Should race count in university admissions?

- Published

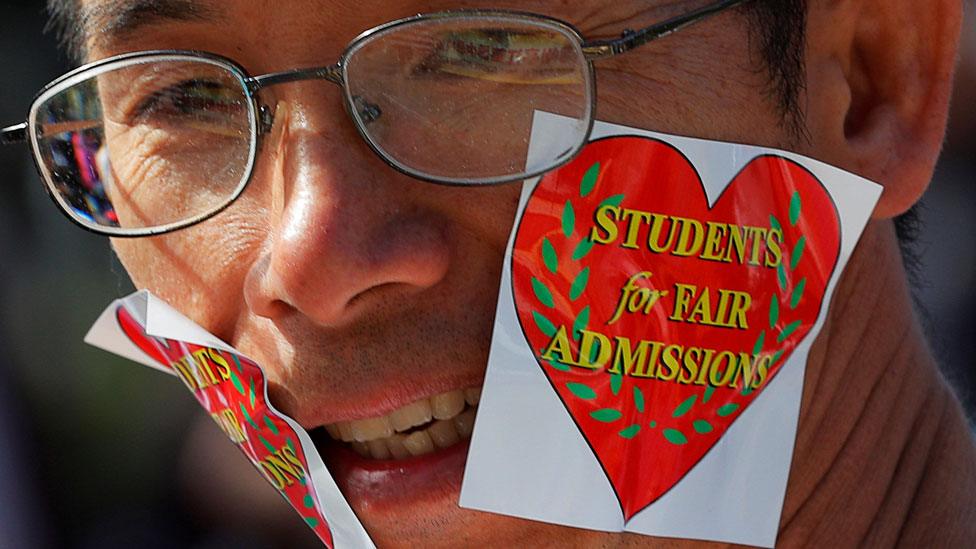

Harvard is at the centre of competing visions of what is meant by "fair" admissions

Harvard University this year turned down more than 95% of those who applied.

But what is a "fair" system for deciding who should be rejected and who should be the lucky few to get a place?

What should the successful 5% look like?

Should it just be those with the highest academic credentials? Or would it be fairer to ensure a more diverse ethnic and social mix?

The admissions policy of the flagship US university is facing a legal challenge, which began this week in Boston, with accusations of racial bias against Asian-Americans.

And it's a dispute that will be watched carefully by many other over-subscribed universities around the world.

'Racial balancing'

In the UK, top universities such as Oxford have been criticised for recruiting too few ethnic minority students.

But the legal challenge against Harvard shows how this argument can become more complex - because a majority of students in this autumn's intake are from ethnic minorities.

The accusation is that Harvard is limiting places for Asian-Americans to allow entry for other minorities

About 52% of new undergraduates are from ethnic minorities, with the biggest number being Asian Americans:

15% black

12% Hispanic

2% Native American or Native Hawaiian

23% Asian American

'Race neutral'

But the complainants say if entry was decided on grades alone, the proportion of Asian-American students would be even higher - and the admissions system makes it easier for black, Hispanic and white students to get a place.

The court case has been seen as reflecting a wider push-back against "affirmative action"

Asian-Americans are about 6% of the US population, so they are the most over-represented ethnic group in Harvard. But the complainants say there is an informal system of "racial balancing" to cap any further increase in their numbers.

They claim that more subjective parts of the entry process, such as assessing an applicant's personality, are used to mark down Asian-Americans.

Under the banner of Students for Fair Admissions, they are calling for race to be removed as a factor in admissions, saying that the ethnicity of applicants should not "either help or harm" chances of entry.

'Only one factor'

Harvard strongly denies any accusation of unfairness.

It says that race is "one factor among many" and the proportion of places gained by Asian-American students has risen by more than a quarter since 2010.

The university has defended the impartiality of what it calls a "race conscious" system, as it sifts through 42,000 applications to make about 2,000 offers.

An undergraduate, Sally Chen, expected to give testimony, will argue that universities need to take race into account to understand someone's experiences - and it's a policy that helps "open the door to all students of colour".

But the case raises bigger questions of what is fair in ultra-competitive university admissions.

Elite universities are not only about academic high achievement.

Seen as a launch pad for careers in business, politics or the professions, they have become gatekeepers for social advancement.

This has put pressure on them to be at the same time both academically exclusive and socially inclusive.

As a result, many university entry systems look at a range of social factors, as well as academic ability.

In the UK, this is often known rather evasively as "contextual admissions". In the US, the most controversial aspect of admissions has often been ethnicity.

Civil rights

Since the civil rights movement in the 1960s, there have been calls for "affirmative action", supporting wider university access for ethnic minority students.

Harvard has always defended its right to consider race as part of an all-round view of candidates.

But this latest claim is not about the type of historical attempts by minorities to stake a claim in white dominated institutions.

Instead, it is a minority group claiming that some applicants are unfairly losing out on places because of the efforts to maintain diversity among other minorities.

This courtroom battle is being seen as part of a wider cultural struggle about race and identity in the US.

While other universities - and some Asian-American campaigners - are lining up to support Harvard, their opponents are protesting with banners supporting President Trump.

All sides will be watching to see if the legal and political ground is moving.

Harvard argues that it has seen off repeated legal challenges to its admissions policy over the decades and that the right to consider an applicant's race has been upheld in successive rulings.

This court case, heard without a jury, is widely expected to have its findings challenged at appeal.

If it comes before the Supreme Court, the balance has shifted and Brett Kavanaugh's appointment could have a further significance for another divisive issue.

More from Global education

The editor of Global education is sean.coughlan@bbc.co.uk