Why robots will build the cities of the future

- Published

Robots on building sites could become common as firms look to replace their ageing workforces

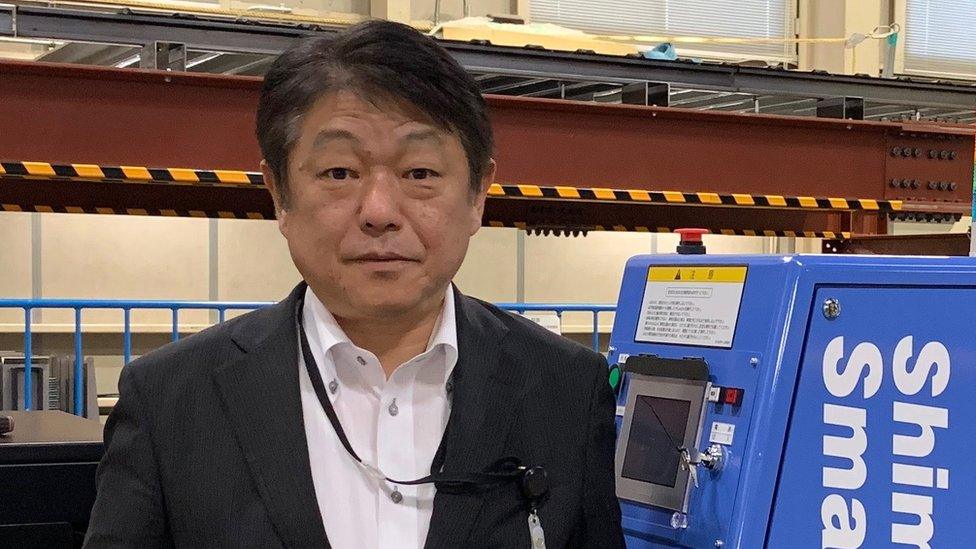

Shinichi Sakamoto is 57, and works for Shimizu, one of Japan's biggest construction companies. He is part of a greying, and dwindling, workforce.

"The thing is, statistics show a third of [Japanese construction] labourers are over 54 years old, and they are considering retiring so soon," says Mr Sakamoto, who is deputy head of Shimizu's production technology division.

And they're not being replaced by younger builders. "The number of labourers under 30 is just above 10%," he says.

In September, Mr Sakamoto's firm gained a promising new co-worker - a robot.

Robo-Carrier is currently working on a high-rise development in Osaka, transports heavy gypsum board pallets nightly from the ground floor to where they're needed.

Japan faces a national shortage of building workers, says Shimizu's Shinichi Sakamoto

"Can you imagine that materials are in the right position in the morning when labourers come to the site?" says Mr Sakamoto. "He even works at night time."

Robotics is one area poised to benefit from coming superfast 5G mobile networks. Better connectivity will make it easier for multiple robots to co-operate.

Many small robots could "swarm", working together on different parts of a task. An example is the collaborating 3D printing robots being developed at Singapore's Nanyang Technological University, external - each of which can print concrete following a computer map.

All robots in a "swarm" could learn from what one robot is learning.

Collaborating robots can be more efficient than just one - they can tackle different parts of a job simultaneously

Shimizu is introducing other robotic workers, external too.

Robo-Welder welds steel columns, while Robo-Buddy, inserts hanger bolts and installs ceiling boards.

The robots operate autonomously, performing tasks a supervisor assigns them on a tablet.

Robo-Carrier can recognise and avoid obstacles, while Robo-Welder uses laser shape measurement to determine the contours of the object it is welding.

"There must be more and more robots on site," says Mr Sakamoto. "Labour shortage is our nationwide problem."

Japan's construction labour pool will fall to 2.2 million by 2025, down from 3.4 million in 2014, Shimizu says.

The market for construction robots is set to double to $420m by 2025

And this is not just an issue for Japan. Worldwide, too, the construction business is looking increasingly to robots as it confronts a shrinking and ageing workforce.

Globally, the construction robot market will more than double in size to $420m by 2025, external, up from $200m in 2017, say consultants QY Research.

