The battle to curb our appetite for concrete

- Published

The world's construction industry is one of the biggest producers of greenhouse gases

We extract billions of tonnes of sand and gravel each year to make concrete for the building industry, and this is having an increasing environmental impact as beaches and river beds are stripped, warn campaigners.

Alongside this environmental damage, the building industry is also a major contributor to greenhouse gases - cement manufacturing alone accounts for 7% of global CO2 emissions.

In many countries, sand is often extracted illegally from beaches or river beds. But once sand is taken from a river, the water flow can become faster and more violent - and the water table alongside a river will fall, affecting farming along the river bank.

Dredging beaches for sand increases coastal communities' vulnerability to storm damage - because sandy beaches act as sponges absorbing a storm's excess energy - something that is increasingly likely because of climate change.

Hurricane Michael earlier this month - sandy beaches can play a key role in absorbing a storm's impact

"The problem is that the demand for sand is outpacing what we know about the environmental impact of extraction," says Dr Aurora Torres of the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Research (iDiv)., external "It is a hidden ecological disaster."

The world's deserts may be awash with sand but this is of no use for construction, because erosion means desert sand grains are too rounded and smooth to be useful. The best kind are the grittier, more angular sand grains found in riverbeds or beaches.

So far our appetite for sand and gravel shows no sign of slowing down. The OECD estimates we use 27 billion tonnes a year, external in construction and that this will double to 55 billion tonnes by 2060.

Loading a truck with sand from a Senegal beach for use in the country's construction industry

Add in the sand and gravel used in land reclamation, coastal developments and roads - and the current annual consumption rises to 40 billion tonnes.

This is twice the yearly amount of sediment carried by the world's rivers. In other words, we're using up sand faster than nature is creating it.

"People are not focused on this because we don't want to know what goes into building a house," says environmental researcher Kiran Pereira, of sandstories.org, external.

Making cement accounts for 7% of global CO2 emissions

Scientists are now working to reduce the amount of raw materials used in the construction industry: switching to more efficient production methods, finding substitutes for cement or sand when making concrete, and boosting the recycling of buildings when they're demolished.

Bath University researchers say up to 10% of sand in concrete can be replaced by plastic, external without significantly affecting concrete's structural integrity - crucial in determining whether to use plastic in concrete for buildings.

"There's a serious issue with plastic waste. Anything we can do to address this and find alternatives to putting plastic in landfill is welcome," says Dr Richard Ball, of Bath University's architecture and civil engineering department.

Concrete can contain up to 10% plastic before it affects its strength significantly, say Bath researchers

In Australia, engineering firm Fibercon, external has developed a technology that uses recycled plastic for reinforcing concrete instead of the traditional steel mesh - this is now being used in footpaths.

Fibercon says by using 100% recycled plastic, the plastic-reinforced concrete gives a 90% reduction in CO2 compared to conventional steel mesh-reinforced concrete.

