Davos 2019: How dining in the dark can open your eyes

- Published

At the "Dining in the Dark" event there weren't even candles

Putting both your hands on someone's shoulders a few minutes after you've just met, feels strange, a little too intimate.

But at the "Dining in the Dark" experience at Davos, we have no choice. We have to hold on to our waiter, Darren, so that he can guide us into the room. If we weren't physically touching something, it would be easy to trip over.

This event is the hot ticket in Davos this year, with just 50 spaces each night for a conference with 3,000 attendees.

Gina Badenoch, the founder of social enterprise Capaxia, and the organiser of this event, hopes the experience will encourage guests to broaden the type of people they employ. She says it is not about blindness as such, but about making us aware of how often we judge people solely on their appearance.

At a similar event in Mexico 12 years ago, Ms Badenoch experienced walking down a street in the dark. She was so moved by how it made her feel she decided she would focus her career on changing perceptions of visually impaired people. She is a photographer, and she decided she would teach photography to people who couldn't see. She knows it sounds "crazy" but it is possible, she says, using sound to locate a subject before taking a picture.

Finger food

This evening she wants to give us that same experience: doing without the visual cues we usually rely on, to make us better listeners. "It's about creating awareness of people's potential," she says.

It's a good lesson in the context of the frenzied networking event that is the World Economic Forum gathering at Davos. Name badges may ostensibly be about security, but they're also used to judge at a glance whether the person in front of you is worth talking to.

Stripped of our mobile phones and even our watches, we're led down a slope into the pitch black. There's no chink of light whatsoever. It's uncomfortable and disorientating.

Gina Badenoch wants us to share the experience of relying on our other senses

Our table of six is totally reliant on Darren, who guides our hands to our plates and tells us where to find cutlery, glasses and bread.

In the dark, it's initially hard to make sense of what people are saying. But then it becomes oddly relaxing. Several of us end up closing our eyes to avoid straining to see. I am struggling to use my knife and fork, so I resort to using my fingers for the salad starter, and even the couscous and chicken main dish. After all, no-one will know.

Beforehand, conversation had remained politely reserved, but in the dark my fellow diners and I opened up, about our relationships, love affairs and break-ups. One guest went so far as to share his conviction that you knew you were with the right woman when you were comfortable farting in front of each other.

Ashamed

Eventually, after two hours, the lights go up and we see our waiters for the first time - who it transpires are all themselves visually impaired. It's an emotional moment.

Our waiter Darren who had seemed so powerful in the dark as he ably guided us, is holding a stick.

If any of our table had met him beforehand, we agree we would have assumed he wasn't anywhere near as capable and would have judged him accordingly. We all feel ashamed.

The highly capable waiting staff were all visually impaired

That moment is what Ms Badenoch hopes we will remember. She has organised similar dinners where the waiters are young and unemployed, and ones with people in wheelchairs. This year, she plans to run some with refugees and immigrants.

"See them for what they can do, not what they can't do," is her mantra.

Furious

Unconscious prejudice, particularly against disabled people, is a big theme at this year's Davos conference.

In the UK, almost a fifth of the working age population is disabled, according to the latest officially statistics. Globally around 470 million disabled people are of working age, yet they are far less likely, external than their able-bodied peers to be working.

These figures make Irish entrepreneur Caroline Casey furious.

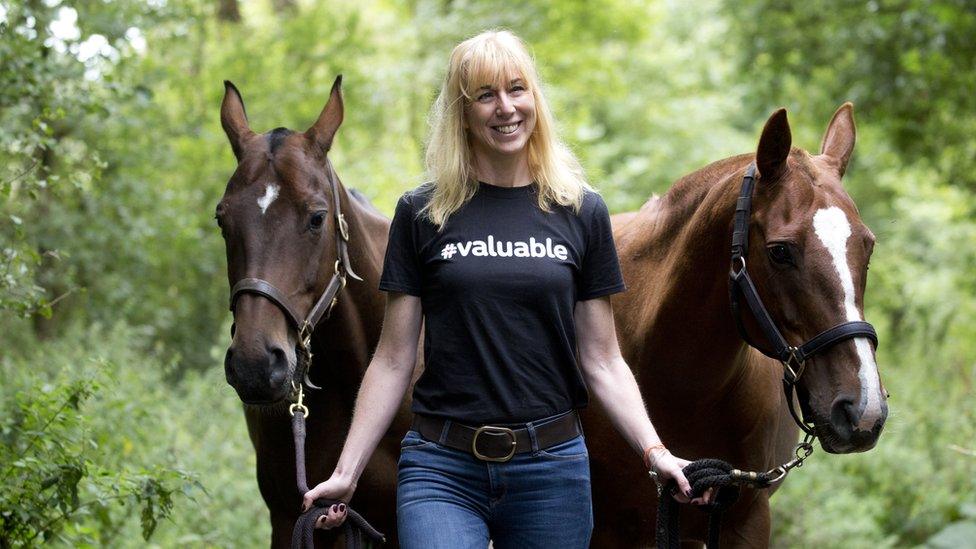

The founder of business inclusion firm Binc, she is at Davos to launch the next step of her "Valuable" campaign, aimed at getting 500 firms globally to put tackling disability on their board agenda within the next year.

Ms Casey, the adventurous type, launched the campaign in 2017 with a 1,000-km horse ride across Colombia.

She is driven in part because she too has a disability. Born with ocular albinism, a genetic condition that primarily affects the eyes, she hid it until she was 28. She had assumed that everyone's sight was as bad as hers until at 17 she told she wasn't allowed to drive. Later her sight became so bad she couldn't hide it any longer and "came out". Now, at 47 she doesn't want anyone to feel like she did.

"I don't understand why we can't accept the full human experience, we're all unique," she says.

Awkwardness

Jeff Dodds, managing director at Virgin Media, says it's not necessarily prejudice, but awkwardness holding firms back from being more inclusive.

He says managers often worry about saying or doing the wrong thing.

Caroline Casey rode across Colombia to publicise her cause

The telecoms firm is partnering with Binc on the "Valuable" campaign, and has committed to helping one million disabled people to find and stay in work by the end of next year.

He says firms, particularly customer-facing ones like Virgin Media, can't afford to ignore such a large part of the population.

"The more inclusive we are, and the more different people we have in the organisation, the better our services will be," he says.

He says injuring his back two years ago taught him how hard it was for people with additional workplace needs to have that conversation with their managers, but how failing to speak up meant you might not get the support you needed.

Two hours eating dinner in the dark may not give you quite the same level of insight into how physical impairment can feel. But it may go some way, Ms Badenoch hopes, in helping us understand that vulnerability.

- Published23 January 2019

- Published22 January 2019

- Published23 January 2019

- Published23 January 2019

- Published22 January 2019