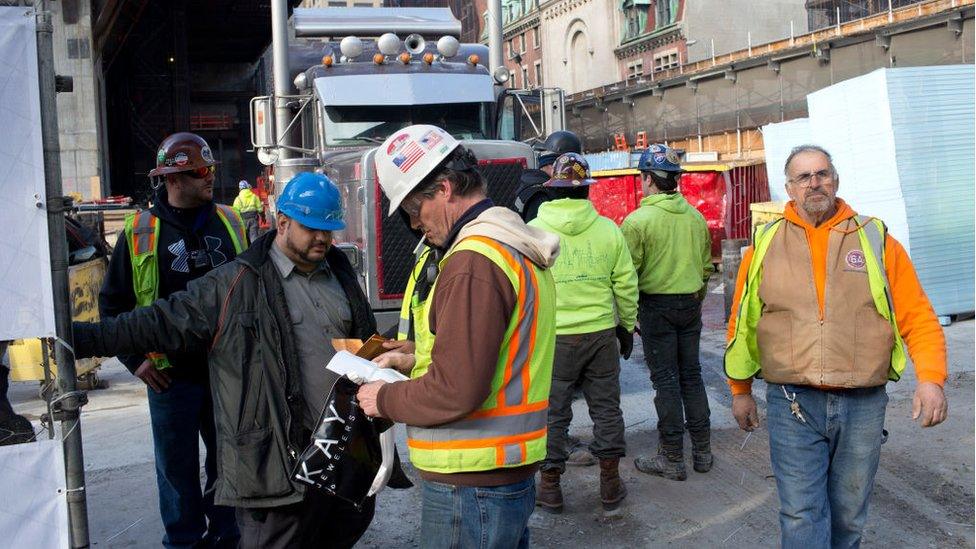

In the US, construction workers are also getting older. The average age is currently 43, says Jeremy Searock, co-founder of Pittsburgh firm, Advanced Construction Robotics.

A decade ago, the average age was mid-thirties.

And 80% of US general contractors say they are having trouble filling vacancies for skilled workers, according to a survey in August.

The average age of US construction workers is now 43, almost 10 years higher than it was a decade ago

There's a "clear trend", says Mr Searock, "the younger generations are not going into the construction fields."

This is why Shimizu has invested 20 billion yen (£140m; $179m) since 2015 developing construction robots, says spokesman Hideo Imamura. Its robots reduce manpower needs for a given task by 70% to 80%, he says.

In the US, nearly half of construction jobs could be replaced by robots by 2057, say researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign and Midwest Economic Policy Institute.

As well as been tireless, robots can do the toughest, most dangerous jobs on a building site, says Mr Sakamoto, potentially preventing injury and loss of life.

"Work which suits robots is for robots, and work which suits humans is for humans," he explains.

TyBot has been developed speed up the tying together of rebars, or reinforcing steel bars, in concrete structures

In future, faster data speeds thanks to 5G, combined with lower latency - the time gap between a request and a response - means robots will be able to put more processing tasks into the cloud.

The end result is a cheaper, cleverer robot.

Shimizu currently controls its robots using 4G mobile and wi-fi, which means that when they work on buildings over 200m high, they have to extend the wi-fi network area using relays.

5G would free them from this dependence, says the firm.

Robots could then carry out hazardous or repetitive tasks on remote sites without the need for installing a wi-fi base station - providing, of course, that the 5G network stretches that far.

One advantage of construction robots is that they can work through the night

One of hardest bits of building bridges is tying together rebars - the reinforcing steel bars that add tensile strength to the concrete.

"Bent over, in hot sun on a bridge, with your hands manually tying this stuff" is tough work, says Mr Searock.

There could be hundreds of thousands or even millions of intersections to tie.

And in north-eastern United States, he says there is a "pronounced labour shortage" for this work, accentuated by its seasonal nature.

So last year, Advanced Construction Robotics developed a robot - TyBot - to do this job, working on the Freedom Road bridge in Beaver County, Pennsylvania.

It tied 24,000 rebar intersections at a rate of 5.5 seconds for each one. The fifth TyBot is coming off the assembly line now, Mr Searock says.

This robot can lay 380 bricks an hour, which is six times faster than a human bricklayer

Meanwhile, Tokyo's National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology has built a prototype robot, called HRP-5P, which can install plasterboard partitions.

And New York company, Construction Robotics, recently built a semi-automated bricklayer or mason - SAM for short - which laid 250,000 bricks for the Poff Federal Building in Roanoke, Virginia.

Laying 380 bricks an hour, it is six times faster than a human bricklayer, its makers say.

Building workers in the US with robots designed to lift and place heavy materials on construction sites

The global construction industry has lagged behind other sectors when it comes to technology investment, largely because it is "notoriously fragmented", says Will Hughes, a construction management and economics professor at the Reading University.

This splintered nature means many small businesses are "dependent on the status quo", so "working practices date back to Victorian times", he says.

But crippling labour shortages mean that the first construction companies to put robots to work effectively will have a significant advantage, he argues.

So don't fret if in a few years you open your door and see a Dalek.

It may be there to convert your loft.