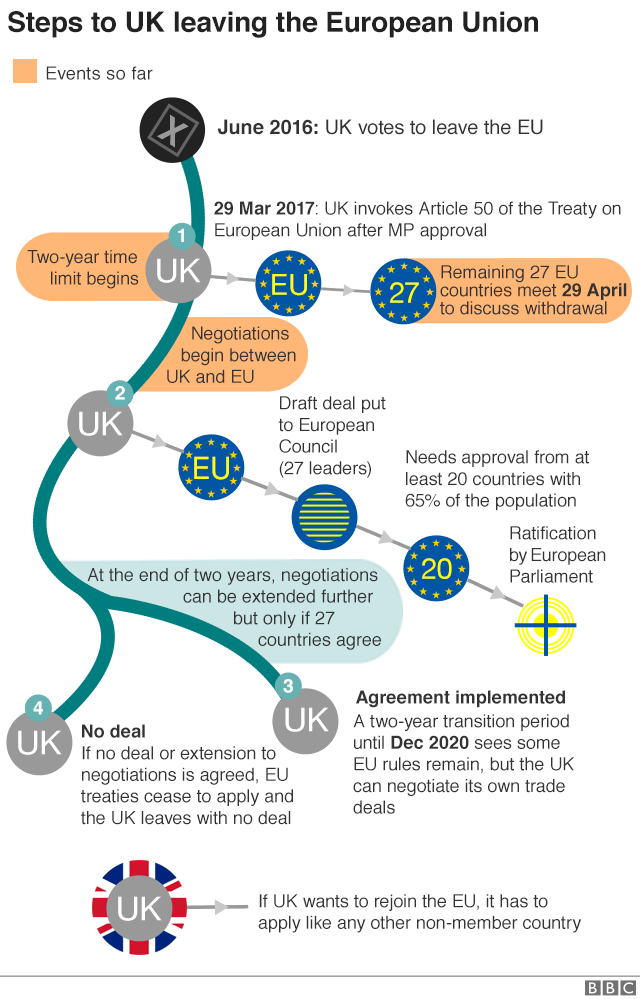

With the clock counting down to the UK's scheduled exit on 29 March 2019, where does this latest row leave the chances of a deal and what could happen next in the Brexit process?

Beyond Salzburg

Mrs May has said the two sides remain "a long way" apart on the crucial issues of how the UK will trade with the EU after Brexit and the future of the border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland.

She reiterated again her belief that her Chequers blueprint, external was the only way of properly implementing Brexit and also ensuring a "deep and special partnership" with the EU in the future.

The PM has also rejected the two options put on the table by the EU - a Norway-style association agreement and a much looser relationship based on Canada's trade deal with the EU.

For its part, the EU has said the Chequers plan is unworkable as it fragments the single market.

The next few weeks will be crucial if these differences are to be resolved and the two sides are to fulfil their shared aim of an orderly Brexit and an outline agreement on trade, security and other issues.

The Conservative conference (30 September)

Boris Johnson quit over the Chequers plan and has since criticised it relentlessly

Mrs May has suffered plenty of Brexit setbacks in the past and soldiered but many of her own MPs don't think she is going about the process of leaving the EU the right way.

The number of Tories who say they won't vote for the Chequers plan seems to be growing by the day and, remember, any deal she negotiates with the EU has to get through Parliament.

There is enormous pressure from the Brexiteer-wing of the party for her to rip up Chequers and throw her weight behind an enhanced version of Canada's 2016 deal with the EU.

The so-called Canada Plus Plus option, which removes most customs duties on goods but without paying for access to the single market, is backed by Boris Johnson, David Davis and Jacob Rees-Mogg, among others, who believe the UK Parliament will vote for it.

Many Conservative Remainers, like former minister Justine Greening, have also lost faith in Chequers and think there should be a referendum (more of that later) while some Tories think the UK may well end up in a temporary European Economic Area-style arrangement, sometimes called the Norway option.

This would mean accepting the free movement of people and the indirect recognition of European Court of Justice rulings - but would allow businesses access to the EU single market, with some strings attached.

Amid speculation about further cabinet resignations if she persists with Chequers, calls for the PM to think again are likely to reach a crescendo at the Conservative Party conference in Birmingham.

If the PM does not shift on the substance of her Chequers plan, expect much frenzied talk of leadership challenges.

Decision time in Europe (November)

Will the French president give Brexit the thumbs-up?

Salzburg may have caused a dust-up but it hasn't changed the underlying reality that both sides want as amicable a divorce as possible.

Some Tory MPs favour a clean break with the EU, which would see the UK fall back on its membership of the World Trade Organization, the global body governing international trade, but they are in a minority.

Both sides are ramping up talk of no-deal contingency planning.

But they also know that such an outcome would be seen as a political failure and a disaster for business - particularly as the 21-month transition period planned after Brexit day would be scrapped.

A summit on 18-19 October of EU leaders was, for a long time, pencilled in as the moment that the two sides would have to look each other in the eye and reach a deal.

However, this is not now seen as feasible and the focus is on a special one-off summit that has been arranged for mid-November.

An agreement then, the thinking goes, would still allow enough time for the UK and European Parliaments and a supermajority of European states - that's 20 out of 27 - to ratify any deal before the 29 March deadline.

So, the clock is ticking but the EU is renowned for finalising deals at the 11th hour and it wouldn't be the first time the talks have seemed on the brink of collapse only for a deal to be pulled out of the fire.

The Parliamentary showdown (December-February)

If she brings a deal back from Brussels, Theresa May has another big hurdle to negotiate. She must persuade Parliament to back it, in a vote likely before the end of the year or in early 2019.

