Mexico 1971: When women's football hit the big time

- Published

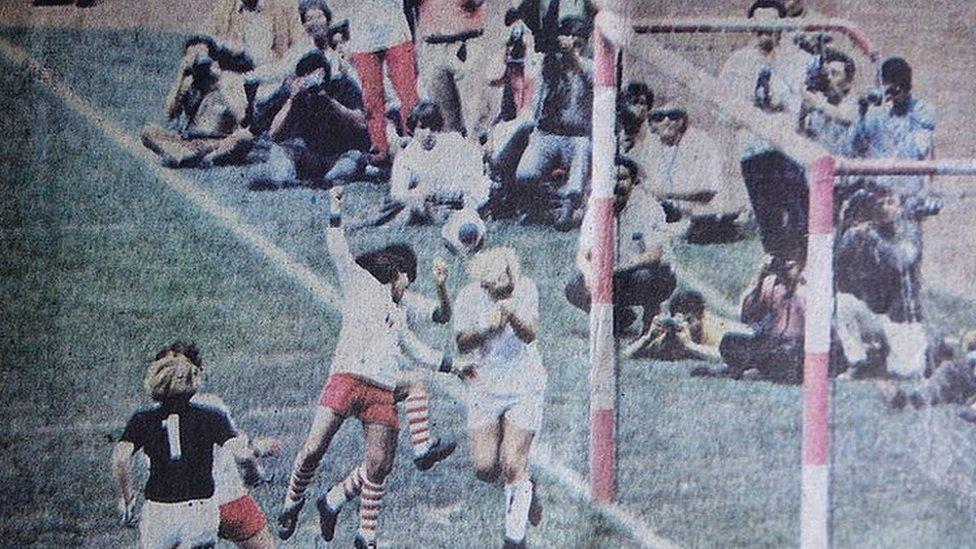

Action from the 1971 women's final between Mexico and Denmark in front of 110,000 fans

It was short lived.... but for three memorable weeks in the summer of 1971 women's football flared brightly like a comet, before crashing back down to earth again.

Just 14 months after Brazil had crushed Italy in the 1970 men's final in Mexico City, football fever was once again sweeping the host nation, but this time for an unofficial women's World Cup.

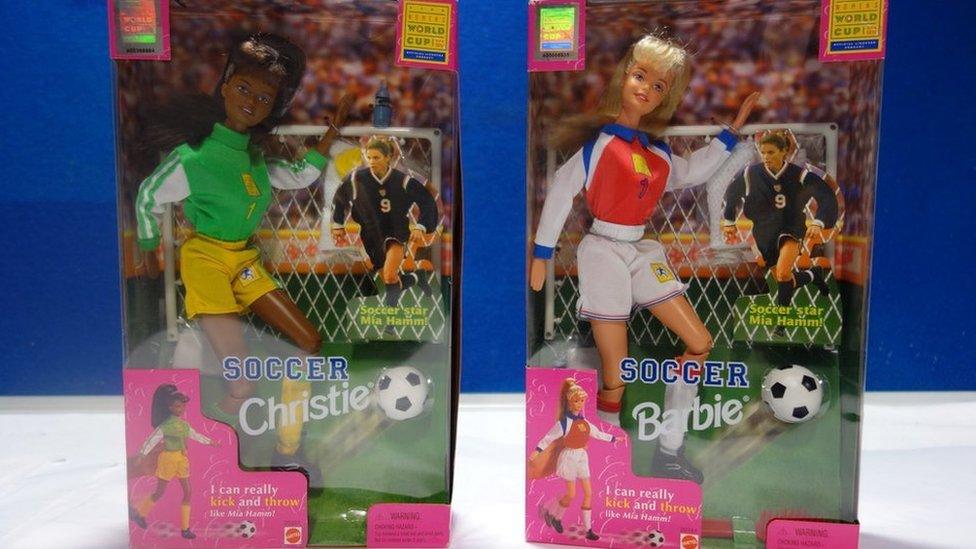

And it wasn't just fans who were caught up in the excitement - big brands, TV broadcasters and merchandisers of all types also wanted a piece of the action, as women's football briefly became a commercial product to rival the men's game.

Now, with the 2019 Women's World Cup draw on Saturday, the tournament is big business - and one backed by 11 major brands, but such a commercial approach was new ground back in 1971.

