How does the world tip? In some places, it’s actually offensive!

- Published

Tipping has become a political issue in the United Kingdom

It is a dilemma most experienced travellers will have encountered at one time or another - whether to give a tip or not? And, if so, how much?

It is a minefield where offence can easily - if inadvertently - be given, either by tipping in the first place, or by giving too large or small a gratuity.

The topic has been taxing both main political parties in the UK this week, as they have chewed over laws forbidding bar and restaurants from keeping tips from staff.

Not every country in the world takes the matter as seriously as the British, who are believed to have invented the custom in the 17th Century - originally as an aristocratic practice of giving small gifts to the so-called "inferior classes".

Tipping, nonetheless, is a habit widely indulged around the world, although it is tangled up in a nation's culture and values.

United States

In countries like the United States, tips form a substantial part of workers' wages

A common joke amongst Americans is that only a filing tax return is more confusing than tipping.

Gratuities were imported into the country in the 19th Century, when wealthy Americans began travelling to Europe. The custom was originally frowned upon and critics considered it anti-democratic and accused tippers of creating a class of workers who “begged for favours”.

Fast forward to the 21st Century and you will still find Americans debating the pros and cons. But tipping is now completely ingrained in the national psyche: economist Ofer Azar estimated in 2007 that the restaurant business alone saw $42bn (£32bn) given to service workers. In the US, the tips are an important complement to wages.

China

Tipping was frowned upon in China and it's still not widespread

Like many Asian countries, China has a largely a no-tipping culture - for decades it was actually prohibited and considered a bribe. To this day, it remains relatively uncommon.

At restaurants frequented by locals, customers do not leave gratuities.

Exceptions are restaurants mainly catering to foreign visitors, and hotels with a similarly international clientele (even then it's only acceptable to tip baggage handlers).

Another exception is to leave gratuities for tour guides and tour bus drivers.

Japan

Tipping a waiter can cause offence in Japan

Japan’s intricate etiquette system encompasses gratuities. It is socially acceptable on occasions such as weddings, funerals, and special events, but on more common situations, it can actually make the receiver feel belittled, if not insulted.

The philosophy is that good service should be expected in the first place. Even on occasions where tips are expected, it follows a protocol that includes handing the money in special envelopes as a sign of gratitude and respect.

Hotel personnel, who are almost universally courteous and prompt, are trained to politely refuse tips.

France

France was one of the first countries to adopt a service charge in restaurants

In 1955, France passed a law requiring restaurants to add a service charge to bills - a practice that then became common around Europe and other parts of the world - as a way to improve wages for waiters and make them less reliant on tips.

However, tipping remained customary, despite surveys showing that younger generations of French tend to be non-tippers: in 2014, 15% of French customers said they would “never tip”, a number twice as big as in the previous year.

South Africa

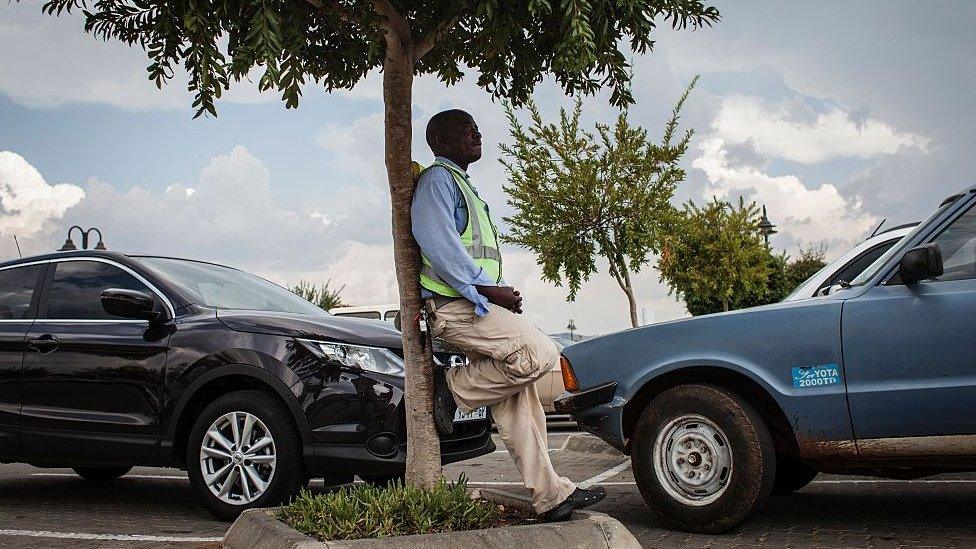

The Rainbow Nation features here for a specific service not usually covered in many other countries: car guarding.

It’s an informal industry that has grown in proportion to South Africa’s unemployment rate - now 25% - and basically consists of individuals who help motorists by finding parking spots for drivers and watching their vehicles - according to official statistics, almost 140 vehicles were stolen every day in the country last year.

Paying less than $1 for the service is not the problem here: the debate in South Africa is that the process is almost completely unregulated and has no guarantee that either party will keep their part of the bargain.

Car guards have caused a debate in South Africa

Switzerland

People in Switzerland are often said to financially round up bills and to leave gratuities to hotel staff and workers such as hairdressers. However, the country has one of the highest minimum wages in the world: waiters, for instance, earn over $4,000 a month. Thus, they are not as dependent on tips as their American counterparts.

India

Many restaurants in India levy service charges on the bill, so it is considered OK not to leave a tip. Otherwise, the etiquette is to leave 15%-20%. It is not uncommon to find restaurants which display signs against tips. A 2015 survey revealed that Indians were amongst the highest tippers in Asia, behind only Bangladesh and Thailand.

Singapore

Singapore's authorities are not fond of tipping

Although small handouts will not cause offence at hotels, restaurants and taxis, gratuities can be a thorny issue in Singapore. The government website states that “tipping is not a way of life” on the island.

Egypt

Egypt's reliance on the informal sector intensified the "baksheesh" culture

Tipping is deeply ingrained in Egypt and a gratuity is known as baksheesh. Well-off Egyptians regularly tip all kind of service workers, from waiters to petrol pump attendants. The handouts are welcome in an economy with unemployment over 10% and in which the informal sector contributes to almost 40% of GDP.

Iran

The complex taroof ritual does not apply to tipping in Iran

Visitors to Iran might come across the taroof ritual - the practice of deference in which payment is initially refused as a matter of politeness - it can happen even in cab rides, where the driver will initially refuse to accept payment.

But it won't happen with a tip: gratuities for services are part of daily life.

Russia

During the Soviet Era, tipping was a no-no in Russia - it was considered a means of belittling the working class.

But Russians do have a word for it - chayeviye ("for the tea").

Tipping made a comeback in the 2000s. Still, older people may find it offensive.

Argentina

Tipping a waiter after a good steak-Malbec combination won't lead to trouble in Argentina, although it is actually illegal under a 2004 labour law for the catering and hotel industries.

Still, the handouts take place and can correspond to up to 40% of an Argentine waiter's income.