Can we predict when and where a crime will take place?

- Published

Can algorithms really predict where new crimes will take place?

The new crime-fighting weapon of choice for a growing number of police forces around the world isn't a gun, a taser or pepper spray - it's data. But can computer algorithms really help reduce crime?

Imagine a gang of bank robbers arriving at their next heist, only to find an armed response unit already waiting on the corner.

Or picture walking down a dark alley and feeling afraid, then seeing the reassuring blue lights of a police car sent to watch over you.

Now imagine if all of this became possible thanks to mathematics.

Ever since the Philip K Dick novel The Minority Report, which was later turned into a Tom Cruise blockbuster, was published in the 1950s, futurists and philosophers have grappled with the concept of "pre crime".

It's the idea that we can predict when an offence is going to occur and take measures to prevent it.

Now artificial intelligence and machine learning mean this concept has leapt straight from the pages of science fiction into the real world.

Tech firm PredPol - short for predictive policing - claims its data analytics algorithms can improve crime detection by 10-50% in some cities.

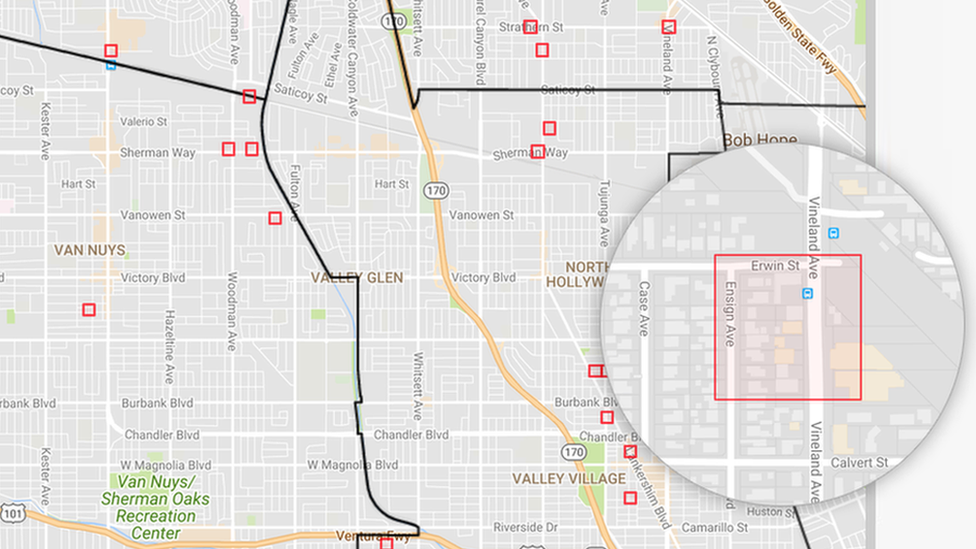

The PredPol software advises police forces on where they should concentrate their patrols

It takes years of historic data, including the type, location and time of crime, and combines this with lots of other socio-economic data, which is then analysed by an algorithm originally designed to forecast earthquake aftershocks.

The software tries to predict where and when specific crimes will occur over the next 12 hours, and the algorithm is updated every day as new data comes in.

"PredPol was inspired by experiments run by the University of California in collaboration with the Los Angeles Police Department," says PredPol co-founder and anthropology professor Jeff Brantingham.

"That study demonstrated that algorithmically driven forecasts could predict twice as much crime and, when used in the field, prevent twice as much crime as existing best practice."

Predictions are displayed on a map using colour-coded boxes, each one representing a 500 sq ft (46 sq m) area. Red boxes are classed as "high risk" and officers are encouraged to spend at least 10% of their time there.

The ultimate aim of predictive analytics is to prevent crime before it happens

Prof Brantingham says machine learning allows PredPol to analyse data, draw conclusions and make connections between large amounts of data that human analysts simply could not cope with.

Sceptics say this is pseudoscience, because crunching crime data to make informed decisions on police deployment is nothing new.

Many forces have traditionally used "hot spot analysis", where past offences are recorded and overlaid onto a map, with officers concentrating on those areas.

But PredPol and others working in this space, such as Palantir, CrimeScan and ShotSpotter Missions, say that traditional hot spot analysis is just reacting to what happened yesterday, not anticipating what will happen tomorrow.

AI and machine learning can spot patterns we've never noticed before.

"Machine learning provides a suite of approaches to identifying statistical patterns in data that are not easily described by standard mathematical models, or are beyond the natural perceptual abilities of the human expert," says Prof Brantingham.

Alexander Babuta, of the National Security and Resilience Studies group at the Royal United Services Institute, agrees, saying: "Retrospective hotspot mapping does not distinguish between two types of 'risky' locations, those that simply experience a high volume of crime over time because they are more attractive to criminals, such as insecure car parks and busy shopping areas, and areas where the likelihood of crime has been temporarily increased due to crime events that have recently occurred.

"But machine learning predictive policing technology does."

Police forces certainly seem to be buying in to the idea.

Data from more surveillance cameras and sensors could improve predictive accuracy

More than 50 police departments across the US use PredPol software, as well as a handful of forces in the UK. Kent Constabulary, for example, says street violence fell by 6% following a four-month trial.

"We found that the model was just incredibly accurate at predicting the times and locations where these crimes were likely to occur," says Steve Clark, deputy chief of Santa Cruz Police Department.

"At that point, we realised we've got something here."

But predictive policing has its critics.

Frederike Kaltheuner, data programme lead at civil rights group Privacy International, wonders whether it will also be used to predict police violence and white collar crime, or simply used against communities that she says are already marginalised.

"We're moving away from innocent until proven guilty towards a world where people are innocent until found suspicious by opaque and proprietary systems that can be difficult, if not impossible, to challenge," she says.

The Los Angeles Police Department has been criticised by civil rights activists worried about its use of predictive policing

There are also concerns about racial and other biases hidden within the datasets. The Los Angeles Police Department, which has been working with Palantir for its predictive policing project, has attracted criticism from local activist groups worried about threats to civil liberties and racial profiling.

Rand Corporation, a policy research institution, has produced a number of studies looking at predictive policing.

Rand analyst John Hollywood says recent advances in analytical techniques have produced only "small, incremental" improvements in crime prediction; results that are 10-25% more accurate than traditional hot spot mapping.

"Current technologies are not much more accurate than traditional methods," he says.

"It is enough to help improve deployment decisions, but is far from the popular hype of a computer telling officers where they can go to pick up criminals in the act."

More data, from surveillance cameras equipped with image and behaviour recognition, and sensors detecting gunshot and intrusion, should help improve the accuracy of predictive techniques, he argues.

Citizens need to decide whether a reduction in crime is worth the potential assault on our civil liberties should such technology be misused or abused by those in power.

Follow Technology of Business editor Matthew Wall on Twitter, external and Facebook, external