'Different world'

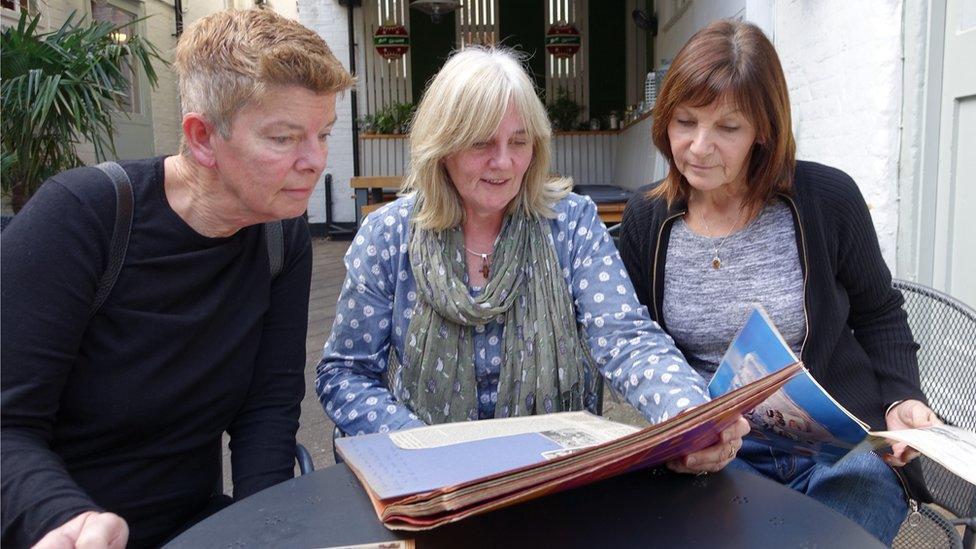

"It was like going into the Tardis or to Narnia - being transported to a different world," recalls England's left midfielder Chris Lockwood, then 15 and now 62.

England players (l-r) Chris Lockwood, Leah Caleb and Gill Sayell reminisce about Mexico 1971

"I don't think we knew what to expect. We had only played in the small qualifying tournament in Sicily, which was played on the park-type pitches we were used to.

"And suddenly we were in the middle of World Cup fever in this huge glitzy, professionally staged, global tournament."

The England team training in Mexico

The six-team tournament was sponsored by Italian drinks giant Martini & Rossi, and other backers included Mexican beer brand Carta Blanca, slimming soft drink Dietafiel, and national tea brand Lagg's.

A plethora of alcoholic, electronics and other products were emblazoned around the capital's Azteca Stadium.