Tory Brexiteers opposed to Chequers have suggested up to 80 MPs would be prepared to vote against it.

Although we don't know what the final deal will look like and the size of any rebellion would, in all likelihood, be much smaller, even a dozen Conservatives defying the leadership would risk defeat for the PM, with her non-existent Commons majority.

The opposition parties are unlikely to come to the PM's aid, with Labour saying any deal is unlikely to pass its six tests guaranteeing workers' rights and all the "benefits" of the single market and customs union.

The Labour leadership is hoping to inflict a defeat as a way of triggering a general election.

Brexit Day, another referendum or general election? (2019)

Some Leave campaigners are bracing themselves for another referendum

It is written into law that the UK will be leaving at 23:00 GMT on 29 March 2019, two years to the day after the government notified the EU of its intention to quit, by triggering Article 50 of the EU's Lisbon Treaty.

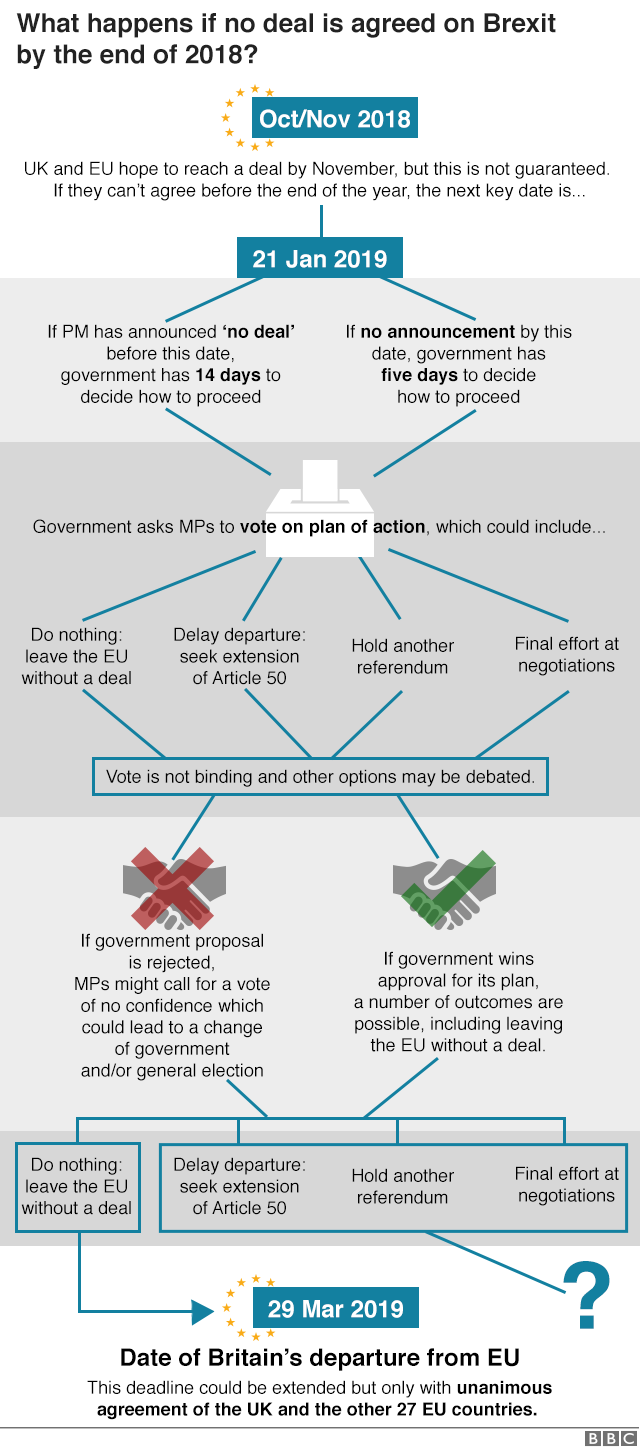

But if there is no deal or Parliament rejects the deal, we are in uncharted territory and it is impossible to say with any certainty what will happen next.

Mrs May has insisted the 2016 referendum result will not be overturned but if Parliament cannot agree on what kind of Brexit it wants, a fresh public vote might yet end up being the only way to break the deadlock.

But how could this happen?

Should Mrs May lose a vote on her deal, she could conceivably resign and her successor may use his or her new mandate to seek Commons approval for a vote on another referendum.

Alternatively, MPs who back a so-called People's Vote - which include the Liberal Democrats, the SNP, Plaid Cymru as well as a growing number of Labour MPs - could seek to table a backbench amendment to the legislation that has been promised to implement the UK's withdrawal.

With most Tories, so far, publicly opposed to a referendum, any vote is likely to be extremely tight.

Either way, Parliament would then need to pass enabling legislation, similar to the 2015 European Referendum Act, setting out the date of the poll, the question and the franchise, as well as other details.

As it stands, if no deal has been agreed by 21 January 2019, ministers will be required to make a statement to Parliament about the next steps. This could trigger the mother of parliamentary battles over Brexit.

Some European leaders believe Brexit can be halted but unless Mrs May or her successor and the other 27 nations agree to extend the two-year Article 50 process beyond 29 March, this cannot legally happen.

Critics say there won't be enough time while there is also another stumbling block in that those who back a vote do not all agree on what question should be asked on the ballot paper.

While the People's Vote campaign wants the option to remain, the Labour leadership has said it should be on the terms of the deal - in other words between leaving with Mrs May's deal or no deal.

What Labour really wants is a general election so it can take over the negotiations. It is only after 29 March that discussions about future co-operation - including a trade deal - will really begin in earnest.