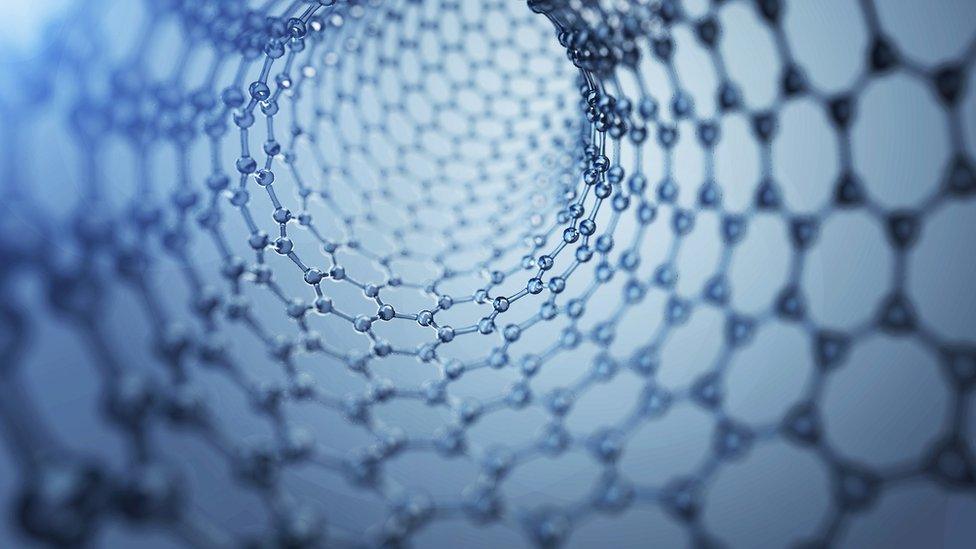

Graphene consists of a single layer of carbon atoms in a hexagonal lattice

At Exeter University, researchers are using nano-engineering technology to add graphene to concrete - making it twice as strong and four times more water-resistant than conventional concrete, external.

This new graphene-reinforced concrete also has huge efficiency savings, cutting the raw materials required to make concrete by some 50%, external.

Circular Economy

The BBC's Circular Economy series highlights the ways we are designing systems to reduce the waste modern society generates, by reusing and repurposing products.

Plastic bottle king: Robert Bezeau says plastic waste can be made into low-cost housing

Another approach that could revolutionise the industry is the 3D printing of houses.

"We could cut up to 40% of the concrete we use, and that would have a huge impact on the sand we are using. There's no penalty for over-design, and so designers and engineers will understandably err on the side of safety," says Dr John Orr of Cambridge University's engineering department - in case those constructing the building are tempted to cut corners.

One way of stopping this could be by 3D printing buildings, creating concrete shapes directly from an architect's design.

3D printing should cut out over-design and mean huge savings in the concrete used in construction

"If you have the drawing sent to the machine you don't need to over-design the building because you get the structure you design," says Prof Sandra Lucas of Eindhoven University in the Netherlands.

Crucially, concrete shapes from a 3D printer are self-supporting. This means they eliminate the metal or wood moulds into which concrete is traditionally poured - additionally saving on raw materials.

Eindhoven plans to become a centre for the 3D printing of concrete structures

Eindhoven is now spearheading what it says is the world's first commercial housing project based on 3D concrete printing, external.

Currently, when buildings and structures are demolished, less than a third of the construction waste is reused, external, according to the World Economic Forum. It argues the construction industry needs to move from a linear "use, then throw away" model, to a circular economy.

"If you design-in the ability to take components apart - to become a catalogue of beams and so forth - you allow for more re-use," says Dr John Orr of Cambridge University's engineering department.

"The apartment blocks, the boring offices that we need for our daily lives - these we need to change how we build and dismantle because we're an economy built on sand and concrete."

The World Economic Forum is among those calling for more re-use of building material

Yet while designing for deconstruction sounds sensible, questions remain.

It may make construction more expensive, and when a building is due for demolition after 40 years or so, those who built it will probably have retired so those taking it down may not know exactly how to dismantle it.

The environmental questions have become more urgent as global cement production has soared - by 300% since 1990, largely due to development in China which accounts for about three-quarters of this - with an accompanying increase in CO2 emissions.

Companies and scientists are now devising ways to capture CO2 in concrete, to soak up more of the CO2 released when cement is manufactured.

CarbonCure's technology can be retro-fitted to existing plants

Canadian firm CarbonCure has developed a way of locking in more carbon by injecting liquefied CO2 into wet concrete.

Not only is the concrete stronger, the firm says it could save up to 700 million tonnes of CO2 emissions a year. So far, 100 producers have adopted the technology.

'Huge impact'

Concrete will naturally reabsorb some atmospheric CO2, but only very slowly. Researchers at France's technology institute, Ifsttar, are looking at ways to speed this up, external, to get recycled concrete to absorb far higher levels of CO2.

"We want to improve the ecological footprint of concrete, and to improve the recycled properties of concrete after demolition," says Dr Assia Djerbi.

Ifsttar hopes its recycled concrete aggregates could help absorb significant levels of CO2

None of the solutions being worked on will, by themselves, solve 21st Century society's appetite for consuming raw materials in vast amounts.

But, says environmentalist Kiran Pereira: "The construction sector as a whole is the largest single consumer of resources - so any kind of change we can make is likely to have a huge impact."

Follow Tim Bowler on twitter: @timbowlerbbc, external