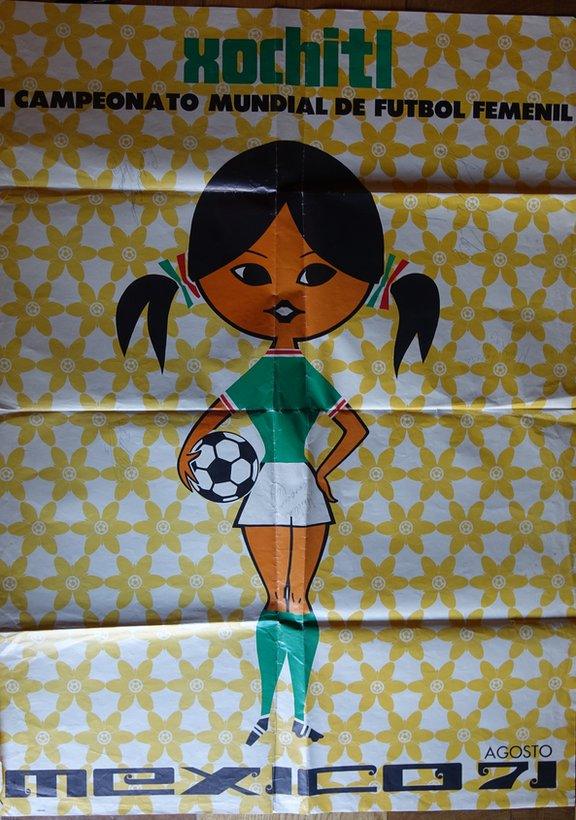

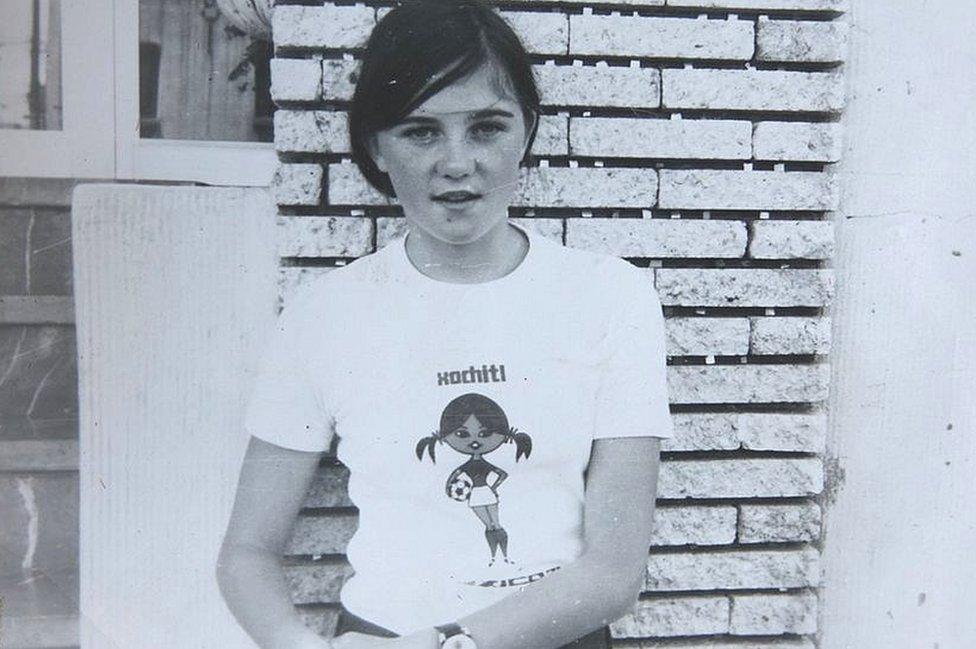

Pin badges, t-shirts, bags, dolls, magazine and programmes were produced for sale, with many of the items featuring tournament mascot Xochitl, a young girl in football kit.

The image of Xochitl was used to sell everything from keyrings to posters

Meanwhile, sales of tickets, priced from 30 pesos (£1.15) to 80 pesos (£3), exceeded expectations, with the largest crowd to attend a women's football match registered in this tournament.

An estimated 110,000 fans attended the Mexico v Denmark final while some 80,000 watched Mexico v England. The other stadium used for the event was in Guadalajara.

Piggybacking on Mexico '70

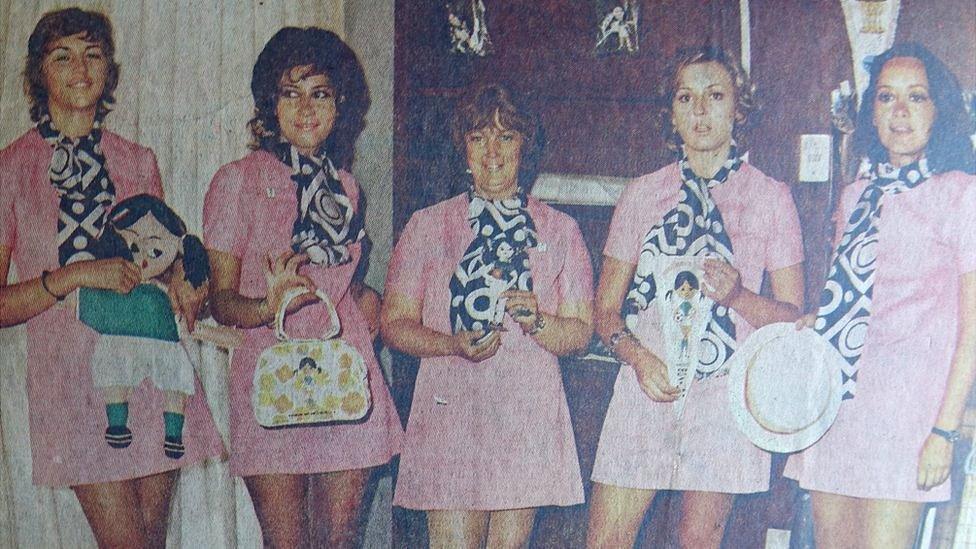

To make the event appeal to a female and family audience, stadium goalposts were adorned with painted pink hoops, and tournament staff, including team translators, were kitted out in distinctive pink outfits.

A local paper records action from the Mexico v England game in the 1971 World Cup

Prof Jean Williams is academic lead for the Hidden Histories of Women's Football project at the National Football Museum.

"Mexico '71 was a success because the organisers did not assume it would be a commercial or sporting failure. It was sold and promoted as a football tournament, one that just happened to feature women.

"They also assumed that they would get healthy crowds in the two stadiums, which had been used in the men's World Cup the year before."

The 1971 translators, with tournament merchandising (pictured in a 1971 Mexican paper)

She says key to the commercial success was the use of mascot Xochitl to sell merchandising, plus the use of a powerful PR team to garner TV and press coverage.

'Huge backup for England players'

Lioness Lucy Bronze, 27, is a Champions League winner with Olympique Lyonnais, and says current England players owe a debt to the 1971 team "and all the women's players who came before us".

"I never even thought it could be a job. I just liked playing with my big brother. The dream was always just to play football, but I didn't know you could make it a major part of your life," she says.

"Later I was concentrating on getting my degree, and maybe playing part-time football as well as for a little bit of money, not as a career. But as the Women's Super League got bigger every year the opportunities arose for me," says the ex-Sunderland, Everton, Liverpool, and Man City star.

She says in contrast to 1971 there is a huge backup team for the players, as big as the 23-strong playing squad, including media personnel, physios, dieticians, sports scientists, sleep experts, coaches, kitmen, security guards and drivers.

The players are also given regular media training. "That could include things like what language to use on social media," says Bronze. "We also have commitments to our sponsors like Nike and Head & Shoulders."

'Ridiculous'

Back in 1971 the British media was comparing England's young star, 13-year-old right midfielder Leah Caleb, to Manchester United's George Best as the team jetted out to Mexico.

England player Leah Caleb, aged 13 in 1971, sporting a Xochitl mascot t-shirt

Caleb, now 60 and recently retired after a career in the NHS, recalls: "By taking part in the event we jolted the FA. We were banned from playing for taking part in an unofficial World Cup.

"But they realised very quickly they were being ridiculous and our bans were lifted."

Indeed, it could be argued the team's participation played its part in the FA eventually lifting its wider 50-year ban on women's football that same year.

Time-and-motion man

The FA's hidebound approach was in stark contrast to the forward-thinking figure behind the 1971 England team, Harry Batt, secretary of the Chiltern Valley women's club, which made up the majority of the England side.

Football visionaries: Harry Batt and his wife June with members of the Chiltern Valley women's club

An intriguing figure, Batt was a factory time-and-motion man in Luton who could speak a number of languages, and had a vision for women's football where the game would be commercialised and players paid for their efforts.

"I am certain that in the future there will be full-time professional ladies' teams in this country, and we are hoping to be one of the first," he said in 1971.

A 1971 tournament pennant featuring the six teams

He believed England could emulate Italy, where he had taken a team in 1970 for the first unofficial women's World Cup, and where women played before 30,000-strong crowds.

But, like the 1971 World Cup event itself, he would be a couple of decades ahead of his time. He suffered in being ostracised by the FA, and his club team - which was trained by his wife June - folded.

Extra week

For event backers Martini & Rossi it was an opportunity to build on the stadium advertising they had done in Mexico during the 1970 World Cup.

The Italian drinks giant paid the expenses of each of the 1971 teams, including flights, hotels and playing kit.

Martini advertising can be seen as Pele scores in the 1970 men's World Cup final

"It was an opportunity for them to promote their brand name," says England's right winger Gill Sayell, now 62 but then aged 14.

"They also provided the large gold cup the teams played for, and paid for the England team to stay on for an extra week after we were knocked out."

'Brutal'

Lockwood, Caleb, Sayell and their team-mates were not provided with any payment - official or unofficial - for their efforts in Mexico, though they were given a reception at the British embassy.

Unfortunately for England they lost their three games, 4-1 to Argentina, 4-0 to Mexico, and 3-2 to France. In the final Denmark defeated the host nation to add to their victory from the previous year in the unofficial 1970 World Cup.

"Our game against Argentina was brutal, and two England players ended up in plaster casts," recalls Caleb.

"But we wouldn't have changed our experience for anything. As well as the chance to play on the same pitch as Pele, the Mexican people - many of whom had very little - really embraced us."

- Attribution

- Published26 October 2018

- Published6 March 2018